|

There are usual, everyday, fortuitous, and familiar narratives, like the family portraits that line the walls of our homes (which we often do not even notice). And there are risky, visionary stories that do not fear crossing borders or following absolutely dangerous paths, which are unviable from the point of view of what is accepted by rationality. In this second case, we undoubtedly find Karim Ghahwagi and his strange travel books Amerika and Europa, systematic descriptions of the new continents of madness. In the continental amplitude of the fantastic narratives, 'Weird', Karim's fictions occupy an original place, between political satire and surrealistic fantasy, between decaying perception and the dynamic record of travels and displacements, between myth and carnival. The author kindly collaborated with the interview we proposed – a first, broader and more systematic part, in writing, accompanied by the second part, intuitive, on video. The two interviews follows below, and I hope both are useful to illuminate the intricate visions of Karim within his multi-layered perspective. Interview with Karim Ghahwagi (Video Version) Interview with Karim Ghahwagi (Written Version)

1) The universe of Amerika and Europa novels have a clear resonance of certain works of authors such as Mikhail Bulgakov, William Blake, Emanuel Swedenborg or John Milton (authors, incidentally, cited in these two novels). But there is an evident, very personal development in an absurd, surrealistic and satirical direction which, in addition to revealing a very peculiar verve, also indicates other influences. How did the process of creating these two works take place? What are your main references besides the authors mentioned above? I first encountered Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita while working on my undergraduate literature degree at Bard College in Upstate New York. I was completely derailed by that astonishing book, and ended up writing my literature dissertation on it. I had the great fortune of attending a wonderful class studying Kafka and Bruno Schulz with author Norman Manea, and I was always very interested in the works of the fantastic, the role of the exiled writer, the processes of estrangement, the idea of the writer living far away from his home country. Something that I also encountered in an amazing class reading African short stories with Chinua Achebe. It was however in a class on the literary fantastic, that my professor Lindsay Watton, to whom I dedicated my first published work Amerika, introduced me to Mikhail Bulgakov and Nikolai Gogol. The Master and Margarita completely changed everything for me, but it also encompassed a number of my own preoccupations, and it is certainly a magnificent example of the great polyphonic novel, and the manner in which, as Mikhail Bakhtin writes, it also exemplifies the effects and processes of the carnivalization of literature. These ideas where very important to me, particularly for both Amerika and later, Europa. The carnival could be understood as a celebratory, subversive form of resistance against the absurdity of authoritarian regimes, the idea that laughter and chaos, instigate transformation, remove the tired, malevolent divisions in society, a source of freedom against oppression. William Blake too was against all forms of both social and spiritual repression, and we know that he had an altercation with a drunken soldier in the back garden of his own home and was deeply affected by being falsely accused of sedition; and Mikhail Bulgakov lived through the dark period of Moscow in the 1930’s and forever it seemed, was in Stalin’s shadow (and had personally received a phone call in his home from the man Himself, who can forget). He too never lived to see his great novel published in his lifetime. Both artists in a way were exiled or outsiders, who would only gain increasing recognition after their deaths- though Bulgakov had some success in the theater. In response to your question concerning John Milton, Bulgakov would often refer to his novel in progress as ‘a book about the Devil.’ Certainly Goethe’s Faust was a huge influence, and John Milton’s Satan is very much an anti- hero who never-the-less spurs revolutionary action, an instigator and instrument for change. Woland and his infernal retinue in The Master and Margarita represent those chaotic, whimsical destabilizing forces, demons and clowns, with infernal fractured gazes, causing great de-hierarchizing effects, often confronting and ridiculing and exposing oppressive, unimaginative forces. It is not without reason there is an early central decapitation scene in Bulgakov’s novel, and Blake too was very much affected by the forces of the French Revolution, and how those fires of change swept through Europe and America. In a sense, going back to William Blake, some would identify the beginning of the Romantic period in England all the way back to Blake, a transition, a movement spurred from Goethe to Blake. Literally Katerina Goethe in the beginning of Europa is bringing this revolutionary idea from continental Europe to Albion, as there is a relationship between the sweeping revolutions in America and Europe that Blake was moved by. The idea of confronting the rational, the mathematical, the militaristic, and delving into that deep, internal, mystical well, to put poetry and mysticism, and the whole world in relation to the human. Blake is a true profound mystical humanist. Finally to answer the question of how both Amerika and Europa came to be and their influences. Initially Amerika was submitted as a novelette because Dan Ghetu of Ex Occidente Press had an open call for submissions for an anthology in homage to Mikhail Bulgakov. That ended up becoming its own book, and it was incredibly and lovingly designed by Dan Ghetu. I felt very fortunate to have that work so lavishly presented. In a sort of meta-fictional book about books, where the nature of books themselves are disappearing, or stubbornly reluctant to disappear, it was not without a great amount of joy to seeAmerika published that way. While I had entertained the thought over the years to write a sequel to Amerika, it would be just as comically ludicrous I reckoned, as Mr. Sweden’s supposed sequel to The Master and Margarita as depicted in Amerika. Then when Damian Murphy and Dan Ghetu invited me to submit a short story intended as a panegyric for William Blake, I couldn’t resist drawing parallels both between Mr. Sweden, the Travel Writer in Amerika, and Swedenborg’s effect on William Blake, particularly on The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and his two canonical works, America and Europa. So all this devilry is really Damian Murphy and Dan Ghetu’s fault, for which I am eternally grateful! The thought entertained me to no end however, and what I had intended to be a similar novelette (or novelarette- a term coined by D.F.Lewis), just continued to grow into the short novel that became Europa. I always knew that György Ligeti's opera Le Grand Macabre would inevitably have to figure in the story and was certainly an influence on Europa. All kinds of music and sounds are important to the worlds of both books. The Master and Margarita is an incredibly sonorous and cacophonous novel. I think that the extraordinary work of Brian Evenson had an influence on Amerika, too. I had spent two years adapting The Brotherhood of Mutilation, originally published by Paul Miller’s wonderful Press, Earthling Publications- which is the first half of the astonishing novel Last Days- into a screenplay. Working quite a bit with the dialogue and the world of Last Days had an effect in certain ways in which the Jensens for example, spoke inAmerika, and the manifestation of pitch black comedy in a detective noir setting. Brian Evenson creates an unsettling feeling in his stories that is all but impossible to pin down, and it is completely unique and powerful. His extreme care and awareness of certain rhythms in language, coupled with the profound existential preoccupations and often blackly comic subject matter in these highly compressed, terrifying narratives is really like nothing else I have ever encountered, and utterly astonishing. Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil, and Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comic books, and the work of Clive Barker are certainly all influences too. And I think I have always been amazed by Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy of novellas- particularly the manner in which the detective-writer is confronted with subversive existential and inter-textual conundrums. The extraordinary bodies of work of Ramsey Campbell, Peter Straub, China Mieville, J.G.Ballard and Michael Marshall Smith are certainly all influences. What motivated me to write Amerika was particularly the political realities in Scandinavia and the US after 9-11. The vilification of foreigners and immigrants by right wing elements, the shrill tone of some newspapers in the following years, the constant attacks on the Scandinavian welfare system by greedy and nihilistic corporatist forces. In Europa, I think the absurd rise of Donald Trump, the malevolent, racist rhetoric against the poor, the environment, the huge masses of refugees displaced around the world, the detention centers, the ugly rise of elements of authoritarianism in Europe and America in our present time. 2) There is an extraordinary emphasis in Amerika: the manuscript from an unsolicited (or perhaps impossible) novel that does not burn. It reminded me of certain images of the Renaissance/Baroque era, with the same theme – the book that resists the fire because of the heretical content in its pages. At the same time, this emphasis is associated with the theme of the clandestine manuscript tradition in the Eastern Europe, the concept/ strategy of the samizdat. To compose this moment in your book, what references do you use? How did you imagine this impossible object? The Master and Margarita remained unpublished during Mikhail Bulgkov’s lifetime. He burned an early version of the manuscript fearing persecution for his work. ‘Manuscripts don’t burn’ is much quoted from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel. After the book was burned the first time, he would then go on and work on the novel for the rest of his life until his death in 1940. This quote is a testament to the immortality of ideas, that they will overcome censorship, that ultimately suppression will fail. It is also a statement filled with some irony, for the function of infernal fire in the novel also has particular significance, as does a certain subversive Manichaean world view. The Master does not seek ‘light’ in the novel, he seeks ‘peace’. So there are certain layered complexities and ironies in this much quoted statement. I also found Alcediades, a wonderful and complex relationship to light, and fire and illumination in your excellent collection Lanterns of the Old Night. This collection is filled with illuminating glows, from the moon and magic lanterns, and midnight fires on darkened beaches, and in dreams with vast architectures. Even the process of illumination itself, to reveal, and to literally illustrate a text, has a complicated relationship with that ancient light and fire, reaching all the way back to the Platonic cave of ideas, of light and shadow and reflection... So I think both light and fire, and the meanings of ‘infernal fire’ is a complex one, in both its destructive and Promethian dimensions. After Bulgakov burned an earlier version of the manuscript of the Master and Margarita, he ended up rewriting everything from memory, and it was not uncommon for authors at the time to memorize their work in case they were completely destroyed, or for fear of persecution. The Master and Margarita remained unpublished for decades after Bulgakov’s death and finally appeared in censored form in 1966. I don’t believe that a complete uncensored version appeared in English translation until the late eighties. In totalitarian regimes, ideas that deviate from the political program are obviously deemed taboo, and those images of Nazi book burnings are impossible to forget. In Amerika I like the idea of the book as a fantastical object, that it has a power to not only to shift perspectives, perceptions and thinking, but to also literally, to shift architectures, to transform the very fabric of reality, to open doorways to new experiences and vistas. To have characters literally jump off the page, or to interact with each other from different periods and different universes, is something that gives me much enjoyment, and becomes an exercise to test and see those said works when they are given new vistas and new perspectives in the way they are rearranged. Ultimately they are celebrated. 3) Still about the manuscript impossible to burn: the subject of indestructibility appears in his two books through rather complex approaches. Both the manuscript in Amerika and the bullet-proof mannequin in Europa embody strange drives that are impossible to control or liquidate. What would be the origin of this theme obsessively reimagined in your narratives? Working in the shadow of Nazism, Hans Bellmer created these highly unsettling mannequins, pre-pubescent girls with contorted, disfigured anatomies as a way of addressing the grotesqueries and the destruction of innocence by Nazism. These highly unsettling images were impossible to forget when I first encountered them. I am also fond of the Brothers Quay’s vast, incredible body of stop motion work, and their interpretation particularly, of Bruno Schulz’sThe Street of Crocodiles, which is one of the masterpieces of stop motion cinema, or any cinema, for that matter. There is a tradition that the Brothers Quay- in being successors to the work of Jan Svankmajer- that also in my mind, reaches back to a cinematic and literary tradition of the fantastic in Eastern Europe. The idea of the cinema imbuing inanimate objects with life and animation. There is this interesting transition from the literary fantastic to the cinematic one in this particular, vacuum-like, but highly charged and mystically electrical, stop motion space. In fact in later work, where the Brother’s Quay work with ‘real actors’, the human characters in many instances almost appear to be like mannequins of flesh, directed in these strange austere, fetishized spaces- obsessed with structure and discipline, while seemingly struggling to contain vast inner emotional landscapes. I kind of wanted to play with that, and also have the mannequin take on some of the facsimilied characteristics, or lack thereof, that we encounter in the repetitive, militaristic machine-like, banal consistency of military dictatorships. I also think that individual human beings are reduced to mere numbers in malevolent bureaucracies, and are obviously made to be large, unidentifiable masses, and not treated as individual human beings. I also wanted the mythic fires of Blake’s Golgonooza to spread as kind of infernal, destabilizing carnival-march, an oxymoron perhaps, of mannequins. However these mannequins have momentary notable differences in gender, and they are not always completely indestructible, and do suffer from the wounds of both war and time. It was also important I guess, to have the Supreme Chancellor very much surrounded by a puppet cabinet, quickly exchanged, quickly discarded wax mannequins. I had a whole scene of a puppet show trial in the novel that I removed before publication. These so-called indestructible texts, imbued perhaps with a kind of supernatural resilience, are often then, created by extremely vulnerable individuals, writers surrounded by violence, war, oppression etc. I think there is a relationship there, the idea of a very vulnerable vessel being able to access some power or ability, through the fire of invention, to create something ethereal and powerful, divorced, but intimately still, a profound part of themselves. The text being a document, literally of an indestructible mythic voice of fire. 4) The disappearance of America is one of the central leitmotifs of both Amerika and Europa. It is evident that the allegorical burden of this conception goes beyond the more obvious dimensions. In that sense, you could comment on the origin, development and political and aesthetic sense of this idea of the disappearance of an entire country, and the importance of such a conception in your plots. I think the fantastic often operates in that twilight space, in a moment of transition between light and darkness, where our perception of things become uncertain. Having then, something missing altogether from a reality we are usually familiar with, also operates and creates interesting spaces to explore. Sometimes a mere inversion of things can profoundly shift our understanding of things and form fresh perspectives. Sometimes creating those absurd inversions, from situations that are already absurd, well, both farce and satire inevitably arises, sometimes in a necessarily rather shrill and unpleasant dimension. I think travel is its own country. There is a particular space that you occupy when you are in transition, or know that your time in a particular new space might be finite. I think the manner in which your mind operates might in part, be quite particular to that experience as well. I feel very fortunate to have benefited from the marriage of cultures that have made up my immediate family life and from having lived on three different continents. I think my life has been enriched by the immersion into other cultures in my private, social and professional life. I am grateful for gaining a wider perspective into other cultures and trying to understand better what makes us all human beings, while respecting the deep, historical roots that make cultures unique and wonderfully idiosyncratic. One side to this however, is also identifying which is really your home, where you feel that you are least a stranger- or why you feel particularly, that a particular place is your home. Writing and thinking in different languages I think also affects your thought processes. While I don’t do any translation myself, you do hear from writers that also translate books from other languages, and how the process of translation helps them with their own writing, with how they construct sentences and meaning in their own native tongue. Perhaps then, to attempt to answer your question, a marriage of some of these preoccupations I think form part of the background I guess. I am also suspect of those forces then, that try and separate us from each other, or that absurdly suggest that one group of people from a particular culture is inferior to another, and the great, just as absurd lengths they go to, to forward that agenda. 5) It seems to me that in Europa there is a strong influence of William Blake, of the visions and perplexities and even of the influences of that author, adapted to your style. Has the Blakean universe, in this context, come as a reasonable option because William Blake himself created very complex mythology involving continents, territories, countries? What is the relation of the Blakean visions and of this perception of totalitarian politics in his book? Blake has created a complex mythology, one that develops throughout his life, and was continuing to do so until his death. While Blake loved his homeland, and even envisioned a new sort of central spiritual nexus in England, his Albion, his new city Golgonooza, he was very much au courant with the political and social situations in his country and in the wider world. He was fascinated with the swell and power of ideas traveling across vast distances, literally revolutionary ideas moving on the great currents of history. He may have been disillusioned by some of those outcomes, but he was certainly acutely aware of them, and was moved to address them in his work. Blake is constantly working also with a kind of psychogeography, juxtaposing continents atop of one another, sometimes encompassing the totality of the exterior cosmos inside the body of every human being. It’s a remarkable, sophisticated and humane and mystical gesture. That this is in opposition to banal, totalitarian, jingoistic ideas is without question, and a form of resistance to that sort of thinking. But there is this fascination with juxtaposing the spiritual world, a mythic world, very much onto the physical architecture of the ‘real world’. A spiritual geography, and therefore some of the concerns in Amerika, and certain satires concerning that ‘bewilderment of cartography’, I felt was more than a little interesting when exploring Blake with Bulgakov. 6) It is fascinating the usage, in your two novels, of concepts or even names that, taken from their original context, gain new, unusual possibilities. These new possibilities endow such concepts with a flavorful mystery tone; this is the case of the fifth dimension in Amerika and the idea of Wollstonecraft in Europa. How, during your creative process, does the construction / displacement of meaning happens? I can sometimes get a little obsessed with semiotics, the way in which signs and words operate in relation to each other. I think essays by Roland Barthes, and some of the work of Umberto Eco are operating underneath the surface, in ways, in retrospect that I am still trying to understand myself. I think the idea in Eco’s The Name of the Rose, a book obsessed with texts, both real and imagined, (As in the notion that Aristotle had a Poetics of comedy, and not solely an investigation into classic Greek Tragedy) the idea of the censored forbidden text, etc, all I suppose have fed into this. I am, and am not, always completely aware exactly how this operates. I do not particularly reverse engineer concepts to put them into fiction. While I have an idea where certain things are going, I not plot these stories. I start them and they take me where they lead, and as I make that journey things begin to settle into a kind of structure. I think there is this kind of satire concerning that existential psychogeography in giving characters names of countries and concepts and similarly identifying them as individuals that both identify, and disassociate themselves with their moniker, often with varying results. Entirely displacing meaning from concepts and then re-contextualizing them, particularly to give them a kind of supernatural or occult context is something that is interesting to me in selective instances, I guess. I think it comes from the power of collage, of placing certain concepts and ideas in relation to each other to create new modes of meaning, that perhaps would not otherwise have arisen from them individually. 7) The dystopia in Europa is one of the most accomplished of recent times – humorous in its nonsense, preserving in this sense the satirical sources that are in the foundations of both utopias and dystopias. On the other hand, such dystopia is strongly connected to historical and recent events in an elaborated mixture – such as the image of Sherlock Holmes wearing uniform and armband. In this sense, what are the references and the method used to construct this particular kind of world? Thank you very much for saying that. William Gibson and John Scalzi for example, are always reminding us that science fiction that projects into the future, is really addressing issues in the present. Both incidentally are prolific on Twitter, and how I wish that we could have these two gentlemen, just for a week say, take over the current POTUS Twitter feed- that could just change the world and skew it towards a slightly (substantially) more pleasant and informed direction. In any case, I like the idea of re-contextualizing ideas and notions, and to resurrect and test them in a new context. It is also interesting to note, that in both Blake and Bulgakov, in different ways, are very much addressing the notion of time itself. Blake operates in this vast mythic time, and Bulgakov in a sense skews geographies and time as well. We have scenes of Pontius Pilate and Yeshua in The Master and Margarita happening concurrently with the events in Bulgakov’s present day Moscow. Those are incredible juxtapositions, and they provide all kinds of dynamic and powerful readings. The juxtaposition itself on the surface appears to also be a political act, but it runs deeper into a rather more mystical well, and if we read those sections rather more carefully, there is this cross pollination of subtle images that bleed into each other. It is remarkable and I think this notion of creating overtly political satire is not always that interesting, but on other occasions it certainly feels like it is necessary, particularly in these troubled times.

0 Comments

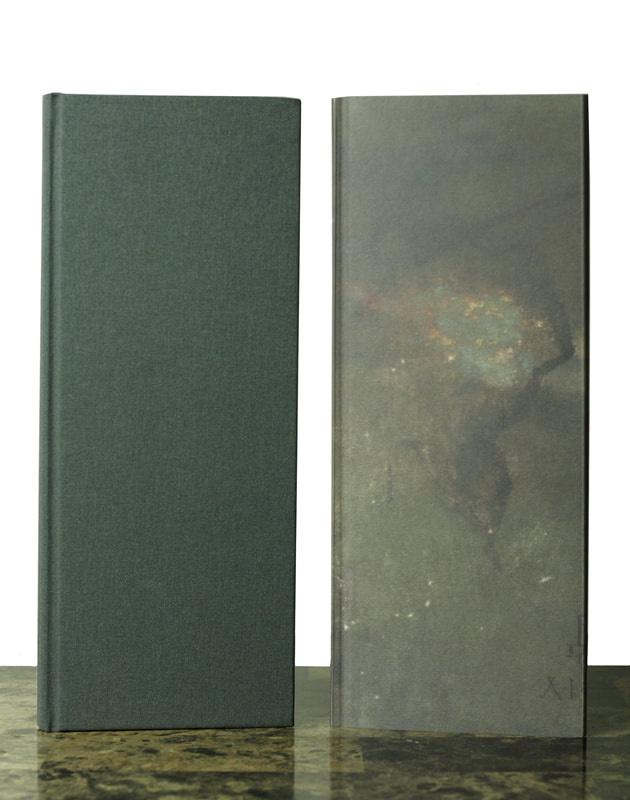

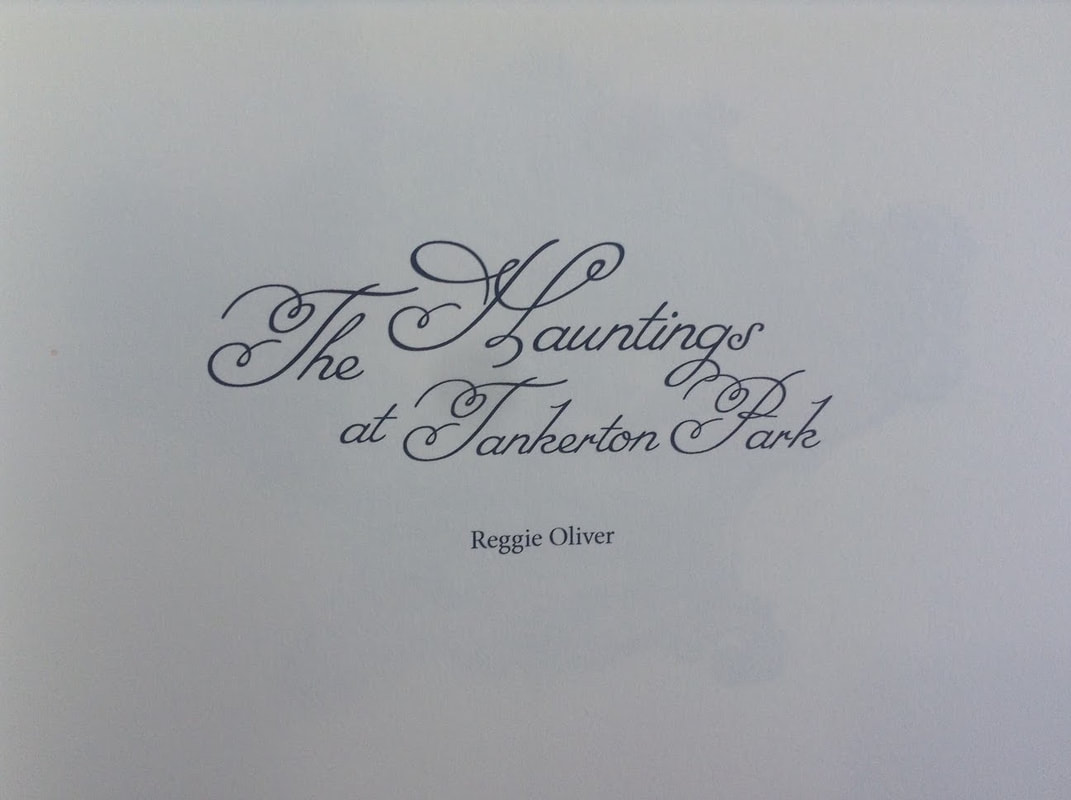

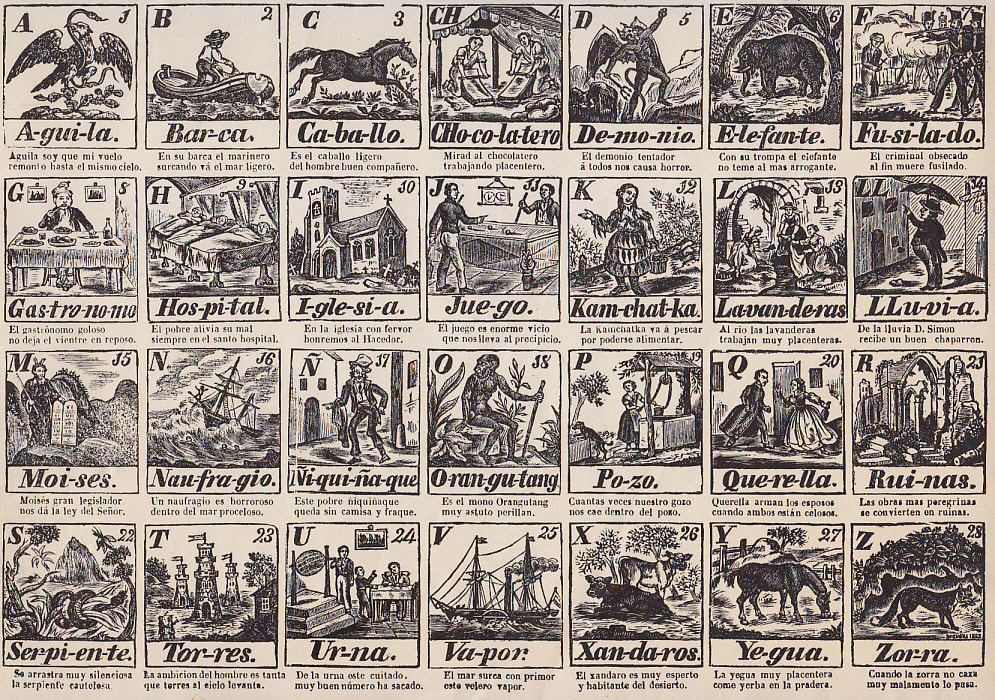

Perhaps one of the most perennial characteristics of Humanity is its tendency to avoid the incongruous, the unknowable. We opted for a easy and crystalline recognition of the objects that surround us – if we are to avoid disturbing experience of the freudian Unheimlich –, with no surprises or shocks. The multiplicity of human ingenuity and art follows the same pattern, and this, of course, includes publishers. The monstrous book is avoided, that is, the volume marked by heterogeneity and hybridity, and this behavior was established in Antiquity, since the privileged target is the harmonic whole, the expected result, the element easily recognizable and catalogable. In his Ars Poetica, Horace reproaches the monstrous book, consisting of unequal and disharmonious parts, stating that such senseless totalities are aegri somnia, these products of unbridled imagination, inaccessible to a conventional, healthy order. Perhaps Horace imagined that these aegri somnia were someday extinct, that the imagination would find a uniform path, that the human mind would conform to the aesthetic projection of the beauty that followed high standards of decorum. But he was wrong: despite all our organization, perhaps even instinctive, of all this pursuit of a purified imaginary, the aegri somnia persist, finding places unusual for its outbreak. Perhaps a worthy heir to this kind of construct that displeased the dignified Horace is, precisely, The Haunting at Tankerton Park, an illustrated book by Reggie Oliver, published with elegant and discreet splendor by the Zagava Press. At first sight, nothing would be unusual in Hauntings: it is an illustrated alphabet, in which each letter is illustrated by a verse and an image simultaneously. Below we have an example of this didactic literary creation (in Spanish) usually intended for kids, taken from the blog El desván del abuelito: In the case of Reggie Oliver's work, the illustrated letters compose a brief narrative, constituted by the act of assembling / disassembling the images and the verses. This is undoubtedly an innovation, although it has even been preceded by some other experiences, such as The Dangerous Alphabet, Neil Gaiman’s creation illustrated by Gris Grimly. However the Hauntings simplicity, austerity, and even conventionality is only apparent: it is a legitimate nightmare, an intricate manifestation in which images, verses and a narrative context become heteroclitical elements of a wholeness that resonates in the mind of the reader and which distances itself from the reassuring references of form or content. In this sense, it is the images that leap into the eyes of the reader immediately; extremely suggestive, they create a veritable grammar of Victorian interiors and atmosphere, including even the orientalist ornaments present in such style, as we see in the letter X of Xerxes. Oliver's drawing style, which he uses in the illustration of his tales, finds here a more subtle and direct expression, in which both the roughness of the woodcut and the softness of the chiaroscuro are emphasized, the transitions between light and shadows, which makes this work close to Goya's etchings. If the book were only these detailed images, these dizzying and suffocating environments in which the impossible, the absurd, occurs, Hauntings would already be a memorable book. But it goes beyond this thanks to two other intricated elements: the verses and the narrative. In the case of the verses, the author sought a certain singleness of the children’s poetry: “F was the Frog they acquired from a farm To eat up the finger that caused such alarm” The simple rhyme evokes the non-sense of childlike rhymes, yet retains the literalness of the element described in the grievous image of the giant toad devouring an equally disproportionate and inhuman finger. This tension between the form (the simple verses), the literalness of meaning and the image that illustrates the verse and that surpasses this seemingly limited functionality creates a remarkable effect. On the other hand, these verses escape the didactic functionality of the syllabary or the illustrated alphabet – Reggie Oliver is not meant to illustrate his reader by memorizing the letters of the alphabet. What he wants is to tell the story of a family moving into a Victorian mansion, finding in this new home the most unusual apparitions. This narrative eagerness disturbs the reader's perception, rendering the experience of this journey through a story with images and verses rather unusual and unique. In fact, the Zagava edition contributes to this, for being exquisite: I have, in my hands, the cheaper version, paperback. Even in its simplest incarnation it strikes from the cover – entirely in black, a negative of one of the many images in the book of Victorian mansions – by size, quality of print and format, makes the revisit of brief narrative a renewed pleasure. And, in fact, this repetition, the act of revisiting, becomes a fundamental pleasure in this brief volume. Walter Benjamin, the German philosopher who worked on such scholarly themes as the German Baroque drama, the narrator (from Nikolai Leskov), the concept of history and the Parisian Arcades, was equally fascinated by the inevitable materiality of the book for children, full of curious and strange idiosyncrasies. For Benjamin the children would materialize a verse from Goethe: “Es ließe sich alles trefflich schlichten, könnte man die Sachen zweimal verrichten.” (Everything would be perfect if one could do things twice). Repetition provides astonishing pleasure for the child; and Hauntings shifts its reader (adult or child) to this dimension of immense pleasure in repetition, to see again those amazing images, to repeat the verses, to remake the course of the narrative. Once again. And again. Note: Goethe's quotation was kindly corrected by Jonas Plöger.

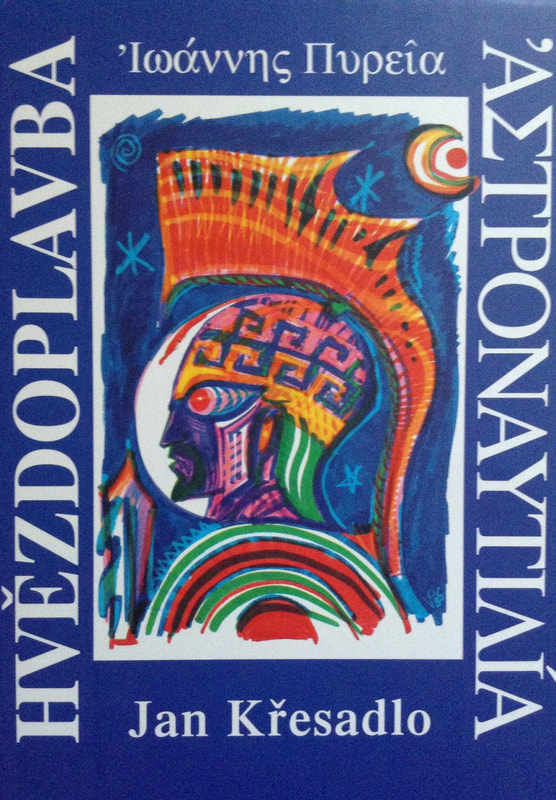

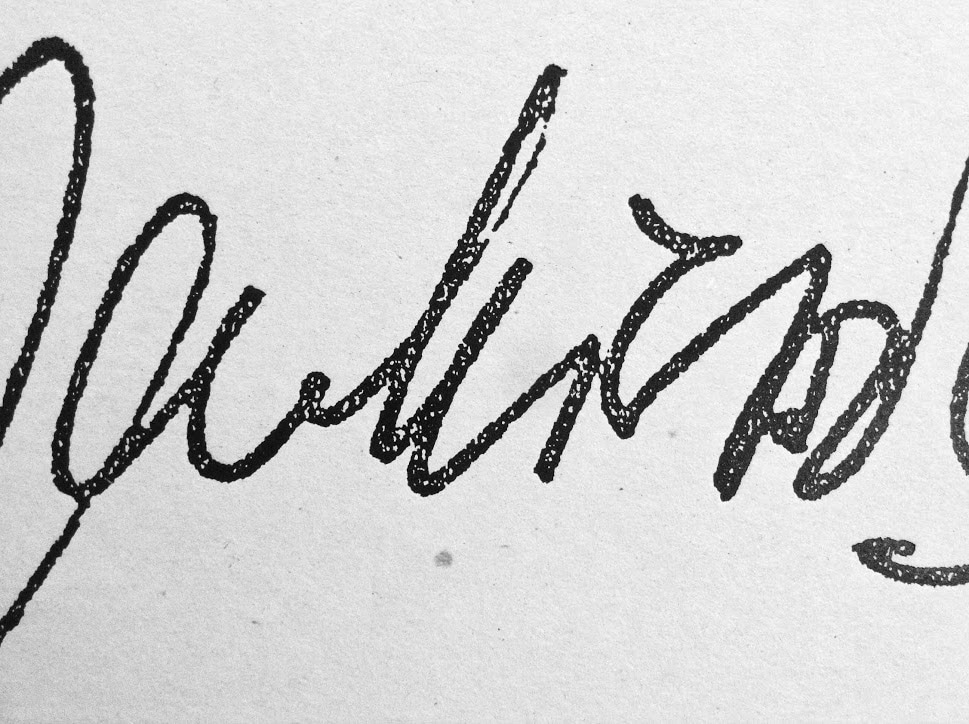

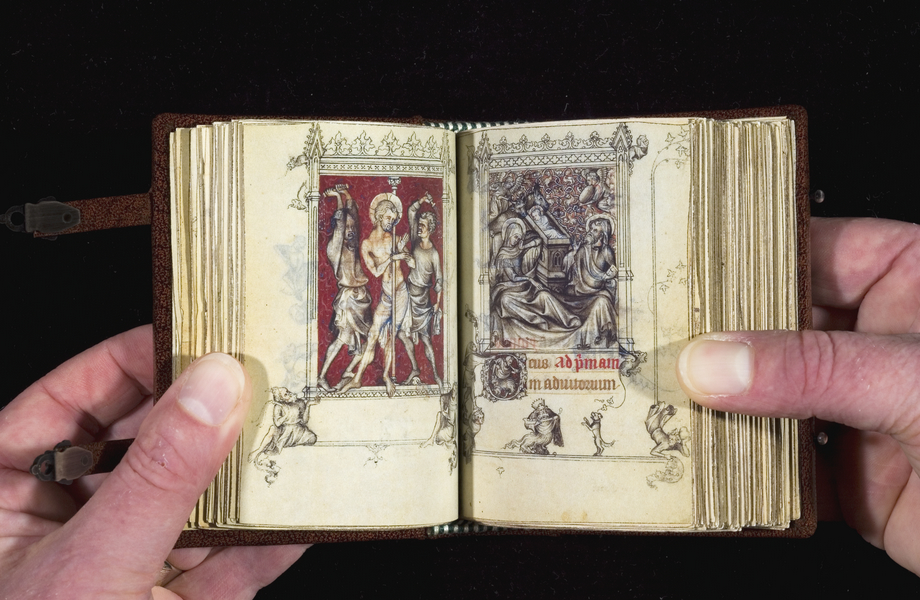

The old adage of Ecclesiastes (1:9), “nihil novi sub sole” – “there is nothing new under the sun” – seems to materialize in general a kind of rule, a ruthless, established and inflexible as steel rule. But the fact is that innovation, the novum need not arise from a brutal change, a revolution in absolute, total terms. There are amazing possibilities that arise from small nuances, handled with dexterity, skill, sensitivity. When faced with this kind of innovation, in a novel, poem or film, it’s possible to feel this kind of shine aroused by the masterpieces – something that someone can feel as soon as contemplate this cinematic "FIN", which closes John Howard's newest book, Visit of a Ghost. The novum of this brief (just over 35 pages) narrative by John Howard first comes from two aspects directly related to the plot. The first of them, already a well-known feature of those who accompany this extraordinary author, is the location: the imaginary city of Steaua de Munte. It is a triumph of Howard's imagination, obtained through the economic arrangement of seemingly trivial elements. The imaginary map of fiction is immense, diversified, from the legends of Prester John to Jonathan Swift, from William Faulkner to Gabriel Garcia Marquez. But Steaua de Munte is a strangely familiar landscape built patiently, its minimal elements (postcards, stamps, shops, coins) in conjunction with much larger ones (a world in which airships dominate all the aircraft industry), giving to the totality a fantastic figuration, almost of alternative reality. In this sense, John Howard seems to have in mind an excerpt from the poem "Juan López and John Ward", by Jorge Luis Borges (in the translation by James Halford): “The planet had been partitioned into different countries, each armed with loyalties, cherished memories, and an unquestionably heroic past; with laws, grievances, and their own peculiar mythologies; with bronze busts of great men, anniversaries, demagogues, and symbols. This division, the labor of cartographers, was good for starting wars.” The second aspect, in this sense, appears immediately in the title: a quaint idea of ghost. It is a fantastic element so employed in so many differentiated forms of narrative that its existence becomes almost derisory – the reader, in front of this word, initiates the mental process of accommodation of this concept in some of the innumerable possibilities already known and shared in the immense emporium of meanings available, recognized, cataloged. Here the two ghosts unfolds themselves, embracing aspects of it’s most simple aspects, however far from some innocent plainness. The encounter of these ghosts, two of them, is retained in much of the plot as a potential event, something that brings about an extraordinary quid pro quo whose complexity arises from an escalation of multiple incomprehension, something constructed in a simple but natural way, as many other everyday misconceptions. When these two ghosts finally converge, in a particularly extraordinary occurrence, such a climactic encounter reveals what may be the critical point of the narrative, in thematic terms: the discovery of another Europe, perhaps unfeasible nowadays, more open to the glance and presence of the Otherness. In that sense, John Howard's story brought to mind an essay by Ezra Pound titled "The Passport Nuissance," published in The Nation on November 30, 1927. In this brief essay, Pound vituperates against the formation of a new bureaucracy which, after World War I, made the disinterested activity of traveling more and more complicated. In that same spirit, one of the characters states (and this is the couplet that appears on the back of the dustcover): *My new book will be called Around Europe*. It is another Europe, potentially welcoming although surrounded by the usual tempestuous clouds of war, intolerance. But, perhaps, this is only a feasible meaning, a reading of many available. Physically, the book is extraordinary, magnificent achievement of the publisher Ex Occidente / Mount Abraxas. The balanced typography, the choice of photography as a significant element, even the use of this unexpected cinematographic resource, the "FIN" at the end of the book – it is a set of elements that follows the narrative in a subtle but indelible way. In fact, the use of photographic medium, allied with intelligent layout formatting, established unique, cinematographic effects. For, in fact, it is a story that could be on the screen of the cinema, specially a screen in the past, perhaps a puzzling film on the hazards of the nations like The Barefoot Contessa, The Last Command, or Mr. Arkadin. Some books have a special impact from their very existence, their being in the world; by not having a standardized presentation, a conventional exterior structure, become objects of fascination even before they are opened. Some present a strange, shocking or extraordinary cover illustration, this image being its source of magnetism more evident and concrete. Thus, the French translation by François Rivière of the J. G. Ballard’s novel The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), entitled La Foire aux Atrocités, published in 1976 by Editions Champ Libre – for the collection Chute Libre (“free fall”) – presents one of these extraordinarily picture with some striking layers. It is a kind of portrait, in the form of an illustration whose authorship is unknown, in which we have a face (female, probably) obliterated by blindfold and gag. The colors of the image (deep red, green, light brown, black that creates violent contrasts) are powerfully evocative, though the image itself has little to do with the content of the book, rounding the sex, yes, but not that way. Another more complex way for a book to express its potency in itself is by its volume, the way its outward structure is presented to the reader – in this sense, the recent collections Booklore and The Whore is This Temple are magnificent in a peculiar way. The first one, evoking the multiplicity of a library by its conflict between format and content; the second, because it is a kind of impossible object, a contemporary grimoire for personal rituals although it is not that, in fact, but a collection of narratives and poetic creations. Astronautilia is close to these two trends, but in a very unique way, because their impact happens in successive waves, that plays with expectations of the reader from one seemingly surpassed fright to another, culminating in a very own final decisive impact. In its dust cover, with a strong blue tone, a suggestive illustration by Václav Pazourek, the first image of the book and its real gateway: a portrait, in profile, quite colorful (the style suggests a vaguely primitivist expressionism) of what appears to be a warrior of the past, probably a hoplite of Ancient Greece. It is possible to identify in the image the shield, the helmet, the spear that this soldier holds. But the illustration, however, escapes this determination of meaning by a trait of technological futurism that runs through it – the white space between the face and the background of the image suggest an astronaut's helmet, adapted for use in sidereal space; the elaborate arabesques in the helmet suggest a civilization and a history that are not entirely human; the eye of the hoplite, at last, with a stylizedly almondlike shape and multiplied (by lenses? Or it’s an alien eye, in fact?) by the subtle effects used by the illustrator, a secure support for the odd strangeness. This extraordinary image covers and contrasts with the hard cover, much more austere – gently marbled dark blue, with the Greek part of the title engraved in silvery tones while the Czech part is in low relief – which refers to collections such as translations of classical and bilingual (Greek and Latin, of course) works published by publishers such as Éditions Les Belles Lettres. But the impact of the dust cover rich imagery, the fastness of the cover, and even the volume of this reasonably thick book constitute the first moment, preparing for the still greater impact with what we might call the linguistic discovery of its contents. For in the very first pages the reader is threw in a confusio linguarum of considerable proportions: there are texts in English, Latin, Czech – but all this is only the preparation to the poem, thousands of hexameters in glorious Homeric Greek handwritten. There are certain books that do not seem to exist-or rather, they seem to exist only as a fictional creation, a kind of imaginary interaction. Since Rabelais, whose giant Pantagruel spent his time in reading imaginary masterpieces that included a safe guide to public flatulence, written by a certain Magister Noster Ortuinus, not a few authors have populated their fiction, their personal universe with some shared elements with the continuum seem as common reality, with fictional, impossible books. These are volumes that, if they existed (something unlikely, an unfeasible technical achievement), would be like the lost volume of the Encyclopedia Britannica found by Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares in the tale "Tlön, Uqbar, orales Tertius" – part of a conspiracy against the foundations of our reality. But at certain moments we come across these imaginary books; our touch recognizes its textures, the softness of its pages and the graceful smoothness of its cover. Yes, this book exists, it’s not only a hallucination or a tricky that deceived our senses. But, still, we are not absolutely sure about that. The moment we find imaginary books (or that could be imaginary) is as if we find a breach in the continuity of a daily, systematic, prosaic, immanent reality. I can say that sometimes in my life I found these semi-imaginary volumes in the most common and uncommon places – libraries, small and large bookstores, second-hand bookstores, virtual bookshops, small publishers' websites (part of these books, incidentally, were reviewed here, in this blog, which came to life because of them). One of the last encounters with these books that seem to make the fabric of reality thinner and easier to crack - to break and become a mutated piece of imagery - was with the astonishing Astronautilia / Hvězdoplavba, by the Czech polygrapher Jan Křesadlo (In fact, the pseudonym of Václav Pinkava), published by Ivo Železný, an editor famous for his work of popularizing Esperanto. It is an amazing book that came from this distant land (at least from my point of view, a pedestrian in the southern hemisphere), which dissolves into an equally imaginary haze, from a small town whose curious sonority of the name, to a Portuguese speaker, sounds at once poetic and fairylike, the land of the Golem and Kafka, the Czech Republic. As I opened the package, I found a huge tome in a solid cardboard box. This case, at once rustic and functional, skillfully done, showed in its cover only the author's signature, in a convulsive calligraphy – a sure anticipation of the contents of the case, already visible in the spine of the book that such arrangement had exposed. For indeed, this content would be even more surprising. An exquisite book in more ways than one, Astronautilia / Hvězdoplavba will be the target, the first one, of a series of small bibliophagic videos and commentaries, which will open a new methodology of our blog. I hope it will please everyone (in any case, please send comments on this and other issues, if necessary).

"One after another all these earths are submerged in renovatory flames, to be re-born there and to fall into them again, the monotonous flowing of an hourglass that eternally turns and empties itself. It is something new that is always old; something old that is always new."

(Eternity Through the Stars, by Louis-Auguste Blanqui) After a long time of development, the crowdfunding project of the adaptation of the tale "The Extinction Hymnbook" – present in the startling collections The Gift of the Kos'mos Cometh! A Homage to Night and Kosmos and Lanterns of the Old Night – for a graphic novel, illustrated by young and talented Fabio Laoviahn, is ready and consummate. Some drawings can be seen in the gallery and the link to the campaign is available at the link below. Extinction: a Graphic Novel Project "Every poem, in time, becomes an elegy. (…) There are no other paradises besides the lost ones."

Jorge Luis Borges, “Posesión del Ayer” (The Possession of Yesterday) There are certain moments in our existence in which we plunge into some kind of abysmal contemplation, into the pure despair in the search for complex, definitive senses. These are the moments when, awake, we seem to have just emerged from a nightmare, those richly ornamented with sinister details of which we retain only a small part, which allows our awakening to be bitter, a rather poor relief. In these moments we think of certain abstractions, perhaps of our mortality (or the mortality of all beings, or of those we eventually love), but our thoughts are focused, with special acuteness, on the fortuitous character of existence and a certain notion of justice, and logic. Chaotic causality appears, in our eyes, as diabolical; because we seek an understanding that escapes from our hands, ruthlessly, so that a new world rises on our horizon, a world more sad and rough. We would like the world to obey the most beneficial arrangement possible, but this happy thought is just that: a ghost generated by anxiety in controlling the devastation of our grief. I can say that this dizzying sensation, so tricky to define and that seems to lead our consciousness to continuous dead ends, was that I felt at the knowledge of the death of Avalon Brantley, brilliant young talent who was not limited to the universe Literary that the French call littérature fantastique, but which expanded in a complex way by multiple and diversified landscapes. But, perhaps, this feeling that I have tried to describe above, in this case, can be classified as just an indiscretion on my part. For indeed, I was not a close or dear friend to Avalon Brantley. I have not even met her in person: our communication can be summed up by the exchange of electronic messages – some of them related to her participation in the Booklore collection – and an excellent interview that she gave me and which is published on my blog. It is necessary to emphasize that this meagre direct communication gave me the impression that Avalon was a person of good will, sensitive and of kind-hearted. In any case, I know little of her physical appearance, personal tastes, political choices or daily dramas. I was not part of her inner circle of friends and family, nor was I aware of the pain of the members of that circle, especially when they discovered her death. However, in fact, there was a possible connection, the only one in such cases, that established itself from a remote or recent past, between the creator of a story and the one who appreciates that work. For the extraordinary writings of Avalon enable an incredible experience to the reader – therefore a peculiar and intense communion. I remember the vivid impression of reading what I consider – from my point of view as a reader – to be Avalon's first masterpiece, coincidently her first published work, the Aornos tragedy, published in 2013. I hold dearest memories of the little books in this series, of the few that I have acquired, so precious and beautiful, and which were fundamental in many later decisions of my life. But I must return to Aornos: it is a tragedy, a play but, in fact, it goes directly to the reader who flips through its ardent pages, proposing an extremely exquisite and daring experience, a visionary form of Theater for the mind, so complex in evoking its elements and in the effect of its irony. The flow of the mythological and religious elements of antiquity is intoxicating; It seems that we are facing some lost and particularly perverse creation by some author of ancient Greece. It is very difficult to escape the sense of destructive inevitability of fate when, at the end of the play, we find ourselves like that chorus of cicadas conjuring the presence of a fearsome female in a catastrophe nourished by true love. That was only the first book by Avalon, her spectacular presentation to the world; other creations would emerge, both materialized in books and contributions to collections. Unfortunately, I do not own all these works – I am not a consummate collector, specializing in completing a given collection of literary butterflies, such as those editors chosen to preface the complete editions of certain authors in the series “Bibliothèque de la Pléiade”. But some of them, which deserve mention, I had the pleasure and honor to read. All these works point out a secure fluidity between different genres, formats and conceptions – some of extreme radicalism – but also an acute perception of the ironic, cruel traps of fate that the author had already so well represented in Aornos from the tragic perception of existence nurtured in antiquity. Thus, shortly after Aornos, we have a collection of short stories, Descended Suns Resuscitate. The golden cover has a marbled texture that is extraordinarily tactile, while a small circular hole points to the symbolic and photographic clue to certain elements of the book, notably a certain atmosphere of inevitable, painful nostalgia. The tales, set in floating historical landscapes, are dominated at the same time by the overwhelming perception of fate and a really exquisite sense of humor. In this sense, it is worth mentioning a narrative like "The Last Sheaf”, which presents a balance between these two poles that were obsessively revisited by the author. The final tale, called "Kali-Yuga", presents this visionary characterization that already transpired in Aornos and that would grow in terms of conceptual sophistication in her later writings. Apparently dissatisfied with the tragic closure offered by fate in its cunning configurations, she would seek in the image of creation/destruction, increasingly freed from its limitations, new syntheses. Thus, the next release would be Transcensience, the penultimate full book of Avalon, written in collaboration with Locket Hollis. The book jacket in neutral, icy, creamy color, revealing Egon Schiele's fine incisive features and the initials of the author and co-author on the spine, just AB/LH. In the frontispiece, very appropriately, a frame of the film Le Sang d'un poete, by Jean Cocteau. In the book, brief narratives, poems and poetry in prose alternating, making the book unstable, a challenge to this perennial search by every reader for something near to the sense of fullness and harmony, the security of stability in literary terms. But instability isn’t the same as inconsistency, the fragility hidden by the mask of certain formal dances; on the contrary, the book presents a thematic identity around the idea of death, of the passage, of the threshold, of the ineluctable. In this sense, there is a constant fluctuation in the approach of these concepts, between poetic subjectivity and narrative objectivity, between the pathos of poetry and the necessity of verisimilitude eventually imposed by the narrative. The heart of the book is precisely the brief narrative "The Far Rest", a title that carries a anagrammatic game with the threatening "forest" that haunts the whole tale. By breaking the boundaries between poetic subjectivity and narrative objectivity, Avalon reaches the paroxysm of despair in this brief narrative, culminating in an utterly visceral longing – which is expressed by a fragmented language – by a lovely, immense potential god. It is a deepening and subversion of what we have seen so far in Avalon, from Aornos; for it, at the same time, has subverted the general boundaries between narrative and poetics in the same way that it recovers some of the deepest yearnings and anxieties of the literature of the past. What she had done with the Greek tragedy, she accomplished, in Transcensience, with the romantic poetry of the nineteenth century. But the truth is that the deepening imagery and the increasingly direct narrative formulation of despair showed, indirectly perhaps, her suffering, a suffering that threatened to isolate her subjectivity definitively, with the ultimate abandonment of writing. However that was not what happened. I mentioned Avalon's various contributions to collections published by small publishers in 2016 and early 2017, a “particularly productive year” in Avalon's own words. They are small jewels not only in the sense of the astounding quality of this material but also by the altruistic nobility expressed in her will to expose the demons themselves, to exorcise them, to sublimate them into literary works, for the scrutiny of the public, that she sensed perhaps sensitive. Among these material, I would like to highlight three extraordinary creations whose analytical reading could indeed feed into academic research if it were not so far removed from the more vanguardist reality of literature by the compact walls of self-complacency. The first of them is "Nocternity", which presents the most visionary side of Avalon already in its title, a strange fusion between "Nocturnal" and "Eternity". The tendencies of Transcensience become even more radical: the alternation between verse and prose builds less a dance between poetry and prose and much more a kind of liturgical hymn, the multilayered evocation of new and old gods. That is, a unique construction because of its intricacy, which plunges the reader into myth directly, abandoning the usual conventions of literary genre. But this diving would be the prelude to an even more ambitious work: "Corpus". According to the author herself, the inspiration for "Corpus" (the very significant subtitle is "A Mandala of Anatomy and Metaphysiology") came from certain works by Andrei Biely, such as Kotik Letaev and Glossolalia. It is the author's version of the biblical Genesis, a union between the broad perspective of the universe and the intimate development of consciousness in a unique form of synchrony, in which language fragments into pieces corresponding to sensations, to the potential link between the boundless and most profoundly personal. The editors perceived the importance of this piece, so original: in fact, “Corpus” not only follows a unique format within the collection (in two columns), but is the only one immediately illustrated. In a way, it is the apex of visionary work and the subversion of literary forms and genres by Avalon. It would be expected that the author would later adopt more and more radical forms of disruption with narrative and poetic structures and even with language. But behold, the multifaceted personality of Avalon arises and presses into another, somewhat surprising, way. It is a path subtly indicated by herself at the end of her extraordinary mandala, when she states "god left the house”. This path begins to be indicated in the third piece I selected, "A Dead Man's House”. After experiments in the borders of language and the subversion of the usual literary structures, Avalon returns to the fantastic tale, a genre that she has approached so skillfully in her Descended Suns Resuscitate. "A Dead Man's House” is a tale about the potential existence of books considered lost, with astounding developments and speculation. The reader's imagination is spurred on by the imaginary reconstruction of such vanished volumes which, in the end, receive a fateful and liberating destiny, a spectacular auto-de-fé in the same vein of previous rituals performed by Elias Canetti in Die Blendung and Jakob Wasserman in Das Gänsemännchen. This renewed return to narrative sources, on the other hand, marks the last book of Avalon, the novel The House of Silence. It is, at first glance, a tribute to William Hope Hodgson, especially to his The House of the Borderland. But the last story (which, curiously, would be her first novel) of Avalon is much more than that; a visionary narrative, although quite simple, that takes up with great freedom the tropes of the weird and horror genre. The visionary radicalism of the author's earlier works, which seek a break in the relationship between language and objective/subjective reality, still manifests itself here (there was also something of this breakdown in the narrator's role in "A Dead Man's House") but in a subtle and controlled way. It is in the dream universe and in the sensory perceptions (even the simplest) of the protagonist and of the other characters that one realizes the potentiality of this break in the fabric of the real. Revealing to the reader the horror of the limits of perception and rationality in a cadenced rhythm, by its perceptible edges, Avalon revealed an extraordinary awareness in the construction of this long and fascinating narrative – her last one, unfortunately. In her work, Avalon Brantley demonstrated the limits of language and perception, the misleading separation between the individual microcosm and the collective macrocosm, the subtle and sadistic traps of fate, the abysmal and evocative vertigo of the Vision, this form of apprehension of universal knowledge adopted by Swedenborg or Blake or so many others before herself (and many others later, I hope). The rereading of her work becomes a painful and moving exercise in the light of her death, but we must interpret it further, for death – in more than one sense – is not the end. Pier Paolo Pasolini understood death as a final cut in the long take of life; a final cut that concatenated the previous acts in an edition full of meaning. We could go further (inspired even by Pasolini's own terrible death): the definitive cut in the film of life with the death is in some cases an enigmatic product whose apparently clear sense holds as many possibilities as secrets. Following this line of thought, though the shock of loss may exist, Avalon left a long and enigmatic narrative represented by her works and the mysteries of her sadly short existence. And even though I regret not knowing her better, I know that I can revisit the brilliant, animated by a everlasting fresh existence in her works. Not by chance, one of Avalon's last testimonies makes it very clear that she, like Blanqui and Nietzsche (or Borges), believed in the infinite plurality of worlds, of existences, of lives. In one of these plural worlds she continues to build her work, sung by aoidos and other vagabonds or poets like the songs of a close brother, Homer. This piece would not be possible without the generous collaboration, reading and suggestions by Jonas Ploeger and Jonathan Wood. The Hours of Jeanne D’Evreux (photo by medievalfragments). A whole new mythology could be developed based on the possible books, those who have been imagined but never written. Or lost forever in one of these History’s plot changes, always cruel to the weakness of the imagination. In this sense, there is a tale by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges that appears to offer a terribly enticing prospect for any writer. This is "El milagro secreto” (The Scret Miracle) part of the “Artifícios” section in his Ficciones (1944), which tells the story of a poet who, after quick conviction by a Nazi court, is facing a firing squad. He worked in a particularly difficult tragedy and his desire would be finish it before the bullets of his executioners rip apart his body. It was obviously a vain hope, but some divinity heard the poet and awarded him an extra year between the time of shooting and the impact of bullets, so he concluded his work. This was done and as soon as the last fixes were completed, the bullets were put in motion again. The poet, protagonist of the story, did not have time or possibility to realize his definitive work on an appropriate editorial format; only his memory and the deity who heard him would know the content of what was projected in his mind. So the author and narrator, Borges, provides the reader with not a reproduction of this unusual work, inaccessible and not registered, but its uncommon route. In this sense, Mark Valentine offers to the reader the same in his Wraiths – the winding path, unique and complex that never got to take shape or become visible.

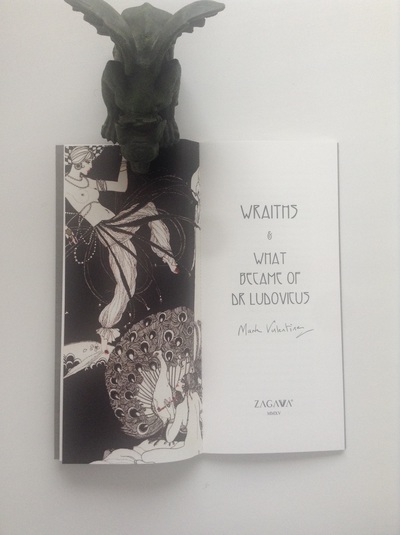

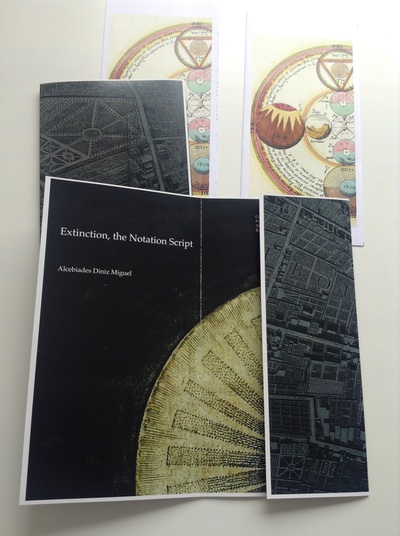

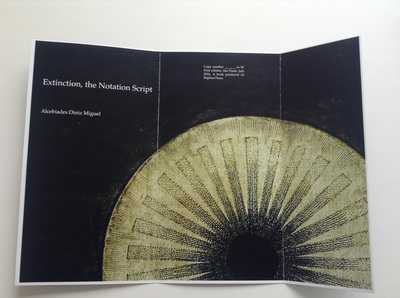

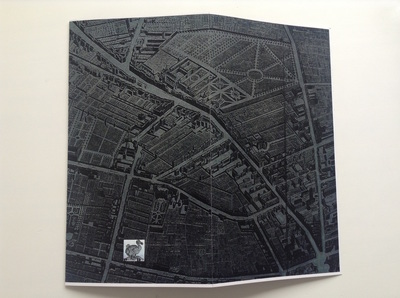

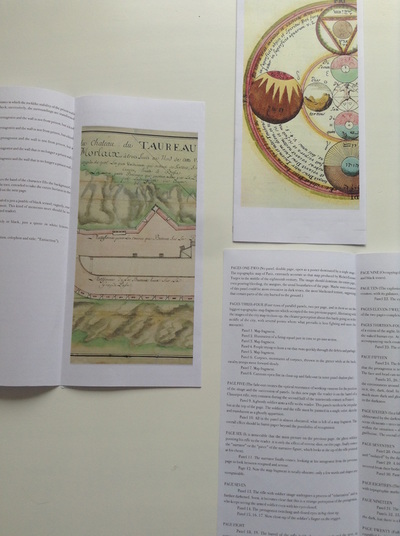

The essays of Mark Valentine is vibrant, innovative and suggestive. One aspect of these essays, no doubt, is the approach/recreation of lost, unfinished, invisible literary works. In Wraiths, there are two essays focusing on the specific form of non-existent creation and not materialized potential that entices the imagination of a very specific kind of animal – the bibliophile, a kind of people who nurtures this obsessed, sometimes excruciating, fascination on book as object, form, idea. The first essay, "Wraiths", deals with the poetry books that were probably produced at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century in England, but that apparently does not exist. This time was populated by books of short poems, precious little jewels of the publishing industry, but not all have this essential embodiment, the final book form. The books of imaginary poems described by Valentine are as complicated mirages, whose existence is attested even by witnesses, but that vanished and left no trace. Valentine, in this first essay, use these testimonies, these indirect evidence to handle such invisible corpus; it is an intelligent methodology, because the indirect evocations bring the reader something unusual about the lives of the kind of dematerialized masterpieces creators. This evocation provides, by a paradox of representation, something like a glimpse of the lost poems. Cause, in fact, such non-existent creations go even further than these sparse and vaporous sonnets that Mallarmé wrote for printing on fans. The authors of lost works reached something like the accomplishment of an imagination utopia: the poetic construction as short, soft, sophisticated structure, which is diluted in ominous or happy fragments in the very existence of the poet and his time. The second essay, "What Became of Dr. Ludovicus", deals with the creation not performed adventure in a even more intricate level: a lost novel, which was written by four hands between Ernst Dowson and Arthur Moore. It was a "shocker", which was the way the Victorians termed novels with bizarre, disturbing and/or supernatural central elements. The essay follows the production of the novel in the letters exchanged between the two authors; the level of detail of this production process, evoked by Valentine, is quite large, including details such as the use of a notebook with shared writings that both authors employed to write the chapters. The reader thus follows the development (sometimes problematic) of each chapter and the fate of the finished material, systematically rejected wherever the authors try to publish it. Would be a fair rejection, given the quality, editorial or myopia, as often before a interesting material? Valentine leaves this question open, stressing however – with his bibliophile soul – how interesting it would be if the book had been published, knowing its narrative and its creation process, both seemingly rich and tumultuous. This is perhaps the most obvious essence of the Wraiths, the connecting link between the two essays: the desire for the existence of a book, in a way, can make the reader itself (which already became a researcher investigating the tracks of his passion here and there), by a sort of evocative magic, perform this conjuring of a lost book that makes out of nowhere appears something. As a book, Wraiths is a delicate and precious object, indeed a beautiful tribute to the fin de siècle editorial art. Only the title appears in golden on the cover – a sinuous font seems to mark here at the same time daring and restraint, the only distinctive feature in a rough and gray paper, reminiscent of the stone, a texture little polished but rich in nuances. The two Ronald Balfour illustrations that open the essays seem to evoke in a starkly and not overloaded way the Victorian era. Interestingly, the Mark Valentine book today is partly invisible – the Zagava publisher reports that the print run of 50 copies is already out of print. Although the essays can be found in other books (notably, the excellent collection of essays published by Tartarus Press, Haunted by Books) the preciousness of this little booklet, so slim that could disappear at any moment, it is irreplaceable. The special edition of Extinction, the Notation Script is finally ready. This edition is in accordion format, with special elongated jacket and two very significant images (those who know the story and this script will understand the meaning of these images). The special edition version will have only ten copies (subsequent copies will be released in more conventional booklet format, with A5 size). These special books are still available at this link (there is also a digital version in epub or PDF format).

(The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, by Albrecht Dürer) The wheels for torture were broken with the explosion and death of the executioners, and the sky blasted and roared with a hailstorm, while the earthly fire departed from St. Catherine, she had the neck sliced by iron and thus ended. But there is something more in this picture, or better it most completely written in eternity by the carvings in the wood. The wheel is the center, a little eccentric, as is the center of a fan, which is full although not round. And there is a crank for moving the wheel and this wheel is double and the two halves rotate in opposite directions, as also opens the fan. The wheel is the center, a little eccentric, as is the center of a fan, which is full although not drive. And there is a crank for moving the wheel and this wheel is double and the two halves rotate in opposite directions, as in the open fan’s movement. The flames flow according to this rotation like water from a mill, and the soil’s fragments of the hill rush towards them, which continue them, and the trees above are further stacked in horizontal pieces that go down from the right section, as a cloud, and feed the turning of the wheel. The rain of heaven falls according to both sides of an isosceles triangle whereupon these horizontal sizes are based; the filled basis folds itself (shaped as a pluviometer) and creates the right arm of the executioner, raising cloak and sword at the right side; the left arm remais covered, as the wind rises his coat from the ventilation fins of the blower wheel, the two ears of a pentagon or reversed kite; and the shape of the triangle is visible too, to signify God: the fire of the Father between co-personnel clouds. And above the city, which is carried by the wheel, there is a hill that descends from the sky, and drops to the ground where are the dead executioners and recall the leaves around the wheel; and there are three stages in the image, to signify the three worlds. The hill flows harmoniously with the folds of the dress and the beautiful curved line of the gastrocnemius muscles, which are the Dürer's legs. This dress and these legs are the tail and the dress of a greater Saint beheaded that fills the image, with the croup on the shoulder of the executioner, the navel on the eye of Catherine, the cut in the horizontal terminal line to the pieces of the hill. The severed neck ends according to the hard edge of the a man fleeing radius, in the extension of one of the features with clouded nuance that is more thrusting than sword. And the head and the hair rolled from the city and trees sloping towards the mill wheel, for the new gyration. Alfred Jarry (Perhinderion, n. 02, June 1896) Above, as an introduction to the new Raphus Press book series, the translation of a brief review by Alfred Jarry to the expressive, troubled and apocalyptic Dürer's engraving about Saint Catherine last moments. The first book will be a translation of the Jarry's creation to his other imagery magazine, L'Ymagier, plus a introductory piece, a imaginary portrait/exegesis.

|

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed