|

Albert Speer, the German architect, a personal friend of Adolf Hitler, developed in the 1930s a “theory of ruin value”. Faced with the vision of the imposing monuments erected by the Nazi regime (like the famous Zeppelinfeld, designed by himself), Speer had a vision of that huge stadium complexion hundreds, thousands years in the future, when Reich himself had shattered and everything was decay and ruin. Speer wrote on his theory: “He [the architect] chooses the stone, which can offer him all possibilities to form, and which is the only material to pass down tradition—the tradition that remains for us in the stone buildings made by our predecessors—to future generations because of its constancy”.

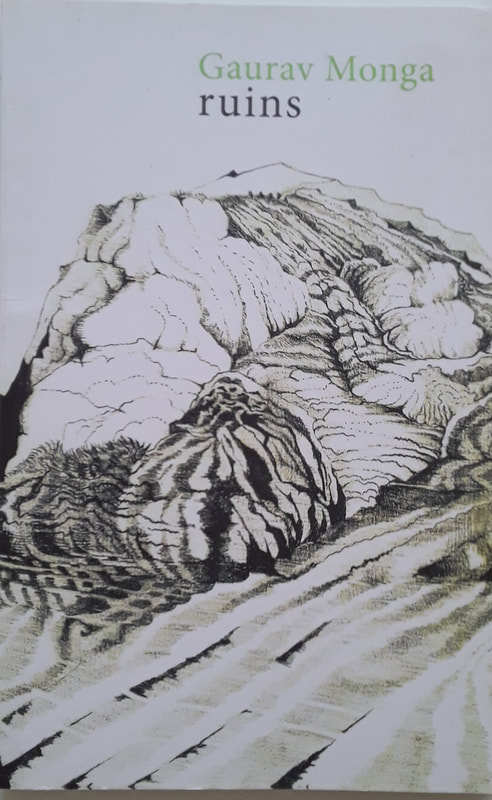

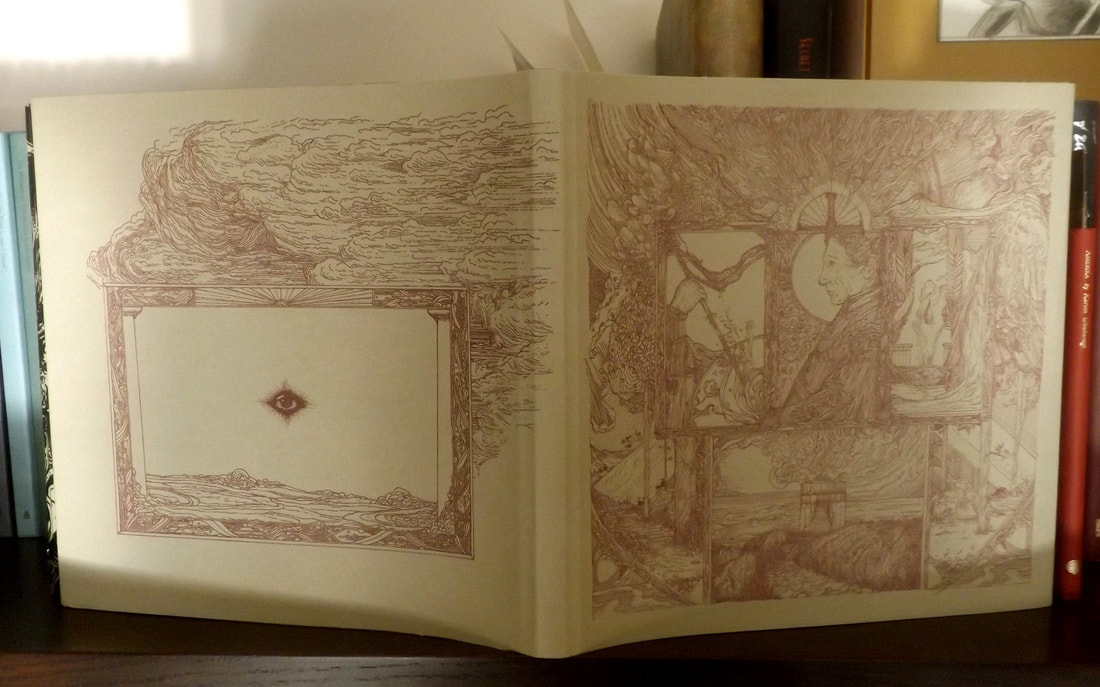

This was the fascist theory of ruins, which intended to find mythical value in the piles of rubble, a static and perpetual, in addition to boring, ritual. But Ruins, Gaurav Monga's new book (edited by Desirepaths Publishers with a beautiful cover art by Anil Thambai, in which the suggestions of the organic and inorganic, the built and the natural, are prospected), offers us another possibility to understand the ruins – unpredictable, complex, stimulating. The ruins imagined by Monga were scattered in every corner of our society and even the newest buildings, in the pages of his strange book, are already decaying relics. Monga's prose is blessed by vast subtlety: a mixture of narrative perception, vague memory, aphoristic speculation and poetic meditation, it escapes all possible definitions and points to insidious and indeed innovative directions and developments within the cultural perspective known as neodecadentism. New horizons, explored from trailblazer perspectives that go beyond even the most subversive grounds inherited from psychogeography. In several moments of Ruins, Monga speaks of the childlike pleasure of collecting fragments of the piles of rubble abundantly available in the big cities, constantly under construction/demolition to a point where it is no longer possible to identify where the ruin ends and the new building begins. This is the pleasure that the reader can obtain from this Gaurav Monga's book.

0 Comments

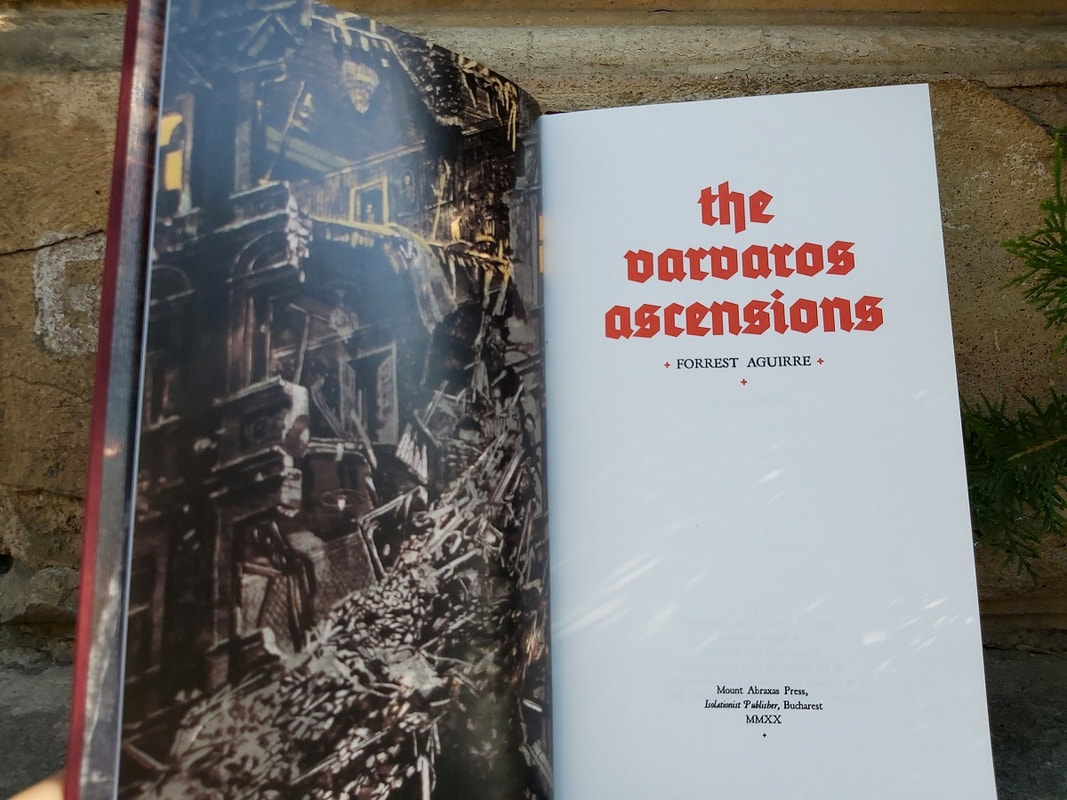

"The Eastern star calls with its hundred knives Burn the cities Burn the cities" (Nathanael West, "Burn the Cities") Photo by Dan Ghetu. It was in my days at college, when I was studying linguistics at the University of São Paulo – when I get this strange pleasure: going through the library corridors at that university, without any specific target. I was not exactly aware of what I was looking for - but I did it furiously. Even when consulting the exotic urban theories, reflections on the city, published by the Spanish publisher Gustavo Gili. At the same time, I was exploring the gigantic metropolis, São Paulo – again, I was looking for something that I myself didn't really know what it was. Perhaps it was something new, unique; the hermetic; the vertiginous; somethng that, even when invisible to all, is not perceived in all its magnitude. Maybe it was something I could never find directly, like an item on a shelf, a fixed point on a map. I believe that my search was centered on something magical – a key, a cipher, a code, any element that would undo the fabric of the world, that would destroy the space-time continuum definitely, a very destructive leap. Forrest Aguirre, in his superb work The Varvaros Ascension, offers, in fact, not one but two of these strange keys to undo / remake the world – the City and the Ancestry.

But before the description of these strange gifts offered to the reader by the author and the editor (after all, it is not plain thing to witness the development of two bloody, sacrificial puzzles, in a single interpolated narrative), a slightly more formal presentation of the narrative is needed. Perhaps even something academic – as that would not be unfair to the author, his plot and his text. In fact, the world of universities – theses, scholarships, master's degree, doctorate, post-doctorate, professors who are researchers as well, researching rituals, classes, baccalaureate – all the strange university mandarinate is part of the intricate narrative of The Varvaros Ascension. But such involvement is far from making the plot unpalatable or tedious as such university settings are often; Aguirre's story is agile, fast, good-natured and extremely inventive, something that we would see on television series if the showrunners of that television shows were people like Fritz Lang, Raoul Ruiz and Hiroshi Teshigahara. Or Nigel Kneale, who once, in some dimension of the temporal continuum, worked on television shows. Aguirre's novel is tricky because it follows in a kind of double helix, in a potential that goes beyond the initial presentation of a title (The Varvaros Ascension) in favor of two other subtitles ("The Arch: Conjecture of the Cities" and "The Ivory Tower"). From this first carrefour, we even have a exquisite name as the title of a diegetic book – but it could be a perfectly real book, in some obscure academic bibliography. Indeed, it is not even a book at all; and Aguirre's story following this strange mystification, tracks that formed several other books, which are opened to the reader's eyes thanks to the author's visionary capacity. There are inscriptions, signs and modes of reading in the city (Madison) that surround the characters, at the university, in the friezes that decorate one of the buildings, in the disposition of beggars, in the bones – ancestral and new. All of these books are thought provoking by the vision of the author, who manages to distill from the arid urban environments in the vicinity of the universities a dense and disturbing cultural broth. It is as if Arthur Machen had attended courses at university with Herbert Marcuse as a research advisor (at Columbia University). As usual, the edition of The Varvaros Ascension, published by Mount Abraxas, is superb. The cover, with illustration by Valin Matheis, alludes to primeval, rupestrian and ancient images but, at the same time, to the fallen angel (in inverted presentation) of the Limbourg brothers in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The inner pictures, portraits of urban desolation, perfectly follow the imagery of Aguirre's narratives. This new book is impeccable en every way (as usual in Mount Abraxas books) and the unusual format make this book an unusual cult object – the strange artifact to be used in a strange new ceremony. And now, it’s time to see the book's apocalyptic potential, duplicated by the narrative. The protagonists of the two parallel plots – which meet, literally, in the infinite – are the explorers of an other reality, materialized in a specific type of narrative that, the two protagonists soon discover, make our conventions usually accepted absurd. What narrative would that be? Well, the one that occurs in this exquisite book, The Varvaros Ascension. And faced with the tasty trap of this loop, we seek repetition: for we will read this book again, many times, and it will always seem intricate and hallucinated in a enticing way. The title’s ascension speaks of us, readers, transformed into pilgrims in infinite progression, searching for the new signs for others – many, endless – apocalypses. Photo by Alcebiades Diniz Miguel. Photo by Dan Ghetu. The subtleties of a mind in the process of disintegration; a very plain, usual mind, which we saw every day in our daily lives, but in the moving from its usual compass to new and unexpected directions – a recurring theme in literature, indeed. This intimate, dark journey is at the foundation of much of Edgar Allan Poe's fiction, for example, with a kind of character that deliberately destroy its means of existence, driven by a vague feeling of horror at normality that the author called perversity. In most of the fiction made after Poe, which traces these uncertain steps, some type of psychological penetration, of exploratory diving into the sick conscience is sought; even Dostoyevsky chose this direction. But there is another way – the dazzle in the face of disintegration. There are, therefore, works that choose to contemplate the complex processes of the mind on the verge of extinction to obtain a certain degree of ecstasy – the investigation becomes a poetic, sacred rumor. So, it was with Lautréamont, with the surrealists, with Alain Robbe-Grillet and it is, likewise, with this spectacular fiction creator, Jonathan Wood.

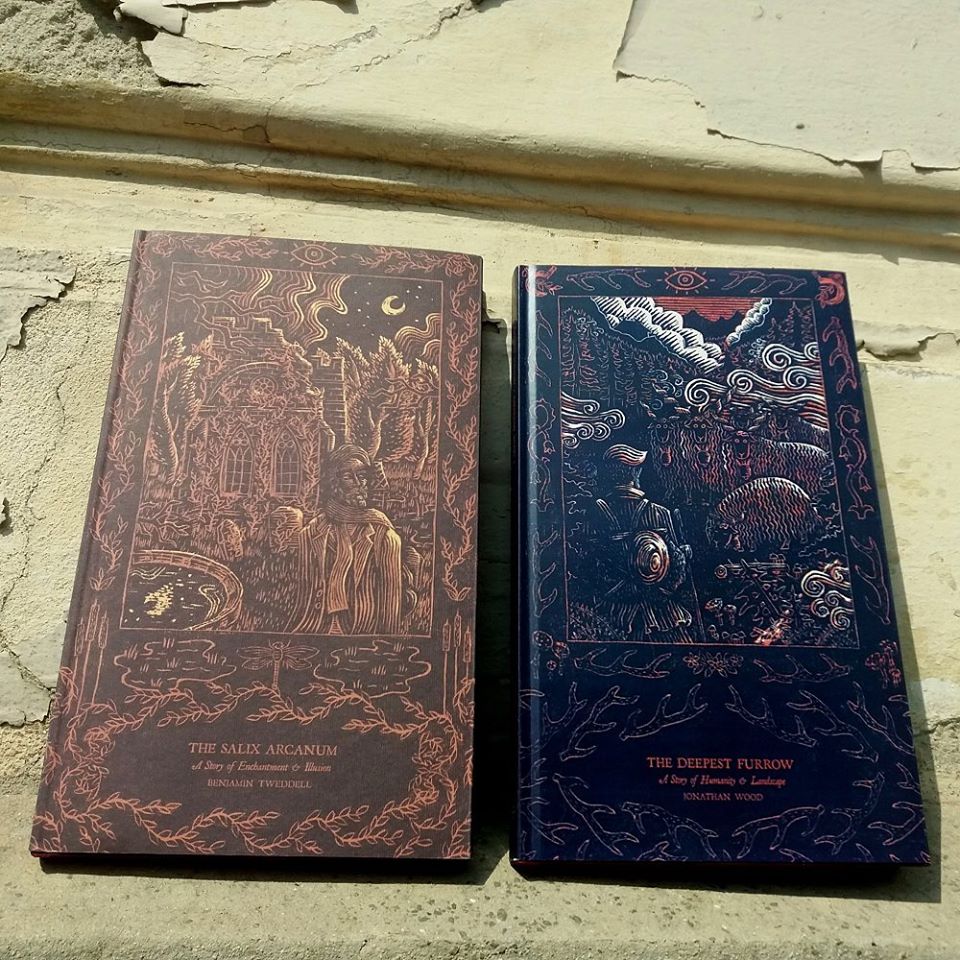

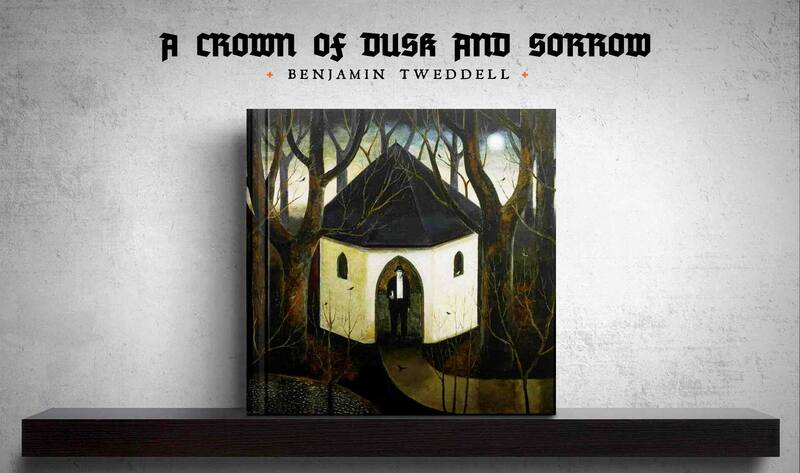

Evidently, Jonathan is far from a neophyte in fictional creation. He is a poet, short story writer, novelist and editor with vast production of exceptional quality. And he is a true craftsman of the short narrative. One of his best novelettes, The New Fate (2013) already worked on the themes of division and rupture of the mind in a dizzying, catastrophic and ecstatic context, which leaves the reader with tears in the eyes at the end of the book; tears of sadness and joy. In a way, these two new novelettes, The Deepest Furrow and The Delicate Shoreline Beckons Us, edited in the same year, 2019, revisit that former masterpiece, but with a different and quite rich articulation, a clearer option by narrative frames that can underline the dense elements stirring within the plot. I've seen criticisms about Jonathan books, reporting how his works are a bit abstract, which creates a certain difficulty in connecting with the characters. In the two narratives of 2019, this connection is certainly immediate, without the loss of the speculative abstraction. Both narratives seem to reach different thematic and stylistic points, from a philosophical perception – but there is a poetic insight more or less common to both. In other words: they work aspects of the human mind (terrible and dreadful, no doubt, but also cyclical, ritualistic) from a casuistic perspective translucent to the reader. In the case of The Deepest Furrow, the frame is of what is conventionally called "folk horror"; but Wood's philosophical approach is so dense that it goes beyond the mere conflict between city and country, Christian and pagan, civilized and barbaric (so usual in this kind of plot) for a nihilistic view that embraces all human perspectives in the same constant spiral of oppression and extinction. In The Delicate Shoreline Beckons Us, we have an almost police narrative from the perspective of criminals, a "caper" as specified in the introduction by Mark Valentine; but again the protagonist's cynicism in no way easy piece for any formulaic on the heroic redemption trope. The power of Jonathan's plot goes beyond the limits and boundaries established by the narrative frames he uses for his paintings of despair and death – but also of ecstasy and transfiguration. The two books are also expressions of different beauties – there is an unassuming and engaging abstraction in The Delicate Shoreline Beckons Us, edited by Zagava (my edition is the paperback, but there are much more luxurious options on the publisher's website), with the undefined photographic image on its cover, suggesting the flow of sea waters; there is a baroque fury in The Deepest Furrow, expressed notably on the spectacular cover of Matúš Ďurčík, incredibly intricate like Jonathan's own story. This opposition usually follows in both and creates a spectacular contrast. It may be necessary, however, to highlight the cinematographic aspect of Mount Abraxas editions, a rich trickery suggested by the very paper on which the book is printed and the its general structure. But this consideration is about another level of meaning. It is interesting to compare these two Jonathan's short narratives with recent films that have followed similar and specific paths, but without the same thoroughness (although, without a doubt, both are good films). Midsommar (2019) by Ari Aster can be compared to The Deepest Furrow and The House That Jack Built(2018) by Lars Von Trier, with The Delicate Shoreline Beckons Us. But the films are still framed by the clichés of their genres, by the devices used in their making; Jonathan's novelettes flow through the wild territory between vision and thought with much more freedom. The richness of Jonathan's stories may one day reach the cinema; but perhaps the best is to enjoy them in the infinite breadth of the printed pages of these two superb books. The Idolatry of King Solomon, Salomon Koninck, 1644. "Then with that faint light in its eyes A while I bid it linger near And nurse in wavering memories The bitter-sweet of days that were." (The House of Wolflings, William Morris) Perhaps one of the most recurrent figures in the narratives produced by the mankind is the king, the crowned figure; it appears frequently in legends, fairy tales, myths, sagas, chronicles, novels and poems of the most varied types, even in the most popular representations of contemporary literature and cinema. Sometimes, this regal figure manifests itself as a powerful overlord; in others, as a warrior; it can also be represented as a God or as a dim little figure in the background. There is dignity in its presence, sometimes hope (as in the notions of the order return, cherished in Arthurian myths and Portuguese Sebastianism utopias), but also melancholy, a vague resonance of the power and wealth that these beings have in the realms of reality. But sometimes there is madness, and horror, and tyranny, and death, as in Shakespearean tragedies, or in films about the loneliness of power – after all, the political leaders of totalitarian regimes mimic something of the cursed flame of crowned heads – by Alexander Sokurov, as Moloch (1999), Taurus (2001) and The Sun (2005). But, despite all this variety, the way this idea of king resurfaces in Ben Tweddell's vigorous and dynamic novelette, A Crown of Dusk And Sorrow sounds incredibly fresh, an extraordinarily beautiful book (more on that later) by Mount Abraxas from Bucharest. Tweddell's novelette, animated by the royal ferocity that is in its essence, seems to encompass a range of potential notions and concepts with a depth that is at the same time minimalist and complex, demonstrating an extreme mastery in the art of the novelette, which is the art of synthesis. Set in a terrible time of promises and disgrace – the 1930s –, in this strange English countryside that was the delight of Arthur Machen, we follow Daniel Turner's discoveries around a book in his library, a gem studied with a "friend" who suddenly appears in his life, Jacob Bartholomew. They search for revealing passages about a strange and mystical figure from the 18th century. But that search soon jumps from books to trails in the darkest forests imaginable. At this point, the plot, which provides this visionary and poetic contemplation of the nature's empire – following somehow Machen and Blackwood – got several twists and turns, in addition to sinuous transformations. There are bibliographical investigations and premonitory dreams, social celebrations shaken by dark presences and the glimpse of amazing, venerable shadows. The crown of the title appears in these glimpses, but the plot never loses its intensity, the strength of its grip. Ben Tweddell is an author who, since his first novel released by Mount Abraxas, The Dance of Abraxas, demonstrates an obsession with leitmotifs related to persecution/flight (which eventually become interchangeable roles) and accommodation/transformation (processes that occur through visionary interactions and breathtaking transfigurations). Thus, his personal approach to the royal theme is traversed by a phantasmagoria of persecution, almost a revision of the myth of "wild hunt" in new transcendent terms – the solitude of power becomes palpable, and the ruin is much more effective than any metaphor. For he is an author who cultivates a literature as dark as it is ecstatic, as brutal as it is entrancing. The Mount Abraxas edition, by the "Isolationnist Publisher" from Bucharest, is a masterpiece in more ways than one. The flow of text on the page, following the old maxim of William Morris (for a book with a truly good reading, the margin space and the text area should be in a balance as perfect as possible) creates an effect that we can only call cinematographic, and that we have already detected and highlighted in other books by the same publisher. It is the most perfect demonstration of the differences between digital and printed books, and the superiority of the latter. On the other hand, John Caple's paintings, on the cover and inside of the book, are superb, translating with particular intensity the understanding that lighting, of any kind, results not only in an essential discovery, but in the death of a human part in any person as a force generating a gradual departure from the society of the living, in search of the endless domains of Nature. His images are charged with an esoteric symbolism not distant from that of De Chirico’s one: isolated hieratic figures, contemplating the dark desolation of nature around that expands through tentative structures vaguely similar to branches and boughs. Mount Abraxas is a publisher known for the short run of its incredible books. This will have the same fate and could turn into something like the fragment of a nightmare, or an amazing but vague vision in the breadth of the human mind. Do not miss the opportunity if, in the decades to come, you find a copy of this gem in a small book dealer, lost inside some unknown city... More information on the book: [email protected]. Photos by Dan Ghetu.

The beginning of Kierkegaard's Fear and Trembling is well known - because the Danish philosopher “did not even understand Hebrew”, at least not enough for the intended exegesis, he repeats four times the narrative of Abraham's Sacrifice. These four brief reruns are made before a panegyric in honor of the biblical patriarch, famous for nearly killing his own son, Isaac. Perhaps the obsessive repetition of this narrative, of the biblical suspense about Isaac's potential death, of his murder by his father, points to a terrible doubt Kierkegaard felt in the abyss of faith: was Abraham's vision true? Would it not be an illusion of the senses?

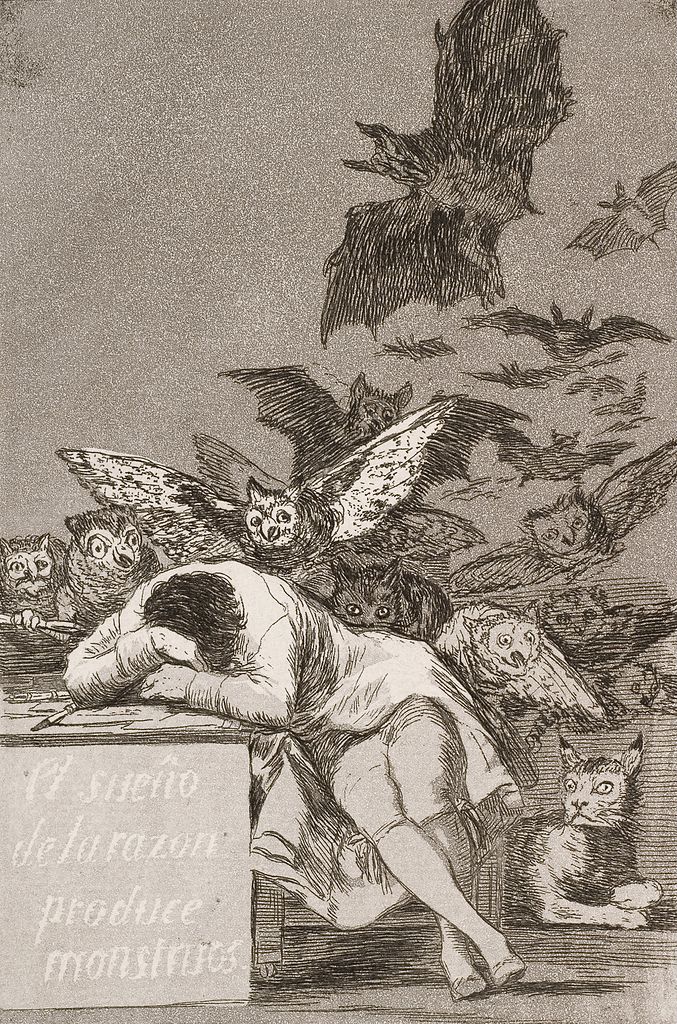

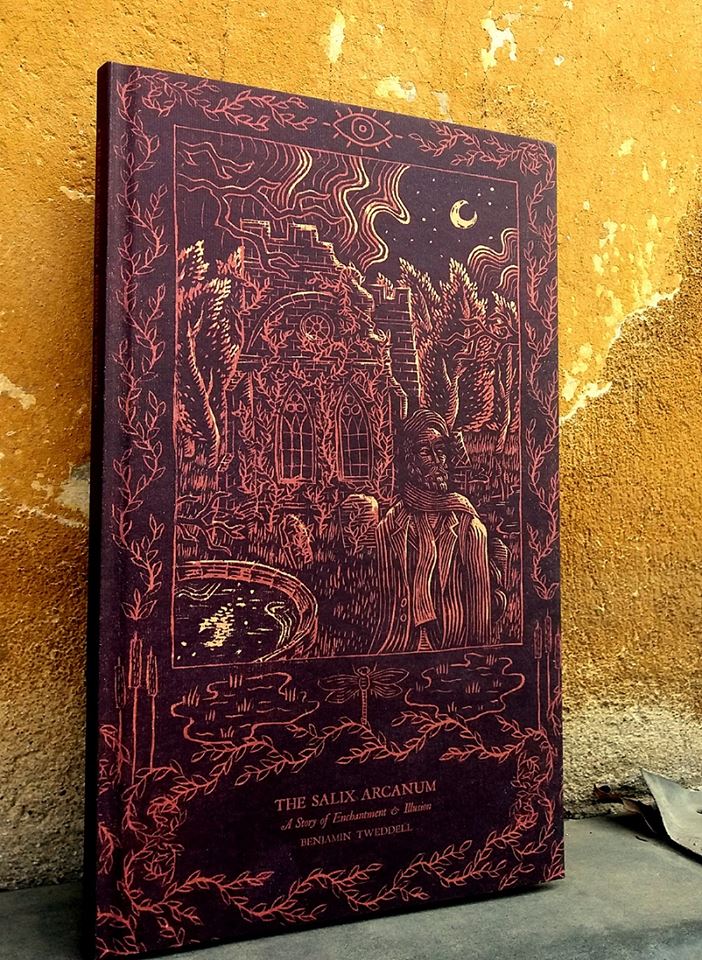

But there is something even worse, a terrible nightmare for the prophet, for the visionary: what if such a bloody holocaust was not inspired by the Almighty God, but the result of a diabolical chimera, a misperception of the signs in the hallucinatory reality, or a terribly mistaken caused by a persistent illusion? In this case, the founding prophet would become a mere murderer; and a perverse one, perhaps, willing to savor from his crime not just the justification for belief, but some unnameable pleasure. It is, after all, the same doubt experienced by all those blessed or cursed (both options are equally possible) by the possibility of living in the peculiar visionary universe. And the ambiguity of this blessing / curse that is at the heart of one of the most extraordinary narratives of 2019, Benjamin Tweddle's novelette Sermons In a House of Grief, published by Mount Abraxas – a veritable competitor for the best book of 2019 and pioneering work in treating this universe at the same time so concrete and so ghostly, the visionary sphere. Sermons is one of the truest works about what we might call the "visionary sphere" – by and large a very strange and complex phenomenon, difficult to describe in deep meaning layers or completely understand. Sometimes approached within the limits of research and prophylaxis of mental illness, at other times it is evoked in anthropological treatises. Projected on the mystical exegesis but also on the more tactile descriptions of the mental asylums, the visionary sphere arises from the short circuit between the usual perception of reality captured by our senses with a transfiguration brought about by projected elements of our mind, but with transformative new meanings with the merging of these usual elements. Tweddle seems fascinated by everything about the transformations wrought by the visionary sphere, and this is very clear in his first two novels, The Dance of Abraxas (2018) and The Salix Arcanum (2019). But in Sermons, the construction is both delicate – working every possible detail, such as the aural and tactile effects of visionary activity, and the leap that often exists between the conscious mind and the visionary state – and intricate because the visionary sphere of Leo and Matthias (both protagonists) seems to require considerable interactive effort from the characters which is soon transferred to the reader. For the visions inspired, or rather aroused, by the leader of the "Kartanoist" sect, Alma Kartano, seem to require a reading based on a threefold, apparently contradictory approach: meditative, interpretive, and transformative. Thus, there is a perpetual doubt about the validity (the question of veracity was ironically solved with the evocation by the plot of the The Wicker Man movie) of the visions in the characters perspetive; even at the end, when everything seems to indicate a definitive and final leap. This imaginative construction is original within the long tradition of visionary literature from Swedenborg or even earlier, with Master Eckhardt; and this originality makes Tweddle one of the best kept secrets of contemporary literature. The book was produced by Mount Abraxas of Bucharest and the aftermath, as usual, is phenomenal. The mystery presented by both the cover and dust jacket, the large format (as a picture book or, as I often imagine, a cinematographic book) the neat typography that makes reading smooth – all here indicates extreme care and refinement. The black and gold of the cover seems to dialogue with the sober internal photos that evoke the Kartaonist congregation. In fact, it is the Finnish band Mansion in such photos, whose strongly heretically songs are reconstructed narratively by Tweddle, who creates a plot-synthesis for the band's music and visual universe. But that, after all, matters little. To enjoy this novel is enough an imaginative plunge into the synaesthetic festival that is the essence of this veritable magnus opus in visionary literature field. El sueño de la razón, an engraving by Goya. There are some quotes so well known that their interpretation becomes very close to its own formulation – a more or less fixed interpretation, like common sense itself. Thus, the well-known phrase that Goya used in one of his best-known engravings (at No. 43 of Los Caprichos), "The sleep of reason produces monsters", is simply a recognized thought formulaic expression. The speculative dimension is lost, and we have only the premonitory aspects – we need to prevent reason from sleeping, or dreaming, and so we simply avoid the emergence of monsters (in political terms, probably). But if, by a brief speculative (and narrative) exercise, we ignore the prescribed notion of premonition? And if we allowed reason to sleep and dream? A reason with a specific core – historical, social, civilizational. What would happen? What images would the dreams and nightmares of this apparently autonomous reason produce? I believe something very close to that evoked in the fiction of Karim Ghahwagi, especially in this small breviary that is Children of the Crimson Sun, published by Egaeus Press. In the two narratives contained of the book, there is a visible, almost obsessive dedication of history, following the accurate evocation of past events. In the first tale, which borrows title to the book, we have a doctor who tries to help a girl, victim of astonishing ecstatic states. In the second tale, entitled "A Haunting in Miniature," a woman makes an investigation into strange supernatural phantasm in a group of Napoleonic Wars aficionados, making gruesome findings. In both tales, we have powerful historical facts moving to the background, like an amazing shadowplay. In the foreground, there are the so called “minor” events that flow in a dynamic of mutation, change, inconstancy – something that would the happiness of Heraclitus. But these events staged in the limelight are, in turn, petty, seemingly distant from the historical relevance of the great facts and narratives. As in a nightmare, the monster that emerges from the sleep of Historical Reason that is the focus of Karim, we have fragments, daily and prosaic details that are transfigured into a powerful and grim narrative. The logic of mutations in the two tales, thus reveals itself as the threads of a dream, a perpetual dreamlike activity, which our author chooses not to suppress but to elaborate in the most sophisticated way possible. The title story, in fact, made me think of the idea of vicious circle and Pierre Klossowski's strange philosophical novel, The Baphomet, but in a different pitch – very peculiar and far from philosophical experimentation imagined by Klossowski. The edition of Egaeus Press, in turn, is a exquisite beauty object, part of the collection Keynote Editions, with all its gold, its appearance of prayers breviary. A unique book, no doubt. And following an exclusive interview with the author. Regarding the two narratives of the book Children of the Crimson Sun, I realize that both work not so much with the History of great and main events (which nevertheless remains in the two plots as a background phantasmagoria). In both "Children of the Crimson Sun" and "A Haunting in Miniature", we have at the center of the stage the history of minor events, of hidden or secondary traditions, of tragedies whose metaphysical dimension often exceeds the apparently banal limits of the facts narrated. Talk a little about your methodology of approach to History and the story building on that curiously smaller, but not less effective, scale. I think that the protagonists in both novellas, ‘Children of the Crimson Sun’, and ‘A Haunting in Miniature’ are outsiders to some extent, while having certain profound connections to the cultures and traditions in which their stories unfold. Sometimes they are trapped and disadvantaged by the circumstances they find themselves in, other times their distinct perspectives lends them certain advantages – for good or ill. While both stories take place in particular historical settings and milieus, both protagonists often navigate, or mine, and investigate certain spaces or narrative cracks in the status quo of the stories and their settings. I think both Martina Voleron and Izabel Jelinek share certain existential dilemmas too; they both profoundly adhere to the tenets of their situations, and paradoxically also find themselves to be in conflict with them, especially when their intentions are benign, or when they seek to disentangle some mystery, or attain some form of enlightenment, for themselves- or for the communities in which they themselves, are part. I think therefore, that one historical approach, in employing a vast sort of canvas, can also be investigated in miniature, sometimes through a single character, or via the examination of a particular group of individuals, and perhaps from a slightly different perspective, in the hope of attaining some additional clarity in what is often a complex historical or metaphysical dilemma or situation . In the second novella, ‘A Haunting in Miniature,’ the protagonist, a priest of the Moravian Church, is investigating a series of hauntings in a small village in the Czech Republic. The story in part concerns a community of eccentric ‘old –school’ miniature painters and gamers, particularly interested in the Napoleonic period. In a sense they seem to want to sustain a certain coda, or even resurrect notions intimately connected to reenactment – and their art form by extension; this gives rise to all sorts of specters, locally, and perhaps in a wider context. Perhaps looking at something in miniature, as a synecdoche of a larger canvas, might help in certain circumstances; it might also prove entirely myopic for certain psychological reasons etc. I suppose both novellas deal with certain juxtapositions of belief systems, sometimes divorced from the sequential temporality in which they developed, often by the intrusion of the dark fantastic, or all too human agency. The power of the images in the two narratives are impressive. The cave scene in the first one or the presentation of the different types of enthusiasts in Napoleonic wars simulations are extraordinary – so complex that they seem to throw the reader into a kind of interpretative vertigo. How do you build such images; was it a slow, layered process, or did they emerge as ghosts and visions from your mind? Thank you for saying that. I had attempted to write the first novella, ‘Children of the Crimson Sun’, almost ten years ago, and wasn’t able to do it. I tried again about five years later, and found it utterly overwhelming and all but impossible. I cannot entirely remember any longer which images arose at what point, but the first draft of the first half of the story was written while visiting Tripoli, Libya, and I recall writing the story each morning while on holiday and hearing the sound of the call to prayer from a nearby mosque at the time. The latter half of the images in the story are much more recent and have certain connections to a horror story I wrote called Horrill Hill, which appeared in a Cioran anthology, and images in my novella Europa, an homage to William Blake and Mikhail Bulgakov. While I am quite comfortable with the technical aspects of say photography, to understand things like f-stops, shutter speeds, image composition etc, the ‘exposure’ of inner images is an utter mystery to me, and that in part has inspired the writing. Some images are artifacts of gleaned things buried in memory and the subconscious to resurface, some sort of synthesis I suppose, while others simply just seem to make themselves present, and I guess that part of the writing process is also an attempt to understand, or decode some of them. As regards to my approach in the first novella ‘Children of the Crimson Sun’, I spent the formative years of my childhood in Malta. I lived there from the age of six until I was sixteen, often spending summers and some Christmases in Denmark. I grew up surrounded by the buildings and fortifications of the Hospitaller Knights, and I remember visiting a megalithic temple in Tarxien to the south east of the island for the first time, and the caves of Ghar Dalam in Birzebbuga on a school trip when I was about eight or nine. I also remember seeing a recreation of the Great Siege of Malta in a museum-commissioned film, done entirely with silhouettes, fire and dramatic music and narration when I was about ten, that made a significant impression. I attended a private English Catholic all-boy’s school in that period, and had some teachers there who were nuns and priests. Those ancient caves and remaining fragments of megalithic temples, so prevalent on the islands, and the story of the Hospitaller Knights, and the Catholic faith, are certainly elements in the novella ‘Children of the Sun’, that I wanted to explore, and which then inspired further images. Malta is also particularly rich with local ghost stories and legends. It appears to be a kind of nexus, for various reasons. It has been about seventeen years since I was last in Malta, and I had opportunity to visit there again, just before I set to write the later chapters of the novella, but I decided that I wanted to describe any exterior elements of the islands from childhood memory, especially towards the conclusion of the story, in its more fantastical scenes. Also being a life-long miniature painter myself, I do enjoy the painting aspects of the hobby, and had opportunity to then introduce some of those elements into the setting of ‘A Haunting In Miniature’, into a sort of antiquarian ghost story. The novella "Children of the Crimson Sun" seems to have its center of gravity in the notion of mutation. The character's gender shift, for example, between pages 24 and 25, happened so suddenly that, in the eyes of the reader, it emerges at the same time as a rupture and as a possible event in the fluidity of the events of the plot. What was your inspiration for such a complex mutation approach? For nearly a decade I was unaware of the main character’s true nature. It was revealed to me only when it happened in the scene. I had written an earlier draft of the scene, where this moment had not occurred, and then wrote the next three chapters also. Then when I returned to that scene later to expand it, I was completely taken back when it happened - I remember just staring at that sentence with utter surprise, and then a substantial, subsequent section of the story became clearer to me, and allowed me to dare to attempt to finish the story. In retrospect there was already a certain ambiguous fantastical element introduced for the first time into the story in that scene, but then an additional sort of non-fantastical transformation also then occurred, and it then allowed me to understand that the novella was perhaps hovering between these two approaches in many different moments of the story, which I felt were interesting to explore. And certainly, there are other transitions, or mutations, or transformations in the story too, both physical, psychological and spiritual, and eventually even geographical/ architectural. There is certainly a preoccupation with particular religious iconographies, and certain religious tableaus in the Catholic tradition, of both the heavenly and infernal, that form part of the imagery of the story. I think also, that there is a certain ambiguity, in the moments of transformation or inversion, or a wavering, unsettled fluctuation between the one and the other. I had not considered the idea of rupture in the context of transformation or mutation, as a possible event in the fluidity of the plot, but you bringing it up here in context of the moment’s initial creation, or in the moment of mutation, and the effect it had on the rest of the story, is entirely persuasive, and an exiting thought to me. D'vorah's visionary state is quite peculiar: it is a elaborate synesthesia of colors and sounds, which the monks seek to reproduce literally, for the sonorities emitted by the child seem to defy the cognitive limits of consciousness. I wonder what the records of these monks would look like, what each one would contain. What is the immediate inspiration of that visionary state of your novella? I think it was interesting to attempt to map a certain belief system, that then found itself visited by a different sort of transcendent system, glimpsed in the inner eye of the beholder, perhaps spurred by an instigator of ambiguous origin. There is a certain dynamic montage, or polyphony of voices and sources, where perhaps something vaster than the sum of its parts is spurred into some sort of being, whether or not this is divine, or of some other origin, is perhaps part of the frisson of the story. I think that there is a certain ambiguity in the story in the relationship between muse or revelator or augur, and the perception of the receiver. I like the idea of a certain dynamic polyphony that the reader is presented with, an accumulation of glimpses that might draw the reader towards creating his or her own imagery in the mind. There is this notion of a kind of transference, or communicative non-verbal link, spurred by sound and perhaps by other energies, which then transform into certain sequences of words, language, images, architecture- all notions I find to be compulsively interesting to explore. In both novellas I was interested in having images fluctuate between their purely so-called ‘cinematic’ dimensions, and then for other images to function or manifest in a different sort of space. I guess in the story they are both manifested equally in the lexis of language, but then language can serve, or be employed, or have, certain other functions. To clarify this perhaps, I think sometimes of Arthur Danto’s aesthetics theory on the institutionalization of the art object. An object for example, can be so-called raised into the realm of ‘Art’, can be moved or taken from the ‘real world’ and repositioned into the ‘Art world’ because it is surrounded by language, that asserts that it is so. Language has an institutional function, it surrounds, or raises, or argues for placing that object into the ‘Art World’ -a different realm, or it adds a different, additional dimension to that object. You can be entirely critical of this, or find it partly persuasive, but it is interesting to explore in context of belief systems, applied to the understanding of how belief systems propagate, are understood, are psychologically digested, how they flower, and how they decay. As regards to the actual recording of the augur’s ambiguous condition, the manuscripts would not be unlike the illuminated sixteenth century Benedictine texts. Two texts are created on sheets of vellum at dusk and dawn by a rotating group of scribes, and the texts are then assembled into a single volume by Piranelli in the story. Abbot Jaccard believes that in the spirit of the child’s polyphony, the texts could be shuffled indefinitely, and thereby continuously create a sort of dynamic ‘shoal’ of meaning. There are small unresolved enigmas (at least in a linear and obvious way) in the plot of "Children of the Crimson Sun”: the destiny of the child's grandmother, the location of the ancient temples of Malta, etc. Has this non sequitur strategy of plot lines been deliberate, keeping gaps to widen the aura of mystery? Yes I think this deepens the sense of mystery, and also intensifies certain ambiguities which creates further disquiet. In the strands of the story that deal with metaphysical mystery, I like that certain things remain unresolved which the characters grapple with, which further highlights their struggles, navigating in a world where certain forces seem incomprehensible and strange. I think that the absence of both of the child’s mother and grandmother, creates a maternal vacuum, which then Martina is spurred to fulfill, while already navigating the precarious situation of her own identity and gender. I think we find a similar maternal vacuum in 'A Haunting in Miniature', just as the notions of parenthood are absent, missing or distorted. As regards the location of the ancient temples, there is a kind of transformation, or dare I say a transubstantiation from one physical form or realm and to another, bodily or an architectural one, that is not fully resolved. In the story "A Haunting in Miniature", there is the tension of a political commentary crossing, literally, hidden between the lines of the story; for example, when we are introduced to the group of "totalitarians" within the universe of enthusiasts in Napoleonic wars, when we discover the anarchist origin of the protagonist or when we see the strange name of this invisible antagonist (a kind of character that Tennessee Williams would love), “Kasper Von Hauser", so similar to Kaspar Hauser, the “Son of Europe”. How did this underlying comment arise, which seems so appropriate to the present days. The origins of Izabel Jelinek’s Moravian faith in the story reach back to the protests of Jan Hus, a Czech Protestant uprising that predates Martin Luther, both of which are actually predated by the protest of John Wycliff in England. So along one strand she has this anarchist impulse. There is a certain inversion going on, in that while she is a member of the clergy, a rather progressive one in this instance, certainly in the idea of women priests, gender equality, the role of women leaders in society etc, but there is a certain preservation of the status quo inherent in her position too, but she is certainly an anarchistic one. And she seems to equally navigate by empirical facts, as she navigates by indistinct. This is a characteristic that both women share in each novella. To my knowledge, there is no such term as the ‘Totalitarian’ miniature enthusiast in that particular hobby and art form, though its various subdivisions and separations are genuine. I just couldn’t help myself, in context of the other commentary going on in the story. And I like Werner Herzog’s Kasper Hauser film very much, though it’s a very long time since I’ve seen it. And I am a fan of all of Werner Herzog’s work incidentally. The Kasper Hauser connection is an interesting one I had not considered. I don’t recall how I came to the name, except for it to eventually be replaced by a different name. As regards any political commentary, I suppose I find it very difficult to grapple with those forces which attempt to separate us from each other, who wish to put one group of human beings above another, and who will go to great lengths to manufacture reasons for doing so. I think, perhaps naively, that we should certainly devote all resources to solving humanity’s problems all together. I find the idea of a toy, a miniature soldier painted in showy colors transubstantiated into a rather disturbing spectral appearance extraordinary. Has this finding come from any personal experience? Or maybe some specific reference? I think that miniatures have the same sort of disquieting qualities we associate with puppets, mannequins and dolls. They are inanimate objects that have the surface appearance of something living and human. In the case of miniatures, there is this additional intimate relationship to painting. I find that extremely interesting to explore. When I was about twelve I walked in on a group of English miniature enthusiasts, incidentally in Malta, who were playing a Napoleonic miniature wargame, as a demo to a small gathering in a gaming store. They struck me somehow as being ‘additionally’ dedicated gamers, as the prerequisites for playing their version of the wargame was much more time-consuming and financially demanding. All their miniatures were three times the size of regular miniatures, some were custom-cast in iron and lead, and the miniatures were painted in beautiful oils, as opposed to acrylics. There seemed to be a strict adherence to historical accuracy in the particular color and heraldry of the uniforms whenever a member of the public raised the issue. Everything about this group of dedicated men struck me at the time, as ‘next-level,’ and particularly fervent ‘enthusiasts,’ entirely enclosed in their own world. As regards to the second part of the question, about personal experience, that remains unresolved. It stems from a ten year period in Catholic boy’s school, which I have at present not dealt with yet in my writing, but I imagine I will explore further at some point in the future, if I am given the opportunity. Detail from Miracle of Saint Ignatius of Layola, by Peter Paul Reubens, 1620.

Abbey among Oak Trees, by Caspar David Friedrich (1809-10). In the beginning, before humanity, consciousness, perception, society and narrative, there was only the continuous flow of the cosmos, the slow geological dramas of displacements and accommodations, the infinite cycles of days and seasons, the perpetual entropic Nature. But suddenly, some primates discovered (or invented) the individual mind, with impulses that led in a direction different from those expected reactions to natural configurations. Then came the social organization. And later, the production of rituals that seemed to dialogue with the cosmic flows. Soon, the nomadic hordes began to settle, and the cities emerged – manifold in their shapes and sizes, from small, isolated villages to the megalopolises and gigantic conurbations that characterize the urban organizations of our present era. Cities are the human heritage par excellence – the living impressions (even when abandoned, in ruins) in the reality, attempts to postpone the uninterrupted flow of Nature. These scarred impressions in the fabric of planet Earth are sources of understandable and inexhaustible pride for mankind. Yet all this pride is not enough to appease the realization, sometimes painfully clear, that underneath these small and large landscapes built by men there are overwhelming forces – powerful rivers that no channel work can handle. The entire plot of Ben Tweddle's short novelette, The Salix Arcanum, revolves around the uncontrollable flows of nature, often invisible to our pedestrian and untrained senses. The author is cunning to maintain, obliquely ambivalent, the devastating forces of Nature – its origin, its unleashing, its purpose – perceived in an indirect and discontinuous way. The reader follows an obscure and ambiguous path, similar to that which the unfortunate protagonist also follows. For Mr. Godwin's path is the quest for understanding the strange world of a British rural community, seemingly ordinary. There are community parties, pubs frequented by religious and other gentlemen in the neighborhood, churches in ruins, marshes, woods and roads in the middle of nothing. But this is only the surface of placid, bucolic peace. At the subterranean thresholds there is the threat, the strangeness and, above all, an unknowable transcendence, which often seems pure, utter perdition. Ben Tweddle builds his metaphysical fantasy set in the British countryside with an extraordinary ability in the delicate construction of the visionary setting (gradually revealed and only accessible in all its glory at the end), a magnificent sensitivity to ambiguity, at least in the same baseline as Henry James. This extraordinary narrative, in turn, requires a kind of appropriate editorial and visual proposal. For it is a narrative where the visionary element and the contrast between perceptions produces a vertiginous effect on the reader – therefore, the design of the book would need to take all of this into account, since reading (in this particular case) was indeed an experience, not just the absorption of the immanent (or immaterial) content encoded in printed (or projected, or loaded) words. So the support needs to have another dimensionality - and this is guaranteed in the spectacular edition of Mount Abraxas. From the jacket – with a beautiful illustration by Matúš Ďurčík, reminiscent of the crude woodcut technique – to the typography and internal photos, everything in this edition was thought to evoke in the reader a unique visionary feeling in the reading process. The yellowing of the pages of the book immerses the reader into a 1970s film whose photograph was sepia-tone. The rhythm of the narrative, in which gradually the visionary landscape acquires more vivid and intricate traits, makes this yellowish world of the book something like a strange lysergic effect. Like the cathedrals in the wilderness, abandoned to Nature – which may be indifferent – from Casper David Friedrich's canvases, The Salix Arcanum will persist, a brief but intense glow (bright and dark at the same time) in the midst of the proliferation of life and death that is the entropic continuum of Nature. Photo by Dan Ghetu.

Non sequitur. There is a kind of delightful peculiarity in this Latin expression – perhaps because the language that expresses the the notion of non-continuity has the acrid sonority of an extinct language. Latin and Greek enunciations, in general, evoke (at least in me) this sense of speaking the language of the dead, as if through a complicated linguistic hallucination some living individual who expresses himself using Latin as a medium becomes in a talking, walking corpse. And since we are dealing with linguistic hallucination and non-sequitur, nothing is more appropriate than dealing with The Metapheromenoi, Brendan Connell's spectacular novel, recently released in sumptuous editing by Mount Abraxas. But what is The Metapheromenoi (literally, "The Transported Ones")? Well, the first page of the Mount Abraxas edition provides a clue to the core of the narrative: "A Novel of Degeneracy and Dope." It is a fragmentary journey through different forms of distortion of the usual perspectives, which make mimetic shadow of reality palatable to its occasional visitor, the reader. Each of the segments of the novel (called "Dyserotes”, literally "the unfortunate”, the first in The Metapheromenoi series) seems to follow the long non sequitur path, but there is something like a unifying principle in all segments: the mimetic reality of reading is slowly and subtly unraveling, so the fabric employed to unify fantasy and make it an experience close to reality can no longer sustain the tension that should be minimized to a casual reading, not haunted by the fragmentary perception of the whole. It is an effect remarkably close to hallucination, natural or drug induced; The Metapheromenoi, in this sense, is one of the most lysergic experiences ever conceived in narrative terms. But it is much more than that; there is a profound irony throughout the book. This irony is firmly, programmatically established in another of the initial paratexts, this time the dedication: "May the filth within these pages provide you with nourishment, so that you may twelve and dream away your farcical resentment." Although not as good as the dedication of Connell at the beginning of Cannibals of West Papua, such fierce note makes clear the ironic, strategic operations in the hallucinatory fields evoked by fragmentation, by nightmare images, by breaking expectations, by stylistic disarticulation, by confrontation of forms (drama, scripting for film treatment, vignette, conte cruel, poetry). It is a narcotic text streams (expressionist, decadent, or perhaps degenerate), using by Greek expressions as titles – a method that, far from endowing the work with snobbish exhibitionism, serve to carving new scars of eerie evocation, as a dead language spoken by the living person. On the other hand, we must highlight the editorial work of Mount Abraxas. Imposing, as usual, though opting in this case for dominant soft pink tones – faint colors, whose contrast with narrative decadent style establishes a kind of very welcome visual paradox. It would be excessive if the book's layout followed an overly dreary aesthetic principle. And the volume format, following the pattern of the latest editions of Mount Abraxas, is magnificent. It's like reading a short novel on a movie screen – the breadth of the margins, the size of the font on each page, seems to allow the imagination to expand itself to the taste of the images constructed by the narrative. And in the case of The Metapheromenoi, a novel full of disconcerting images, such an editorial solution is an amazing achievement. Photos by Dan Ghetu. I wonder how the land of Prester John would be in my dreams – perhaps, it would be a territory where milk and honey would flow from the earth. Or, on the contrary, an arid place, in which only the tears would serve to soften the stones. No matter: in my imagination, the possibilities are endless, contradictory, simultaneous. However, this imagined territory needs a map: this map should be a thematic hotel room, in which the borders of Prestes John’s country appear delimited in their physical, political, artistic, and social aspect. In this hotel room, I can begin the unstable rituals for the destruction of this concrete, dull world, which must be gradually replaced by that, wild, that exists only in the impossible continuity of the imagination. Damian Murphy's novels The Academy Outside of Ingolstadt and Abyssinia with its elegant structure, extraordinary images, fascinating characters and situations, not only offers us a remarkable narrative but the powerful resonance of a ritual, unknown and exquisite.Both books deals with geography – an exquisite geoscience, vague, starting from the subjective perception of a seemingly limited space but soon expands to much larger dimensions. The strange locations of both novels becomes, by complex processes of analogy and symbolic perception, in Europe and them, by a new metamorphosis, a scenery that could be, perhaps, our whole universe. In the book books, there are long, ritualistic and initiatory processes, a series of occult, hermetic meanings arise in denser layers. Novels that the spirits of Gustav Meyrink, Bruno Schultz or Franz Kafka would applaud – wherever they may be. Below, two brief interviews with the author about these unique narratives. Photo taken from the Ziesings website. On The Academy Outside of Ingolstadt. 1) What would be the origin of this extraordinary conception of his academy, a teaching institution so peculiar as that outlined in the novel. During the reading, I thought of the many schools, background of so many narratives – for some obscure reason, her academy of Ingolstadt reminded me of the women's school of the book (by Joan Lindsey) and the film (by Peter Weir) Picnic at Hanging Rock. But in any case, your academy has so many unique characteristics that it would be interesting to know the details of its elaboration. There are two teaching institutions described in the book—The Academy and The Institute. Both of these are partly based on my experiences living and working with the administrators of an esoteric order, but also on Gurdjieff’s Fontainebleau Priory and the boy’s academies imagined by William S. Burroughs. The Benjamenta Institute from Robert Walser’s Jakob von Gunten was certainly an influence, as was the Gormenghast of Mervyn Peake. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the school from Picnic at Hanging Rock unconsciously comprised part of The Academy. I’m quite a fan of both the book and the film and am almost kind of surprised that it didn’t occur to me to deliberately include elements from that institution in my own. I can only imagine that it unconsciously influenced the girl’s school described in the red notebook. The spirit of Kafka looms over the text as well, although, as with so many of my influences, the message contained within the book is very much the opposite of that of his work. 2) A visionary aspect is quite evident throughout the structure of his novel. But these are carefully structured visions, perhaps employing some method of conception such as that imagined by William Butler Yeats in his treatise on the subject entitled A Vision. In this sense, talk a little about creating the visions that drive the characters in your book. There’s a very particular mystery at the heart of the story which is never defined directly. It’s indicated in almost every part of the story, including some of the most seemingly trivial details. I don’t know if I could possibly articulate it in a purely rational way—some ideas need to be veiled in order to find expression. It took writing the entire book for me to elaborate it. The structure of the more enigmatic sequences in the narrative refer back to this mystery. This is especially true of the string puppet performance that takes place in the Institute. The vision that unfolds at the beginning of the book arises as a sort of warning for the main character. The second world war approaches, and the character is in very real danger. The Academy seems to stand entirely outside of the shifting tides of European power, and can serve him as a stronghold in which to wait out the coming conflagration. He also needs to return to the school to confront the ordeal that he passed through there in his youth. The school itself, so the impression is given, is endowed with a sort of sentience. If Fräulein Weiss is to be believed, it stands as the repository for the surviving fragments of a lost tradition. It’s reasonable to assume that the intelligence behind the institution remains in contact in some way with its former members. 3) There exists in this book, as in several of your narratives, the book / manuscript found, which structures the vivid unfolding of the plot. But the diary discovered in The Academy Outside of Ingolstadt this scheme is much more complex. From whence came the conception of the red diary and its rich gallery of rituals and characters. Initially, I wanted to explore some of the methods used in the teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff (which themselves provided a certain amount of inspiration for the working methods my own former teacher). Herr Schwarz is almost entirely based on that particular figure. The almost unfathomable depths of Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson, Gurdjieff’s unwieldy masterpiece, provided some inspiration, but only in the most incidental and oblique way. Some of the content in the journal came directly out of dreams. The two schools—the Academy in the main part of the narrative, and the Institute which is described in the journal—mirror and oppose each other in several ways, and are connected by numerous threads that wind their way through both sides of the story. The journal sections contain hidden keys to the non-journal sections, and vice-versa. Of course, an explicit connection between the two organizations is revealed at some point in the book—but then, can Franz be certain that this is genuine? I think it’s made clear that The Academy is not above making use of outright deception, even betrayal, if the administrators think this will further its teachings. There’s a certain amorality at play. 4) The structure of the academy/institute, with its intuitive learning scheme based on the discovery of symbolic elements (the relics) and on growing threats that need a kind of thought that is both elaborate and intuitive. It is a formulation that makes this entity, the academy, extremely alive, throbbing. What is the path to the elaboration of such a pedagogical structure? What is your inspiration in this regard? The escalating severity of the lesson types given in The Academy reflect, on the one hand, the full range of initiatory ordeals presented to the aspirant on the path of occult development, and, on the other, the perilous nature of some of the work undergone at the hands of my teachers. The most profound changes often come about as a result of crisis. This is definitely the case with the main character in the story, in whom a crisis of a somewhat drastic nature is deliberately induced. Photo by Dan Ghetu, at Ex Occidente website. On Abyssinia.

1) At the beginning of the book, there are a reference of three films, obviously fundamental in its composition. In this sense, Abyssinia was thought in cinematographic terms from the scratch – perhaps, as a script for a film, a narrative with visual elements? Is it possible to say that the powerful images that appear in the plot would have originated in this cinematographic sense? The original impetus for the story came not from any of the three films listed at the beginning of the book (Altman’s Three Women, Chabrol’s Les Biches, and Bergman’s Persona), but from the film version of Destroy, She Said by Marguerite Duras. As the narrative developed, the atmosphere gradually drifted more toward that of the three above-mentioned films. I was definitely thinking in terms of the feeling imparted by certain types of cinema when I was writing the book. Often, I’ll watch a single scene from a film over and over again, having become obsessed with the idea of somehow recreating the atmosphere in my writing. In this case, it was more the backdrop for the story, rather than the images themselves, that were inspired in this way. Things like the dream described by Dominik from the balcony of his hotel room, the war stories recounted by Karl Reginald, the images of The Apostate and his wife—these all came from other sources, while the world that they existed in was shaped in accordance with the impressions I received from these films. 2) I think it is curious that in the short list of films mentioned, there is no Last Year at Marienbad (1961), the famous collaboration between Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet. There are some elements in Abyssinia more or less close to the creation of Resnais / Robbe-Grillet, notably the labyrinthine hotel as a backdrop, although with very different results, techniques and narrative strategies. Was such a film an indirect influence, an inspiration by elective affinity to your novel? Last Year at Marienbad is very much a favorite of mine. I’ve seen it so many times that I suspect it casts its shadow over everything I write. 3) There is, in the novel, a fascinating shadowplay between the animate and the inanimate, the active and the inactive, the simulacrum and the real living being. What artifices did you use to create this universe? How did the idea of this dizzying game of projections and mirrors come about? Part of that, especially in the case of doll that Celia manipulates and talks for throughout the story, must have come from the way in which the characters of a story come alive for me in the process of writing. No matter how many times this happens, it surprises me in every instance. The characters of any given piece are at once part of myself and have a life of their own. As they arise, take form, unfold and develop, they tend to take over a portion of my personality. So much so that I’ve actually had to learn how to allow this to happen without letting it affect my outward behavior in inappropriate ways. It’s been said that when an artist reaches a certain level of maturity, they become capable of creating something that’s more than a mere expression of themselves. On the other hand, Jean Cocteau, in his Testament of Orpheus, shows himself attempting to sketch an image of a rose, and instead ends up, to his great frustration, sketching an image of himself. Well, if Jean Cocteau, toward the end of his life, still found himself falling into that trap, I won’t be too hard on myself for succumbing to the same tendency. On the other hand, while everything I write is in a sense a self-portrait, in another sense there’s a different element that arises in the text as well, something that I can’t entirely understand. The same is true with Celia and Karl Reginald—on the one hand, the doll is a projection of something in her personality, part of which is known to her and part of which reveals itself only through his monologues, and yet there’s clearly something else as well. Karl Reginald is at least partly endowed with a life of his own that lies completely outside of his controller. As for how the complex structure within the story was created—I don’t really know how that happens, to be honest. There’s almost always a hidden structure that underlies my stories and which keeps all of the different elements from falling into incoherency. Sometimes this structure is present from the beginning, while at other times, as with Abyssinia, it reveals itself to me a little at a time. Colonel Olcott’s book of maxims reveals the barest outlines of this particular structure, while Karl Reginald’s remembrances (along with several other elements of the narrative) cast it into a different light. Parts of it remain unknown to the reader. I like to think that it can be caught sight of in completion by the intuition alone. 4) In Abyssinia, the reader is constantly placed in a situation in which it is difficult to apprehend the changes in the fluid territory between dream, memory, imagination and perceived reality. This ambivalent atmosphere allows the emergence of characters with powerful symbolic meaning, such as the Apostate – enigmatic, threatening, hieratic. How was the development of this character and the mythic-ritualistic effects in the novel? The figures of The Apostate and his wife made themselves known to me very strongly right at the beginning of the process of writing the story. I didn’t fully understand them until well past the halfway point. By the time I’d finished the piece, I’d written somewhat of a treatise (in my private notes) pertaining to their mythological significance. Still they seem very real to me—they’re larger than life, almost as if I’d encountered them myself in exactly the same way as did Petra. Of course, they’re meant to be personifications of undying principles with which, in very different forms, I have quite a bit of familiarity. Karl Reginald, on the other hand, was loosely (though not too loosely) drawn from a set of real-life experiences. 5) Do you intend, in the future, to resume the fascinating characters and unique universe of Abyssinia? I must say that leaving them behind after the reading experience was somewhat hard. I would be reluctant to return to a character I’ve already created—there are so many new voices that want to have their chance to speak. The feeling of not wanting to let go of a character or set of characters is precisely as intended. Hopefully, they’ll live on in the reader’s mind and continue to reveal things that I would not be capable of revealing myself. Photos by Claus Laufenberg. One of the most vertiginous and extraordinary film panels of the historical past is undoubtedly Andrei Rublev (1966), by Andrei Tarkovsky. Rublev was a Russian icon painter in the fifteenth century, an enigmatic and mysterious figure, whose artistic production was almost entirely lost (less than twenty works attributed to him), in an ebullient and ferocious historical background. Tarkovsky's film embraces this effervescence and ferocity, and instead of focusing the narrative on an artist whose biography seems almost unknown, opts for the composition of genetic historical panels, culminating in a beautiful, poetic and touching narrative of the building of a bell for a church. More than the (if imaginary) biography of a genius, Andrei Rublev is a deep reflection on Art, History, Barbarism and the Creative Will, essential to the human being. It is curious and even appalling how, after finishing reading Brian Howell's astounding novel, The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius, it was precisely from Tarkovsky's film that my wandering mind remembered. No other historical novels appeared, but the images of the Russian painter, lost in an apocalyptic landscape came out of a nightmare, a historical one. For Howell's masterpiece – probably one of the best novels of the early twenty-first century – is also centered on a painter, Jan Torrentius, a man of succinct, mysterious biography and minimal surviving production – practically reduced to a single absolutely spectacular painting. And if the multiple layers present in the intricate statements that make up the plot suggest multiple and rich interpretive paths, I especially hold Howell's affectionate homage to the human dream of cinema and photography, this ancient desire to freeze time in an instant of eternity. The edition of the book, by Zagava, is simply spectacular and deserves, in the future, essays and articles about its paths between a first abridged publication and the current, complete version. Below, the video and written interview of Brian Howell regarding his fascinating and baroque narrative about painting, heresy, secret societies, images, intrincated artistic visions, dreams and the fortuitous nature of truth. 1) Your novel was first published in 2014 under the title The Stream and the Torrent, as a novel of reasonable but apparently conventional extension, with its division into three chapters (the title of the second, "Ex Anglia reversus", incidentally , Is great). But the final version of the novel is much more intricate: there are six (or three) books and the chapters division has multiple presentations and introductory essays that clearly define some narrative options, as well as a chapters division as statements. How was the development of your book: did it come in a more or less definite format or did you develop the ideas of it conformed more and more complex? How was the development of your book: did it come in a more or less definitive format, or did you develop his ideas over a period of time, to its final form? The basic shape of the novel was always set as consisting of five or six sections, with the last sixth section an option. Originally, each statement, solicited by Huygens as a kind of collective portrait of Torrentius, was preceded by a prologue, but as I got more and more views on the novel as a whole, these prologues became subsumed into the sections proper. The content of the prologues was basically still there. These prologues for the statements have to be distinguished from the Prefaces by Christiaan and Constantijn Huygens, which were there from the beginning, and the epilogue by Christiaan. The extra prologues just made it too busy and confusing. The above has to be separated to a certain from the way the book first appeared with Les editions de l’oubli/Zagava in 2014 under the title of The Stream and The Torrent: The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius and the Followers of the Rosy Cross: Vol. 1 had discussed with Dan Ghetu of Ex Occidente various permutations of the segments (statements) simply because he could not publish any one book over 50,000 words, as I understood it. So I made a decision to put the final segment by Torrentius at the beginning of Vol.1 along with what had always till then been the first two segments by Huygens and Drebbel. The problem was that these appeared without the prefaces by the father and son to give them any context. I think the reader is forced to read them as three floating, vaguely connected novellas about this character called Torrentius. It will not be until the complete The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius appears with the Table of Contents (available for people who already have Vol.1, too) that readers of Vol.1 will have any idea of the originally intended order (Huygens, Drebbel, Carleton, Elizabeth of Bohemia, Donne, and Torrentius)! Before this decision was made I think we came close to what was a good compromise in so far as Ex Occidente might have published four slim volumes (Vol.1: Huygens and Drebbel; Vol. 2: Carleton: Vol.3 Elizabeth and Donne; Vol.4: Torrentius. Combining Vol. 3 and 4. might have also been mooted). That would have kept the order but at the time I think I wasn’t sure how long the Torrentius segment was going to be and in the end it turned out to be very short. Either way, that idea would have represented the novel in the right order, as now the The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius does, finally. The latter is one of a number of permutations and ideas so I can’t say that any were set in stone before it came out in the Vol.1 incarnation. That said, the various permutation did not make a great difference to the fact that it was always one novel. The only variable in my mind was the idea that the Huygens section might be too slow so I always had the idea to put Torrentius’s segment at the front in the back of my mind, but in retrospect this was a bad idea and the idea of putting it in Vol.1 was basically my idea, and I regret that move. Luckily, Zagava have given me the chance to redress that mistake. 2) Still in the statements: it is a peculiar and intelligent strategy of fragmentation of the perspectives surrounding the mysteries involving the enigmatic Jan Torrentius. There is even something about it that reminds me, for example, of Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (as well as the two Ryonosuke Akutagawa short stories that were adapted by the Japanese director in his film). Would the foundation of this conception be more cinematographic or literary? How was the construction of this fragmented universe in varied perspectives? I was familiar with the film version of Rashomon but what was in my mind from the very beginning was Citizen Kane, but only in the most basic way, i.e. a portrait of a mysterious personality made up from different dramaticised accounts. I haven’t seen Citizen Kane for 20-30 years so I can’t say how similar or different it actually is in structure to The Curious Case. But certainly some narrative strands overlap, probably in the way they do in Rashomon. To me, the content of the story has always had a connection with cinema, but the execution is literary, if that makes sense. The whole idea of a prototype of photography, and therefore in an implied way, cinema, comes from the subject of how Torrentius is involved in a form of early photography. But when it comes to all of the historical characters who either knew him in reality or who I made know him fictionally, a great amount is based on their original writings, whether letters or poetry or any other kind of literary output. One big inspiration was always the letters of John Evelyn as a sort of ground layer for the style of the time, even though each historical character had their own linguistic style – and Evelyn comes a bit later in the century. I don’t know if what I have done with them is a pastiche or an imitation but it could never be a totally consistent pastiche because a really skilful pastiche or rendition of Donne’s writing would be (almost) unreadable to the modern reader. To that extent, I used some of his actual poetry and some verbatim excerpts from his sermon! If I was going for any effect, it was for the Jocobean/Carolian language of the time, which I love, but it sounds awkward to modern ears (if done perfectly!). There is also the fact that not all of the characters are writing in their original language. 3) The approximation between written and cinematographic narrative is far from being something innovative, but the fact is that the basis of this approach happens, in general, in view of a literary reproduction of the cinematographic montage. In Serge Eisenstein's Immoral Memories, for example, this type of experience is clearly manifested: Eisenstein's observations are driven from one topic to another, in a structural scheme that resembles the film (and poetic) structure based on parataxis, on the non-sequential logic, a kind of form usual in the film. But your The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius follows a much more visual principle – the illusion of the images is reflected in the fluidity of identity and the adventures of the characters. In constructing your narrative, have you taken into account this eventual opposition between montage / image, in the case of the cinematographic effects on the narrative? Or in evoking a kind of ancestral cinematographic technology, did the modus operandi of the moving-image perception of the Renaissance and the Baroque had some directly influence in your creation? I would say that the way I am trying to deal with this subject is more organic. I am attempting to take the various anecdotes about how people of the time – especially Constantijn Huygens and Drebbel – who experienced the camera obscura and were in a position to write about it reacted, and embellish that with imagination and fantasy. In some cases reports go as far back as Leonardo with respect to the camera obcura and as far as forward as Kepler and others. This is mixed in with the idea of the occult, magick, alchemy, and thaumaturgy, magic lanterns, and modern cinema. I was probably much more influenced by the work of Frances A. Yates’ speculative ideas about Elizabeth of Bohemia in The Rosicrucian Enlightenment than any other work. There is an example of a kind of cinema or live show seen by an audience in a dark room using a camera obscura or something similar, which I adapted in the dénouement to one of the sections. I think it’s based on fact but I have to go back and check but I think it’s feasible. There are too many to mention here but one type of pre-cinema, even though it’s anachronistic in the context of the 17th is the tableau vivant, as exemplified by a scene in the film Last Year in Marienbad. It is also a kind of contradiction here in the sense that the tableau vivant is a motionless recreation of a scene, say, from a recognisable painting which is ‘performed’ by living people in statuesque poses. And then it is filmed! But something of the atmosphere surrounding it sums up something of what I am trying to do in an earlier era. What is missing, of course, is the ability at that time to fix the image and certainly to reproduce motion chemically. So I used a kind of mixture of sleight-of-hand showmanship and possible scientific invention. 4) The novel approaches obliquely two parallel conceptual axes: the mechanisms that gave rise to cinema and photography (that is, means that surpass the pictorial representation as it was recognized and accepted in the time of Jan Torrentius); the secret societies and political conspiracies that shaped Europe since the sixteenth century. Considering that such a brilliant rapprochement of these two axis was deliberate, what would be its basis for such a development? Since the novel preserves the mystery of both strands, where would be the point of historical convergence? I would have to refer again to The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. I am going to claim that the idea of joining the speculations about Torrentius’s use of the camera obscura, including some of the wilder claims about how he used it (which to me implied he was used a proto-photographic device), to the idea that he was a Rosicrucian (still unproven) is mine, BUT Yates implies very heavily that there was a hidden movement to bring Elizabeth of Bohemia and her husband Frederick V of the Palatine to a position that would challenge that of the Holy Roman Empire and even a so-called ‘Reformation of the Whole Wide World’. Now, whether that revolution would have been all Protestant, I don’t know, but, combined with the tenets of the Rosicruicans, I think it is implied or I would at least have liked to imagine it as a pan-religious organisation embracing all religions of the time. Of course, we are in the realms of fantasy here, but Yates was a serious scholar, so, when you think of some of the unlikely organisations and philosophies that have come to transform history in the 20th century alone, it’s not totally unimaginable. We have to remember that this was a time when many secret societies of a utopian bent existed. They were Christian and peace-loving, as far as I can tell. 5) Your novel, in its dense and intricate structure, has an undeniable appeal not only visual – what would be natural because of the focus of the narrative – but even cinematographic, as already addressed in other questions above. And this appeal comes in both sensory and narrative terms: all the colorful paneling of European cities and courts of the time, the disputes of artists, the desperate search for aesthetic-technological innovations – these visual glimpses sharpen the reader's imagination. In that sense, would there be de facto plans for some sort of audiovisual adaptation? Or, would your novel have been thought for the audiovisual medium at some point in its development? Maybe strangely, I have not written this with a film or any kind of audiovisual adaptation in mind. I think it would be a hard task but definitely possible and ripe ground for an adaptation. I think any adaptor would have to decide for themselves where they stand with the character of Torrentius, whether they see him as a charlatan, a misunderstood libertine, a serious artist, or even a heretic. I think it’s fairly ambiguous in the book but possible to come out on one particular side. Once that is done, any director could have a great time with bringing to life the audio devices and magick that is on show in the boo, not least because the exact nature of the machines or projections are pretty ambiguous. I can’t imagine adapting it myself but I can’t help thinking of films like Nolan’s The Prestige or Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract. The audio version of the interview follows below. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed