|

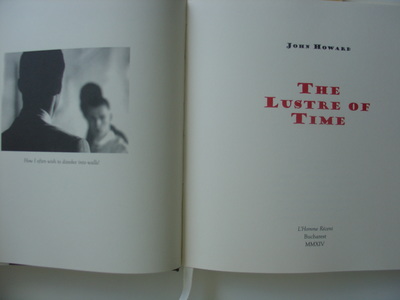

In a recent past, a very large History of the World seemed a good idea: authors like HG Wells sought audacious narrative synthesis of the multilayered historical process. The efforts were elegant or eventually reductionist in the task of extracting a logic in the History, a process that has certain essential disorder, as said Jean-Paul Sartre. In fact, a possible criticism about universal stories, perhaps the most striking critic, is precisely the approach of historical fact, because the universal historian appreciates the wonder facts and great names in a seemingly continuous line of progress. However, there is another History, populated by people and events unjustly ignored, remote or marginalized. This historical otherness, that is often not even known, emerges in a unique form in the works of John Howard. The marvelous fiction of Howard addresses fantastical phenomena and philosophical questions in the edges of our history and cognitive universe – sometimes in totally imaginary regions, as is the case of his most significant topographical creation, Steaua de Munte, a exhilarating region of imaginary Romania that can be visited in his latest novel, The Lustre of Time. Even the supernatural in Howard creations is subtle one, almost imperceptible – the uncertainty is the poetic weapon of John Howard in his antithesis of universal history, an imaginary history, unique and terrible.

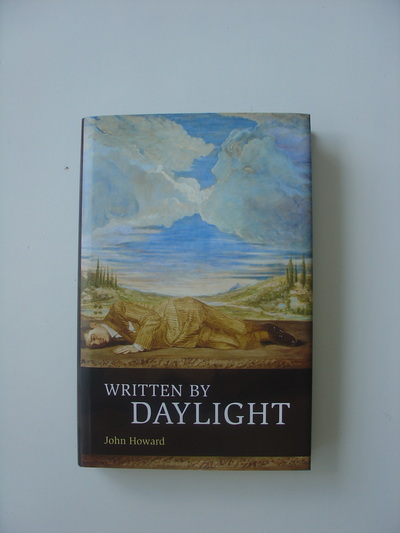

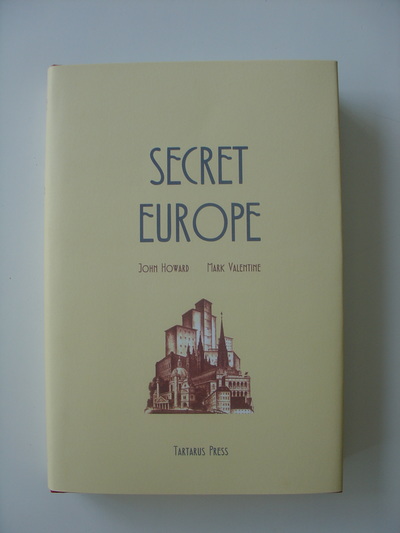

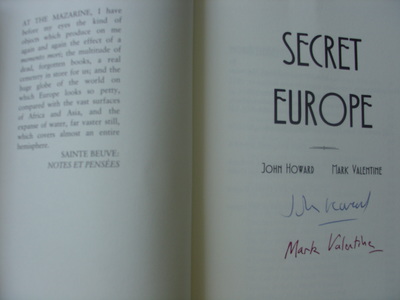

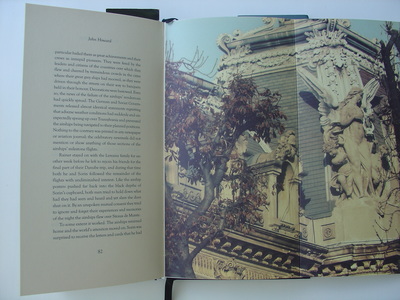

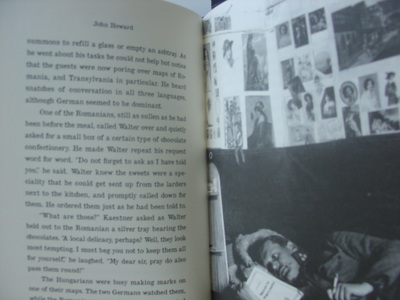

A very particular approach to urban topology, including the development of an entirely fictional town, Steaua de Munte, emerges in your works. This imaginary city is extraordinary, an entity that continuously develops itself over several short stories and novels, with its cafes, hotels, universities, hills, houses, buildings. It's an imaginary space equally or more extraordinary that William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County or Arkham by H. P. Lovecraft. So what would be the point of creating a fictional territory in such a distant place, covered in a peculiar picturesque mythology, Romania? What have been your sources and conceptual and imagery sources for the construction of Steaua de Munte? Modern Romanian history has interested me ever since I came across a contemporary account in John Gunther’s Inside Europe (1936, and subsequently much revised and reprinted). This was when I was still just a teenager and there seemed no reason for Communist rule behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ not to last for ever. I found Gunther’s portrait of the country as it had been nearly fifty years before my time to be utterly fascinating. Romanian politics were byzantine, Ruritanian, and murderous. And the country’s leaders – especially the flamboyant king, Carol II – seemed larger than life. John Gunther was an American newspaper reporter, a foreign correspondent in Europe for many years before and after World War II. He became one of those authors whose books I always look for. I have a shelf of them. I never forgot Gunther’s vivid and accurate summaries, and when Ceausescu and the other Communist leaders fell, it came as no great surprise to find their countries carrying on, in many ways, from where they had left off in the 1940s. There is so much in the histories of that part of Europe which seems almost operatic or something out of a television drama – if it had not been real, it could only be believed as fiction. But that is easy for an outsider such as me to say: these people were also responsible for ruining the lives of so many of their people. Fiction can examine the dark places – and should do. The opportunity to visit Romania came in 2009. The previous year Dan Ghetu’s Ex Occidente Press of Bucharest had published The Rite of Trebizond and Other Tales, a collection of stories mostly written in collaboration with Mark Valentine. Dan had read “The White Solander” – one of the tales of The Connoisseur that Mark and I had written together, and which had a Romanian background. Then Dan invited Mark and Jo Valentine and me to visit Romania. Dan and his wife were generous and painstaking hosts, driving us around much of the country in an exhilarating tour which nevertheless ended all too quickly and still left too many wonderful places unvisited. We crossed the mountains into Transylvania and stayed in the old cities of Sibiu and Sighisoara, and these were the main sources for my city of Steaua de Munte. But in most respects Steaua de Munte is a unique and special place, not dependent on anywhere else, and is what I, as sole proprietor, choose to make it – and remake it. Novels and series of stories set against a common background have always appealed to me, especially when the setting develops and changes, with various different aspects being revealed at various times, and yet which also leaves much to the reader’s imagination. Characters come and go (and families and relationships are vital) but the background scene, even when it changes, does provide a level of continuity against which new stories unfold and have consequences for the unwritten future. The protagonist of "The Fatal Vision" (the longest narrative of the book Cities and Thrones and Powers) and The Lustre of Time, Dr. Cristian Luca, embodies something of the archetypal figure: the modernist architect/urban planner acting as a demiurge, fighting world authoritarian and vulgar perceptions. This archetype has its own history, dense and multiform, and came even to the cinema through The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand's novel, adaptation directed by King Vidor in 1949. Luca was your personal view of this archetypal figure? What about the development of such character? Now I have to confess that I’ve never read The Fountainhead, nor seen the film – I must try and do so! Luca first appeared as something of a background character (although a pivotal one) in The Defeat of Grief, and I never planned on him appearing again. But he did! I never attempted to train as an architect – I wouldn’t have stood a chance – but I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in buildings and their creators (this also includes structures and engineering such as bridges and tunnels). As a teenager I found books on modern architecture, and was captivated by the architects’ visions. It was even more inspiring because they were being built: Brasilia, for example. Of course, there have been all sorts of problems and unintended consequences – but I have to respect, if not love, the soaring visions. I imagine Luca to have come alive to a vision of the future when he was a very young man. However, he had the intellectual ability to make something of himself, and also the social and political skills to navigate his way through minefields of academia and patronage. I do not intend Luca to be a ‘good’ man – in fact at times he has been a total bastard! But he does what he does in order to survive and remain true to his vision. This comes at a cost to himself and to those close to him. The highest success is only one step back from ruin and defeat. Hopefully Luca will return at some point. That man is a born survivor – he learns from experience! And he’s a genius. But as a human being he’s flawed, and certainly damaged. Some stories seem to generate characters who must work in the background, who influence and fix events, who wield power over others, but remain behind the scenes and in the shadows. They are the people who have to do things for other people because the other people can’t be seen to be involved. On the level of fiction I like these sorts of characters, and the ‘secret history’ of their worlds. They are not ‘nice’ or ‘good’ people – but they are as they are for a reason, just as people who take risks, hurt others, and cause damage have often themselves been hurt and damaged, somehow. Well-adjusted and contented people don’t make very interesting characters. In your narratives, the architecture (as a style, a form, a concept) becomes a exquisite element, not only related to the concrete spaces but also to the sensuous perception and physics of cities and their buildings, crossing the skin and bones in characters like Dr. Cristian Luca, mentioned in the previous question. Incidentally, there is in the novel The Lustre of Time a memorable passage, in which Luca declares his desire to dissolve himself, merging his atoms with the walls around. Where you located the origin of this personal and unique architectural approaching used in your stories? As I said, I came across modern architecture in books. But there was also the country I was growing up in. It was being built, or was still new. I’m too young to remember Harold Wilson’s 1963 speech in which – according to the internet – he said ‘In all our plans for the future, we are re-defining and we are re-stating our Socialism in terms of the scientific revolution. But that revolution cannot become a reality unless we are prepared to make far-reaching changes in economic and social attitudes which permeate our whole system of society. The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry.’ But I grew up in a country in which to some extent Wilson’s vision did get the chance to be worked out. The future was going to be brighter, cleaner, safer. Slums were being demolished and new housing built. In some places the ruins caused by World War II were finally being swept away – in London there was the Barbican scheme and Route XI. Sleek motorways crossed the country. Jet airliners like vast metal birds flew overhead, and I watched the Apollo missions on TV. Now we know that new solutions give rise to new problems, but to this child it seemed that only challenge and wonder was in store. I read comics and watched films and programmes on television which showed the marvellous buildings and world of the future, and I thought that one day I should see them and live in that world. Sometimes I feel that the bright future has been stolen, so perhaps I try to compensate for that loss in some of my stories. I consider specially outstanding your short-story “Twilight of the Airships”, a narrative based in a singular speculative concept whose climax, the “invisible battle” between the Soviet and Nazi airships, brought to my mind both the novel also populated with airships The War in the Air, by H. G. Wells and also certain Jorge Luis Borges tales as “El milagro secreto”. Why this approach to the airships as the plot defining form, in this particular case? However, your approach to the airship technology, far from conventional steampunk views, would be closer to scientific novels of H. G. Wells, Charles Hinton or J. H. Rosny? My interest in airships comes from childhood. Like most boys I was interested in mechanics and machines – the bigger the better. I had a Meccano set and lots of Lego bricks. I was never much interested in cars or trains (even steam trains) but I loved ships, aircraft, and rockets. I used to know how the various types of engine worked, how to recognise the different jet airliners and World War II planes, all that sort of thing. Sometimes our father used to bring home books for us that he’d bought, and on one occasion he gave me a book about airships – from balloons to the World War I Zeppelins to the great airships of the 1930s and the era that ended with the Hindenburg disaster. There were lots of pictures. (I wish I had that book now, but I must’ve given it away or lost it.) The thought of these majestic craft the size of ocean liners plying the skies in commerce and exploration still fascinates me. I’ve loved Wells’ work since first reading The Time Machine when I was ten or so. I only read The War in the Air fifteen years or so ago, and I expect it was in the back of my mind when I wrote “Twilight of the Airships”. There were also the real-life accounts by the crews of the German Zeppelin bombers and the British fighter pilots trying to shoot them down. My grandmother saw a Zeppelin shot down in flames over north London, and she had a postcard showing the smashed metal framework on the ground. Another confession – I don’t know Borges’ story at all. Another situation I should remedy. I am really not at all well-read! I realized a recurring interest (even obsessive, maybe) through your stories on maps and in the definition of borders. The greatest example of this interest is the novel “The Unfolding Map”, included in the Infra Noir collection, centered on the strange mystique of the borders redesign and reconfiguration, an operation that jump from paper to reality. Such interest would derive from European history? Or is a kind of experiment with the power of idea contrasted with the restrictions of material/political reality? Yes, I think my interest in boundaries and their changeability comes from being interested in European history, although my interest in European history probably only started getting serious after I’d discovered the concept that countries’ borders were not as stable as I might’ve thought. When I was thirteen or so I was bored during a school holiday. There wasn’t much to do where I grew up. I went to the town’s library, and then into the reference library, and for some reason took a historical atlas from the shelf. I remember taking it over to a table and sitting down – and then being plunged into a world of shifting frontiers, with empires rising and falling in tides of different colours washing across the pages as I turned them. I must’ve realised that this charted the passing of decades and centuries. Names that had persisted through the centuries would suddenly vanish and be replaced by new ones. It all illustrated to me from an early age that nothing lasts for ever. And of course I quickly found out that the European frontiers I saw in my parents’ atlas at home were extremely recent. If borders have changed in the past, they could do so in the future – and many in Europe did eventually undergo thorough change in the early 1990s. And it all happened surprisingly peacefully except for the terrible, unnecessary, break-up of Yugoslavia. I suppose the power of idea lies behind many such changes: nationalism and the desire of a certain group and/or its leaders to enforce views of itself based along ethnic, cultural, religious lines, for example. Changes of border are one of the outward signs of something else – and that is what can be fascinating to make fiction out of. Times of war and economic turmoil have often been accompanied (or followed) by great creativity, and ordinary people showing what is best in humanity. Of course, creativity can also be stifled from above during such times, and people show the worst aspects of human nature. But I think treating these sorts of themes in fiction, and including real events and people from history can allow new insights to be born from the new stories. Or we can be reminded about things we ought not to forget. Behind border changes, behind the reality of changing the names of cities and streets, behind banning a book or smashing an artefact, there is also the reality of human cost, human loss, human pain. And yet there can still be humour, the bearing and sharing of burdens, the creativity. It seems to me that most people will always try to defy and overcome restrictions, however that might be in their different situations. Fiction can show that. The uncanny or weird effect in your narratives is quite subtle, with a hard philosophical investment. The strangeness in your stories is a gradual aspect, unveiled momentarily and covered again – an effect achieved by the clever use of continuity fragmentation and changes of views in the plot. Tell me about the process of creating this conceptual strangeness/uncanny/weird which I believe should not be enjoyed by certain fans of hardcore supernatural horror. I don’t think I’m aware of any conscious process – it just happens (or fails to happen)! I write very much by instinct, and quite often begin a story with no real idea of how it will end. I find that the process of writing a story tends to generate what then gets included, more so than any notes and outlines I might prepare first. What I do know is that I like subtlety rather than ‘blood and guts’ – although there is a place for that in supernatural horror fiction. Whether it’s always accurate or not, I prefer to think in terms of the ‘numinous’ rather than the ‘supernatural’ – although when it comes down to it I don’t really mind what labels get added! One of the essential aspects of your narratives – even before any editorial treatment – is the elaborated imagery, sometimes evolving for a visionary formulation. It would be extraordinary to see some of your stories, such as “Out to Sea” and “The Waltz of Masks”, in movies and on television. What is your connection with the aesthetics and cinematic thought? Do you have any future projects for cinema or television? I do tend to think in pictures, and I think that’s one of the reasons I often begin a story with uncertainty as to how it will end. Or sometimes it’s the end or climax of the story (not always the same thing!) that occurs to me first, and it occurs in visual terms. Then I make a note of it and then try to work out a story which can include it. “The Waltz of Masks” was inspired in part by the great set-piece ballroom and party scenes in one of my favourite films, Oberst Redl (directed by István Szabó). These are gorgeous and magnificent, feasts for the eyes (as well as the mind – as the entire film is). I don’t seem to watch as many films as I once did, but the ones I really like I’ve seen so many times and still watch again and again that I feel I know them well – although they can still throw up surprises, which I like! No, I don’t have any plans for cinema or television projects, and they’re not things I’ve ever considered doing myself. But I would certainly be open to anyone who wishes to adapt or collaborate… Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). Below, some works by John Howard: Written By Daylight, Secret Europe, Cities and Thrones and Powers, "Unfolding Map" (in the collection Infra Noir), The Lustre of Time.

1 Comment

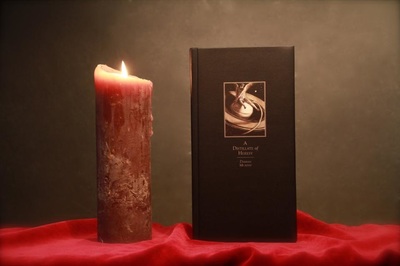

Jorge Luis Borges, in an extremely rich and suggestive essay entitled "Narrative Art and Magic" – compiled in the anthology Discusión (1932) – discusses the art of narrative was located close to the magic through the common procedures like analogies, unusual projections, the imaginative overcoming of the insoluble contradictions. A large arsenal employed for a simple goal: the transmutation of our usual reality and its strange causality in a new, complex reading. Damian Murphy, with his fiction, recovers this Borgean statements with new developments related to the games, the wandering, the initiation. In the novel The Salamander Angel (published in the collection Infra Noir), in the stories compilation A Distillate of Heresy and in his participation in the Fernando Pessoa homage, Dreams of Ourselves, Damian Murphy has set visionary relationships between magic and fiction.

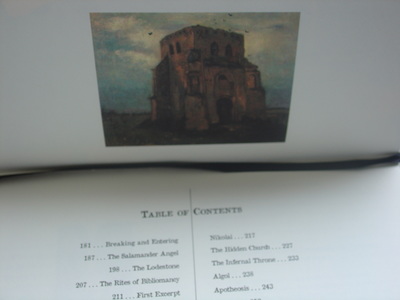

In your narratives, there is a very evocative fusion between displacement (wandering) and mapping (the conquest) of real and imaginary territories, the transiting sphere for your characters. The transitions between real and imaginary topography are subtle and complex, so that your narratives get a enigmatic complexion, related to the initiation rites. An extraordinary example of this call to wandering arises in the story "The Book of Alabaster", in which exploratory and initiation wandering happens within a virtual video-game universe. What would it be the origin of your perception of wandering? How do you set this paradoxical relationship between the free travel and the need for a map? I’ve long been fascinated with the very human tendency to spatialize experience. Dreams, visionary experiences, initiations, video games, and narrative itself all demonstrate different ways in which we do this. Different cultural approaches to the mysteries use spatial metaphors such as the cube (along with other geometrical forms), the temple, and the city, to illustrate states, ideas, and relationships which are too abstract to represent directly. It seems natural to me to draw parallels between the abstract maps found in Kabbalistic works and esoteric Islam, for example, and representations of geographical constructs found in video games designed for older systems. To this day, I’m compelled by maps of old video game areas (you can find these all over the internet) in the same way that I’m compelled by depictions of New Jerusalem or the geography of Tartarus. The initiatory experience relies on the dichotomy between mapped experience and free travel, as you’ve termed it. On the one hand, a ceremonial initiation conveys the initiate along a route defined by symbolic values. Geometrical formations might be traced along a temple floor, for instance, with confrontations at various localities which represent the elemental forces of nature, or the stations of the sun and moon, or the phases of an alchemical operation. On the other hand, the initiatory process almost always involves an entry into unfamiliar territory, a period of searching for something of worth which is hidden, forcing the candidate to adapt to an environment in which they have no previous experience. Often, in my writing, I’ll begin with a particular structure which is concealed from the reader. The story will then be constructed as a sort of initiation of one or more characters into the mystery which is at the heart of that structure. In this way, the reader is made to wander through an environment for which there exists a map, but that map has largely been withheld from them. I put a lot of emphasis on intuition and sensation - the numinous speaks far better through these aspects of experience than it does through the purely rational. Maps of the intangible are something which I’ve always been attracted to. History is littered with maps of visionary worlds - from Dante to Blake to Swedenborg, the list is endless. Thinking back over the stories which I’ve written, every one of them seems to feature the cartography of the invisible in some way. Some more subtly than others. There are numerous references to buildings intended for ritual (or turn to do so, due to the action of various forces) in your stories. Some of this temples are described as physical buildings, other mapped by the mind or perceived in the same way as reality impossibilities by the rational mind of the characters (but not by intuition). In this sense, I believe that “Permutations of the Citadel", as well as the novel The Salamander Angel (published in Infra Noir collection), are great examples of your operations building this fictional structures for strange and unusual rites. How do you set up, in your narratives, these unique buildings? Is there any model – conceptual or concrete – for your, so to speak, fictional design of temples? With “Permutations of the Citadel” I was absolutely obsessive in my construction of the hotel in which the story takes place. On the one hand, this involves floorplans, maps, particular routes by which the characters get from one place to another, and things of that nature. But, perhaps more importantly, the spaces in which the rites and mysteries take place have to seem absolutely real to me. I try to invoke the richness of the experience of occupying an environment, to imbue the various spaces in the stories with a genius loci which, hopefully, the reader can relate to in a more or less tangible way. Without this element, I’d feel that I was somehow cheating. I do use models in my construction of these locales - a mixture of physical locations and photographs. It’s very easy for me to create a space and occupy it mentally, exploring all of the fine details, the textures, the scents, variations in lighting. In a sense, these buildings are as real to me as any physical space. My intention is to never use the same method more than once when it comes to creating buildings and structures which act as nexuses for forces, mysteries, and rituals. In the case of The Salamander Angel, the ruined church is shown on several subtle levels, demonstrating the adaptability of a particular place to myth, to the cycles of heavenly bodies, to the progression of archetypal offices of influence (among other things). In “A Perilous Ordeal”, the abandoned manor house plays a very different role, while the same is true of the hotel in “Permutations of the Citadel” and the penthouse in “The Scourge and the Sanctuary”. Each instance demonstrates a different way in which a building or structure can exist beyond its physical dimensions. Something that seems general to me in your stories: the exquisite taste for paradox, the confrontation between concepts that do not usually belong to the same sphere of conceptual meaning or even the same semantic nearness. This appreciation begins with the very title of several of your stories. In "The Book of Alabaster," the object of the title initially is not what it seems (though in the end, this first impression proves misleading). The dangers and the ordeal of the "The Perilous Ordeal" protagonist are not exactly those that the reader knows in the first pages of the story, with the interruption of an initiation ritual by Nazi soldiers. In this sense, your novel The Salamander Angel is a work in which the construction of the paradox manifests itself in a more elaborate way, from the angelic approach in title (almost an oxymoron) to the multifaceted plot construction. What would it be the origin of your complex work with the paradox? I don’t know that I’ve ever set out to specifically invoke paradox, though I think I’m so disposed to them naturally that I probably introduce those elements into my writing without necessarily intending to. There are definitely places where I’m interested in the resolution of two opposing ideas or archetypes - reference is made in The Salamander Angel, for instance, to a place in which the celestial can’t be distinguished from the infernal. There are often opposing elements which must be resolved in one way or another by the characters as well. I do tend to create spaces and artifacts which can’t quite be pinned down to one thing or another. The “book” in “A Book of Alabaster” is one example. As an object, it exists in several different contexts, making it quite difficult to define, and yet there is a particular idea or concept which underlies all of its different facets, though I may not choose to reveal exactly what that is. An exciting aspect of your narratives is a kind of update of the "cautionary tales" powers from the functional use (even in the Fairy Tales tradition), turned to an ironic game based on the contrast between what the characters look and what they find. An object (or idea) seemingly simple proves much more complex, as the games that conjure objects/buildings and its realities in "Permutations of the Citadel” or “The Scourge and the Sanctuary”. In this sense, you provide to the reader a whole poetics of permutation as some processes started by seemingly trivial mechanisms – games, casual and accidental discoveries, unexpected encounters – that become, through exchanges and meaning conversions, much wider and more challenging. This is a narrative creation path that brings to mind the "theory of correspondences" between the planes of existence by Emmanuel Swedenborg. What is the basis of this subtle and rich narrative game? A certain amount of this is autobiographical. I’ve always tended to engage with my environment according to strategies which might be termed arcane, and to pursue things that aren’t generally valued, or even considered, by the majority of society. There’s a tendency for the characters in my stories to treat the world as if it was a game, or a mystery to be explored, or even a lover to be courted. Often a character will seek something without entirely knowing what it is that they’re after, or they’ll interact with their environment according to a set of rules which completely disregards the assumptions generally made about the order and structure of the culture in which they live. I’ll often lead a character into a place in which they’re not supposed to be. There’s an archetypal element to transgressing or crossing a boundary. There are whole areas of experience which can be invoked and explored in this way. Often, by way of a sort of sympathetic magic, the crossing of a physical boundary will result in the breach of a much more tenuous threshold. I find myself continually coming back to this dynamic and finding new ways to explore it. I’m fascinated by the things that people do in the places where they work. There’s something so compelling about the possibilities which lie just beyond the arbitrary boundaries of what we’re supposed to be doing in a particular context. Messing around on the job can be elevated to an art form, or, as in “Permutations of the Citadel”, an initiatory path. In The Salamander Angel, there’s a section in which the character Nikolai stands on the roof of the building in which he works and observes another night worker through binoculars. He might be accused of violating another person’s privacy, but he just can’t resist observing, with intense interest, the rites and incantations by which another person carries out their professional tasks. Within the stories themselves, I’ve enjoyed playing games with the reader, often deliberately making use of deception and misdirection in order to conceal narrative, thematic and structural elements which might alter the interpretation of the piece. There are almost always hidden layers that might be discerned by paying close attention to particular aspects of the story. Again, I try to avoid using the same trick more than once, so if a key to one story is found, it generally won’t fit with any of the others. There’s an element of play in this approach which is very necessary to my creative process. On the other hand, I try to avoid creating something which can be reduced to an elaborate crossword puzzle. The sense of place and mystery, the emergence of the structures and themes which are at the heart of the story, and the flow of the narrative all have to get equal attention. Your short (but remarkable) novel The Salamander Angel features a unique structure of complexity interactions: multiple characters, performing different ritualistic activities, composing a process that only reveals itself in all its amplitude at the end, loading the intricate plot with a kind of metaphysical suspense. Tell something about the construction of The Salamander Angel – problems and solutions, essential ideas to the plot and other questions about this brief jewel of fantastic fiction. When I began the story, I had little more than the opening paragraph and the first traces of the Breaking and Entering chapter. Having no idea what direction I wanted to take things in, I compiled a list of themes I wanted to include, and the scaffolding upon which the narrative is built immediately revealed itself. The ritualistic structure of The Salamander Angel is based on a particular process which I’m hesitant to reveal too much about. It’s an initiatory process, the core dynamic of which is quite audacious and foreign from the point of view of exoteric religion, yet traces of it can be found all throughout the history of western esotericism and literature. The implications of this process are at once catastrophic and harmonizing, it involves an extreme change in the point of view of the person undergoing it. My hope is that the reader will be enabled to approach the hidden mechanisms of the story, however obliquely, in an organic way by engaging with the characters, settings, and plot. In the story, the initiatory process takes place in the context of a building, a city, and ultimately the world rather than that of an individual (though each character is affected by it in their own way). Only one of the ceremonial officers seems to have the whole picture, the rest play their parts with only a partial understanding, at best, of what’s going on. This approach made the story a very enjoyable one to write. The other main theme of The Salamander Angel is transgression. Shortly before beginning the story, I was asked to speak at a public event in anticipation of a dance performance. The performance involved the Watchers of the Book(s) of Enoch, the Nephilim, the fallen angels and other related topics. I don’t remember exactly, but I don’t think I had more than a day or two to prepare. I quickly put together some thoughts on the theme of transgression on a grand scale, tying the stories of the fallen angels and the Nephilim to our very human tendency to transgress our natural boundaries, contexts, and limitations. Once I’d hit upon the main structure of the story, I found that these ideas fit perfectly. The other motifs – the Salamander Angel, the lodestone, the star Algol – each play their role in bringing about the transformation which may or may not take place within the story (there’s nothing to suggest that anything really happens other than the delusions of an unconnected group of eccentrics). I have a notebook in which the entire structure is plainly laid out, with explanations of all of the different elements - I wanted to have something to ensure that I didn’t forget what I’d done! Both in the novel The Salamander Angel as in the tales of the collection The Distillate of Heresy there are times when the usual structure of the plot becomes a little more abstract, poetic maybe. I think, for example, in the chapters "The Rites of Bibliomancy" and "First Excerpt” of The Salamander Angel, in which you have dropped the narrative causality in favor of a different approach to the fictional universe, more symbolic and guided in the aforementioned aspect of correspondence between different spheres – or if you prefer, the permutation way. In this sense, you want to work in other genres such as poetry, in the near future? Is there any of your future project already defined? I do have some ideas for pieces which embrace the poetic side of things more than the narrative. I expect that those elements will continue to erupt unexpectedly within the flow of narration from time to time as well. As for future projects, a new novella should be published soon. I’ll keep the details concealed for now, other than to say that it involves several mysteries found within Catholic liturgy. Aside than that, a new batch of stories is in the works. I have enough ideas to keep me going for some time, and inspiration has been increasingly kind to me as I get older, so I imagine there should be quite a bit more to come. Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). NOTE: The first three beautiful photos below were kindly provided by Jonas Ploeger, Zagava Press editor, with the covers from, respectively, A Distillate of Heresy, Infra Noir and Dreams of Ourselves. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed