|

There is a vertiginous moment that can occur daily or at least once in the life of each one, when we realize that everything around us is hollow, empty, and the life is nothing but a dream. This formulation is of course a cliché – true, but still a cliché. Maybe better reformulates it: our time is motionless. Like the arrow in one of the Zeno of Elea paradox of motion, we live in the perpetual stasis, the permanent immobility. Our gadgets, wars, refugees and everyday problems are only a foam briefly visible in the troubled sea. Thus we still live the time of the artistic avant-gardes. We are driven by the same contradictions, move us the same dramas, and our scandals are ignited by the same épater la bourgeoisie techniques. Perhaps this facts happens because the artists of the early twentieth century avant-garde discovered the secrets about a new narrative and theatrical genre: the universal tragedy – or perhaps, the universal comedy, because the two genres flow in parallel in this new form. The production of this unprecedented genre was unique: a drama, immense and uninterrupted, whose central theme is the annihilation of art.

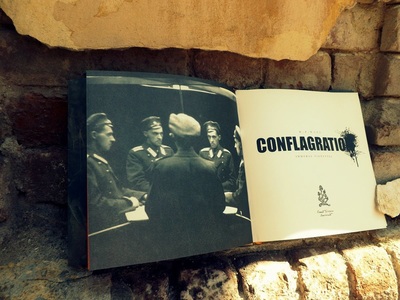

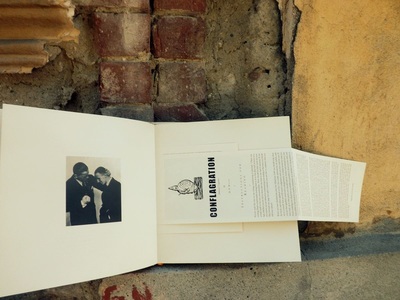

In this new kind of Gesamtkunstwerk unveiled by the avant-gardists, the audience on a global scale is invited to take part in an act in which the artists and their creations are crushed by numerous repressive forces, but still seek desperately to remain alive and conscious, despite all the violence and the temptations that include some souls sales off. The portraits, paintings, images, stories and tragedies vanguards of the twentieth century Avant Gard sucks the audience to the inside of a kind of play without stage, the maelstrom of other and apparently remote era; when we look at a painting like Umberto Boccioni's La città che sale (The City Rises), made in 1910, we have exactly that feeling, even if we ignore its creator or the central theme of the composition. The dynamic forms of men and horses in Boccioni image takes the viewer to a kind of abyss, another time, or better yet, another time possibility, in which the dramatic tension is permanent. So the righteous concerns of our time disappear before the uncertainties of the Bolshevik Revolution, the stylized barbarity of fascism, the terrible hyperinflation everyday, the civil, European and World wars. If we were to christen this genre of a unique work, premiered in the early twentieth century and still pulsating, we could use a synthetic and effective term: perhaps Conflagration, not coincidentally, this is the title of the D. P. Watt new work, published by Ex Occidente Press Bucharest through its new editorial persona, the Mount Abraxas series. The Watt's new book has a curious format: quadrangular, something that the editor had already employed in L'homme recent series but in a bigger format. The jacket has a continuous illustration (made by Misanthropic Art) as a poster, the image of a black sun at the center, mediating between a hand and eyes of immense and divine proportions in the polar sides, the two fields marked by the presence of human ornamental forms. Given this extraordinary jacket, the minimalist cover, as a default by the publisher, provides an effective counterpoint with his animal fur texture, its low relief and its orange color (the same for the page marker). As soon as we started reading the book (after extraordinary photograph that serves as frontispiece to the book, "Multiple self-portrait in mirrors" by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz) we are surprised by a brochure that shows us the "Instructions for Reading". Such instructions begin as follows: "Please read this text in one sitting, commencing at precisely 7.30pm one evening." This procedure, to guide the hypothetical reader in a recommended reading method according to the author, was used with similar purposes by Julio Cortázar in his experimental novel Rayuela (Hopscotch, in the most recent translation); as in the case of Cortázar, Watt invites us to disobey the rules established by himself, which incidentally we did just like Des Lewis in his excellent review of Conflagration (which can be read here). Soon after that first moment of estrangement, a Dramatis Personae as in a play appears. In this list, there are the names of the various avant-garde innovative theater creators in the twentieth century, from Alfred Jarry to Jean Genet, Bertolt Brecht to Eugene Ionesco, Vsevolod Meyerhold to Samuel Beckett. But the brief texts of the book does not follow the traditional structure of a play adapted to a book format. Brief and fluid narratives, this vignettes are marked by a date and a topographical title, time and an indication of place as "The streets of Trieste" or "Galerie Montaigne, Paris". These small narratives establish themselves on the balance between the abstract, the fantastic, the comic and the tragic. In this sense, the subtitle is revealing: "immoral vignettes", short scenes that could be staged as imaginative and critical (or ironic) commentaries about the contemporary (and historical) drama. Thus Beckett's universe resurfaces in the French countryside devastated by war. Ionesco's La cantatrice chauve materializes as false just in the time of its conception. The tragedy of Meyerhold unfolds clearly before the reader, to its inevitable end decreed by Stalinist orthodoxy. But these are only a few fragments, some of these voracious vignettes that seem to summarize all contemporary history beginning in Braunau am Inn, the April 20, 1899. In one of these vignettes, "Sprovieri Gallery, Rome", we have a vivid and dynamic description of the Italian Futurist theater. Suddenly, we are told that the images used as background to these presentations, representations of the mechanical vehicles speed and strength based on Neapolitan carnival, "were nothing but the force of speed and the energy of vehicles, the surging of movement and the violence of colour. They depicted only the passion of their own inception." Perhaps, this is the best way to describe this little masterpiece, a description that also fit to characterize the intents and unstable utopias, fragile, decadent and useless contraptions produced by the perpetually fascinating art of the avant garde in the twentieth century – a mist, a stream and a ghost, whose intensity dazzles and impresses all the witnesses by its own infinite driving force. The first three photos below were kindly provided by the publisher, Dan Ghetu.

23 Comments

The idea for the blog Bibliophage (and his sister, Bibliofagia) emerged during the now distant year of 2013. At the time, I studied the fiction of J. G. Ballard and worked on the translation of the book The Atrocity Exhibition for Portuguese. In the middle of this journey, I realized how weird, strange, fantastic and speculative fiction adopted, since its beginnings, the form of the book as a vehicle of expression for the sense of ambiguity and instability of the universe around us, the usual goal in this form of fiction. The development of these ideas led to the blog setup and the contact with fantastic fiction creators (authors, editors, artists) in activity. The project on Ballard is now closed, others have come since then, but the blog has remained as an extremely pleasurable activity, so useful for my studies as well. So why not share the pleasure it brings me reading and creating this mazy analysis for all these books?

But unfortunately, it is so hard to keep the blog alive: there are long gaps in posts flowing because every detail is systematically designed – the choice of the book, reading, material analysis, preparation of text, images shooting, etc. Thus, in order to blog maintenance and even the possibility of increasing the quantity and quality of published and future essays (I think even in video essays and audio interviews for the future) is that I ask the readers, who appreciate and understand both the needs of this work (unpaid, but with so much love, like building barricades according to Charles Fourier) to collaborate with my project through Patreon. Thank you in advance the attention and support. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed