|

In a recent past, a very large History of the World seemed a good idea: authors like HG Wells sought audacious narrative synthesis of the multilayered historical process. The efforts were elegant or eventually reductionist in the task of extracting a logic in the History, a process that has certain essential disorder, as said Jean-Paul Sartre. In fact, a possible criticism about universal stories, perhaps the most striking critic, is precisely the approach of historical fact, because the universal historian appreciates the wonder facts and great names in a seemingly continuous line of progress. However, there is another History, populated by people and events unjustly ignored, remote or marginalized. This historical otherness, that is often not even known, emerges in a unique form in the works of John Howard. The marvelous fiction of Howard addresses fantastical phenomena and philosophical questions in the edges of our history and cognitive universe – sometimes in totally imaginary regions, as is the case of his most significant topographical creation, Steaua de Munte, a exhilarating region of imaginary Romania that can be visited in his latest novel, The Lustre of Time. Even the supernatural in Howard creations is subtle one, almost imperceptible – the uncertainty is the poetic weapon of John Howard in his antithesis of universal history, an imaginary history, unique and terrible.

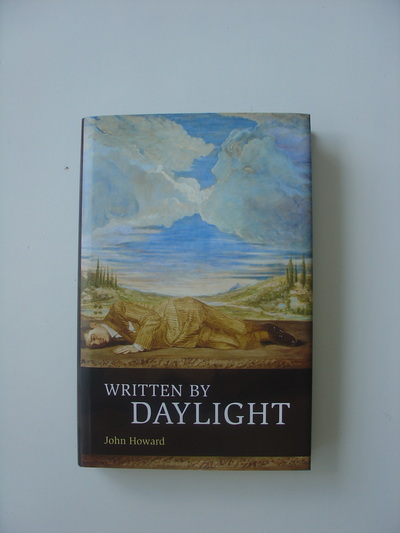

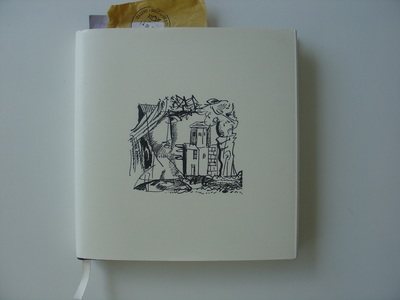

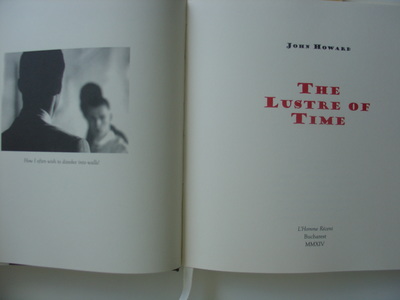

A very particular approach to urban topology, including the development of an entirely fictional town, Steaua de Munte, emerges in your works. This imaginary city is extraordinary, an entity that continuously develops itself over several short stories and novels, with its cafes, hotels, universities, hills, houses, buildings. It's an imaginary space equally or more extraordinary that William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County or Arkham by H. P. Lovecraft. So what would be the point of creating a fictional territory in such a distant place, covered in a peculiar picturesque mythology, Romania? What have been your sources and conceptual and imagery sources for the construction of Steaua de Munte? Modern Romanian history has interested me ever since I came across a contemporary account in John Gunther’s Inside Europe (1936, and subsequently much revised and reprinted). This was when I was still just a teenager and there seemed no reason for Communist rule behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ not to last for ever. I found Gunther’s portrait of the country as it had been nearly fifty years before my time to be utterly fascinating. Romanian politics were byzantine, Ruritanian, and murderous. And the country’s leaders – especially the flamboyant king, Carol II – seemed larger than life. John Gunther was an American newspaper reporter, a foreign correspondent in Europe for many years before and after World War II. He became one of those authors whose books I always look for. I have a shelf of them. I never forgot Gunther’s vivid and accurate summaries, and when Ceausescu and the other Communist leaders fell, it came as no great surprise to find their countries carrying on, in many ways, from where they had left off in the 1940s. There is so much in the histories of that part of Europe which seems almost operatic or something out of a television drama – if it had not been real, it could only be believed as fiction. But that is easy for an outsider such as me to say: these people were also responsible for ruining the lives of so many of their people. Fiction can examine the dark places – and should do. The opportunity to visit Romania came in 2009. The previous year Dan Ghetu’s Ex Occidente Press of Bucharest had published The Rite of Trebizond and Other Tales, a collection of stories mostly written in collaboration with Mark Valentine. Dan had read “The White Solander” – one of the tales of The Connoisseur that Mark and I had written together, and which had a Romanian background. Then Dan invited Mark and Jo Valentine and me to visit Romania. Dan and his wife were generous and painstaking hosts, driving us around much of the country in an exhilarating tour which nevertheless ended all too quickly and still left too many wonderful places unvisited. We crossed the mountains into Transylvania and stayed in the old cities of Sibiu and Sighisoara, and these were the main sources for my city of Steaua de Munte. But in most respects Steaua de Munte is a unique and special place, not dependent on anywhere else, and is what I, as sole proprietor, choose to make it – and remake it. Novels and series of stories set against a common background have always appealed to me, especially when the setting develops and changes, with various different aspects being revealed at various times, and yet which also leaves much to the reader’s imagination. Characters come and go (and families and relationships are vital) but the background scene, even when it changes, does provide a level of continuity against which new stories unfold and have consequences for the unwritten future. The protagonist of "The Fatal Vision" (the longest narrative of the book Cities and Thrones and Powers) and The Lustre of Time, Dr. Cristian Luca, embodies something of the archetypal figure: the modernist architect/urban planner acting as a demiurge, fighting world authoritarian and vulgar perceptions. This archetype has its own history, dense and multiform, and came even to the cinema through The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand's novel, adaptation directed by King Vidor in 1949. Luca was your personal view of this archetypal figure? What about the development of such character? Now I have to confess that I’ve never read The Fountainhead, nor seen the film – I must try and do so! Luca first appeared as something of a background character (although a pivotal one) in The Defeat of Grief, and I never planned on him appearing again. But he did! I never attempted to train as an architect – I wouldn’t have stood a chance – but I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in buildings and their creators (this also includes structures and engineering such as bridges and tunnels). As a teenager I found books on modern architecture, and was captivated by the architects’ visions. It was even more inspiring because they were being built: Brasilia, for example. Of course, there have been all sorts of problems and unintended consequences – but I have to respect, if not love, the soaring visions. I imagine Luca to have come alive to a vision of the future when he was a very young man. However, he had the intellectual ability to make something of himself, and also the social and political skills to navigate his way through minefields of academia and patronage. I do not intend Luca to be a ‘good’ man – in fact at times he has been a total bastard! But he does what he does in order to survive and remain true to his vision. This comes at a cost to himself and to those close to him. The highest success is only one step back from ruin and defeat. Hopefully Luca will return at some point. That man is a born survivor – he learns from experience! And he’s a genius. But as a human being he’s flawed, and certainly damaged. Some stories seem to generate characters who must work in the background, who influence and fix events, who wield power over others, but remain behind the scenes and in the shadows. They are the people who have to do things for other people because the other people can’t be seen to be involved. On the level of fiction I like these sorts of characters, and the ‘secret history’ of their worlds. They are not ‘nice’ or ‘good’ people – but they are as they are for a reason, just as people who take risks, hurt others, and cause damage have often themselves been hurt and damaged, somehow. Well-adjusted and contented people don’t make very interesting characters. In your narratives, the architecture (as a style, a form, a concept) becomes a exquisite element, not only related to the concrete spaces but also to the sensuous perception and physics of cities and their buildings, crossing the skin and bones in characters like Dr. Cristian Luca, mentioned in the previous question. Incidentally, there is in the novel The Lustre of Time a memorable passage, in which Luca declares his desire to dissolve himself, merging his atoms with the walls around. Where you located the origin of this personal and unique architectural approaching used in your stories? As I said, I came across modern architecture in books. But there was also the country I was growing up in. It was being built, or was still new. I’m too young to remember Harold Wilson’s 1963 speech in which – according to the internet – he said ‘In all our plans for the future, we are re-defining and we are re-stating our Socialism in terms of the scientific revolution. But that revolution cannot become a reality unless we are prepared to make far-reaching changes in economic and social attitudes which permeate our whole system of society. The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry.’ But I grew up in a country in which to some extent Wilson’s vision did get the chance to be worked out. The future was going to be brighter, cleaner, safer. Slums were being demolished and new housing built. In some places the ruins caused by World War II were finally being swept away – in London there was the Barbican scheme and Route XI. Sleek motorways crossed the country. Jet airliners like vast metal birds flew overhead, and I watched the Apollo missions on TV. Now we know that new solutions give rise to new problems, but to this child it seemed that only challenge and wonder was in store. I read comics and watched films and programmes on television which showed the marvellous buildings and world of the future, and I thought that one day I should see them and live in that world. Sometimes I feel that the bright future has been stolen, so perhaps I try to compensate for that loss in some of my stories. I consider specially outstanding your short-story “Twilight of the Airships”, a narrative based in a singular speculative concept whose climax, the “invisible battle” between the Soviet and Nazi airships, brought to my mind both the novel also populated with airships The War in the Air, by H. G. Wells and also certain Jorge Luis Borges tales as “El milagro secreto”. Why this approach to the airships as the plot defining form, in this particular case? However, your approach to the airship technology, far from conventional steampunk views, would be closer to scientific novels of H. G. Wells, Charles Hinton or J. H. Rosny? My interest in airships comes from childhood. Like most boys I was interested in mechanics and machines – the bigger the better. I had a Meccano set and lots of Lego bricks. I was never much interested in cars or trains (even steam trains) but I loved ships, aircraft, and rockets. I used to know how the various types of engine worked, how to recognise the different jet airliners and World War II planes, all that sort of thing. Sometimes our father used to bring home books for us that he’d bought, and on one occasion he gave me a book about airships – from balloons to the World War I Zeppelins to the great airships of the 1930s and the era that ended with the Hindenburg disaster. There were lots of pictures. (I wish I had that book now, but I must’ve given it away or lost it.) The thought of these majestic craft the size of ocean liners plying the skies in commerce and exploration still fascinates me. I’ve loved Wells’ work since first reading The Time Machine when I was ten or so. I only read The War in the Air fifteen years or so ago, and I expect it was in the back of my mind when I wrote “Twilight of the Airships”. There were also the real-life accounts by the crews of the German Zeppelin bombers and the British fighter pilots trying to shoot them down. My grandmother saw a Zeppelin shot down in flames over north London, and she had a postcard showing the smashed metal framework on the ground. Another confession – I don’t know Borges’ story at all. Another situation I should remedy. I am really not at all well-read! I realized a recurring interest (even obsessive, maybe) through your stories on maps and in the definition of borders. The greatest example of this interest is the novel “The Unfolding Map”, included in the Infra Noir collection, centered on the strange mystique of the borders redesign and reconfiguration, an operation that jump from paper to reality. Such interest would derive from European history? Or is a kind of experiment with the power of idea contrasted with the restrictions of material/political reality? Yes, I think my interest in boundaries and their changeability comes from being interested in European history, although my interest in European history probably only started getting serious after I’d discovered the concept that countries’ borders were not as stable as I might’ve thought. When I was thirteen or so I was bored during a school holiday. There wasn’t much to do where I grew up. I went to the town’s library, and then into the reference library, and for some reason took a historical atlas from the shelf. I remember taking it over to a table and sitting down – and then being plunged into a world of shifting frontiers, with empires rising and falling in tides of different colours washing across the pages as I turned them. I must’ve realised that this charted the passing of decades and centuries. Names that had persisted through the centuries would suddenly vanish and be replaced by new ones. It all illustrated to me from an early age that nothing lasts for ever. And of course I quickly found out that the European frontiers I saw in my parents’ atlas at home were extremely recent. If borders have changed in the past, they could do so in the future – and many in Europe did eventually undergo thorough change in the early 1990s. And it all happened surprisingly peacefully except for the terrible, unnecessary, break-up of Yugoslavia. I suppose the power of idea lies behind many such changes: nationalism and the desire of a certain group and/or its leaders to enforce views of itself based along ethnic, cultural, religious lines, for example. Changes of border are one of the outward signs of something else – and that is what can be fascinating to make fiction out of. Times of war and economic turmoil have often been accompanied (or followed) by great creativity, and ordinary people showing what is best in humanity. Of course, creativity can also be stifled from above during such times, and people show the worst aspects of human nature. But I think treating these sorts of themes in fiction, and including real events and people from history can allow new insights to be born from the new stories. Or we can be reminded about things we ought not to forget. Behind border changes, behind the reality of changing the names of cities and streets, behind banning a book or smashing an artefact, there is also the reality of human cost, human loss, human pain. And yet there can still be humour, the bearing and sharing of burdens, the creativity. It seems to me that most people will always try to defy and overcome restrictions, however that might be in their different situations. Fiction can show that. The uncanny or weird effect in your narratives is quite subtle, with a hard philosophical investment. The strangeness in your stories is a gradual aspect, unveiled momentarily and covered again – an effect achieved by the clever use of continuity fragmentation and changes of views in the plot. Tell me about the process of creating this conceptual strangeness/uncanny/weird which I believe should not be enjoyed by certain fans of hardcore supernatural horror. I don’t think I’m aware of any conscious process – it just happens (or fails to happen)! I write very much by instinct, and quite often begin a story with no real idea of how it will end. I find that the process of writing a story tends to generate what then gets included, more so than any notes and outlines I might prepare first. What I do know is that I like subtlety rather than ‘blood and guts’ – although there is a place for that in supernatural horror fiction. Whether it’s always accurate or not, I prefer to think in terms of the ‘numinous’ rather than the ‘supernatural’ – although when it comes down to it I don’t really mind what labels get added! One of the essential aspects of your narratives – even before any editorial treatment – is the elaborated imagery, sometimes evolving for a visionary formulation. It would be extraordinary to see some of your stories, such as “Out to Sea” and “The Waltz of Masks”, in movies and on television. What is your connection with the aesthetics and cinematic thought? Do you have any future projects for cinema or television? I do tend to think in pictures, and I think that’s one of the reasons I often begin a story with uncertainty as to how it will end. Or sometimes it’s the end or climax of the story (not always the same thing!) that occurs to me first, and it occurs in visual terms. Then I make a note of it and then try to work out a story which can include it. “The Waltz of Masks” was inspired in part by the great set-piece ballroom and party scenes in one of my favourite films, Oberst Redl (directed by István Szabó). These are gorgeous and magnificent, feasts for the eyes (as well as the mind – as the entire film is). I don’t seem to watch as many films as I once did, but the ones I really like I’ve seen so many times and still watch again and again that I feel I know them well – although they can still throw up surprises, which I like! No, I don’t have any plans for cinema or television projects, and they’re not things I’ve ever considered doing myself. But I would certainly be open to anyone who wishes to adapt or collaborate… Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). Below, some works by John Howard: Written By Daylight, Secret Europe, Cities and Thrones and Powers, "Unfolding Map" (in the collection Infra Noir), The Lustre of Time.

1 Comment

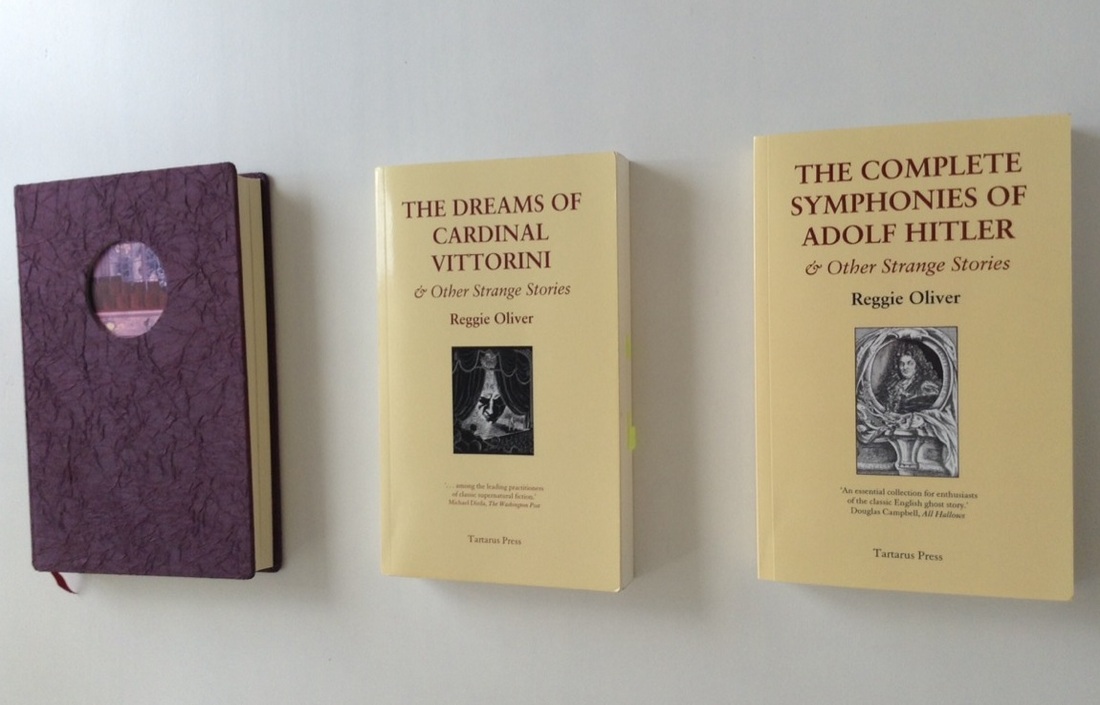

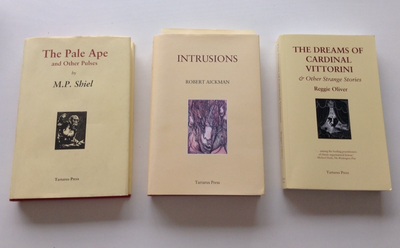

mong the narrative tools universe, the dialogue stands as one of the most complex and fertile: this interaction between the characters through communication devices (immediate or not) allows the oscillation between the said and the unsaid, expressed and hidden, true and false, intentionality and involuntary. At the same time, the dialogue connects the flow of human existence in narrative terms mimicking the numerous discussions that impart (or not) our existence with meaning. The drama, no doubt, places this tool at its center, but it arises in other conceptions of plot; for example, the philosophical dialogue since Plato, who knew how to put the dialogue in the service of philosophical exposition and irony, the element that dialogue facilitates and enhances. In this sense, the playwright, biographer, short story writer and novelist Reggie Oliver captures both the theatrical tradition and the use of dialogue as a tool to improve the irony impact, and it is one of the most skilled contemporary writers using the powerful tool of dialogue in his plots. Accomplished atmosphere builder both in short stories (in collections like The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini or The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler, both by Tartarus Press) and romances (The Dracula Papers, Book I: The Scholar’s Tale by Chômu Press and Virtue in Danger by Ex Occidente and Zagava Press) endow his ghostly plots of fierce urgency and complexity – unfortunately rare in contemporary literature.

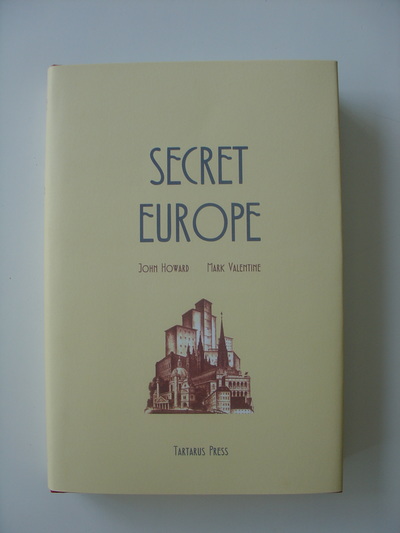

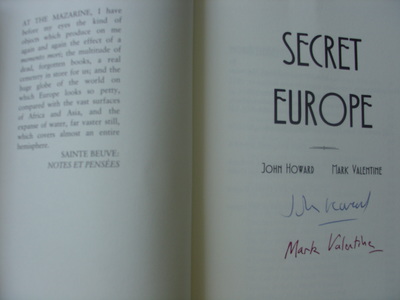

The theatrical universe arises in many of your stories, some like elements essential to the atmosphere and ambience. However, there are plots such as, for example, "The Black Cathedral" or "Evil Eye" which, although far of that theatre atmosphere had some theatrical aspects and complex scenes. It seems to me that in this sense, the dialogues appear as the key element in such a process, the dialogue as the way to the revelation small or big details. You could talk about how is the development of dialogues in your plots. I began my writing career as a playwright, although I was writing prose fiction as well, but my first professionally published works were plays. I have continued to write plays and have had some success also with translations or adaptations of French plays. What I enjoy about the use of dialogue is that it can show or suggest without stating. This sets up a relationship with the reader who can pick up on what is happening without being told. To give a simple example. I could say simply X was very angry but pretended not to be. Or I could suggest it by dialogue by having Y saying: “You’re not angry, are you?” And X saying: “No, I’m not angry! Of course not! I’m not angry at all.” That way, you not only make the scene more alive, you manage to suggest all sorts of things without spelling it out, like X’s irritability, his hypocrisy, his possible self-deception etc. etc. It is a primary principle with me that readers should be given the space to have their own views of events, to work things out for themselves. In “Evil Eye” which, as you perceptively point out has theatrical reverberations, I was concerned with ideas about spectators and participants. A spectator merely by spectating can alter the character of what happens. Perhaps one could go so far as to say that there are no such things as spectators, only active or passive participants. Also, the theatre universe appear as a backdrop for some of your stories seems so detailed to the reader that suggest a profound experience with such a universe, a deep knowledge about the daily out of scenes dramas and questions. It is a reflection of your personal and professional experiences, or a matter of search/retrieval literary backstage narratives and plots? In any case, what about the maturation process and research in plots like “The Copper Wig” or “The Skins”? My mother was an actress and I grew up around theatres. I have always loved everything about the theatre, particularly this interplay between illusion of reality. Stories are derived partly from my own experience, partly from stories I have picked up from my mother or old actors and actresses I have worked with. Performers, when not acting, are great story tellers. For example “The Copper Wig” which is set in the 1890s, derives from a number of sources. I talked with various actors who had been in the profession before this first world war and they gave me odd little details which bring the story to life, like the theatrical Sunday trains which were often met by theatrical landladies touting for custom. The detail about lying in bed in the morning and listening to the clatter of clogs on cobble stones as the mill workers went to the factory I got from my mother. On the other hand the copper wig itself I got from my own experience. I once shared a dressing room with a bald old actor who had a variety of wigs which he had neatly arranged on wig blocks, looking, from the back, like a row of neatly severed heads. The one that particularly fascinated me was a bright copper colour which gleamed under the strong dressing room lights. “The Skins” derives partly from playing the “skins” part in pantomime of King Rat in Dick Whittington, partly from the memory of a husband and wife variety act I once worked with. I am interested in the “quiet desperation” of most lives lived in the theatre: not the stars who achieve fame and success but the moderately talented people who just keep going. I am interested in how we bear our own mediocrity. One of your stories that impressed me most was "The Boy in Green Velvet", because there is in it a universe of suggestions which we have only a vague perception, a human vileness so terrible in which the supernatural element appears only as a catalyst. The same impression astonishing, indeed, I had to read another of your flawless narratives towards construction aspects, "The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini". Both plots, moreover, using unreal objects or almost unreal (paper theatre toy, memories of a lost book) in the construction of the narrative. In your opinion, this suggestive effects would rises from the objects in the scenery? As a note, when I visited the Benjamin Pollock's Toy Shop in Covent Garden, his short story "The Boy in Green Velvet" appeared, materialised before my eyes. The toy theatre – a very English phenomenon, though it has been picked up on the continent – has always fascinated me. I think it was because of the very peculiar and strange world it evoked of 19th century theatre before the advent of “realism”. In “The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini” I used various manuscripts and documents to give us a glimpse into worlds very different from ours, strange and terrible ones, which throw back a strangely distorted image of our reality. Human beings can be very responsible for the world in which they live: the worlds of Alfred Vilier and Cardinal Vittorini in “The Boy in Green Velvet” and “The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini” respectively are fearsome and not like our own, I hope, but they have the power to infect our world, and this is interesting to me. A persistent theme in my stories, very much taken from life, is the way people with powerful egos can, if one is not careful, take over another person’s life. What difference do you feel in terms of building between shorter and longer plots, like the tales of the collections by Tartarus Press and the novels like Virtue in Danger (whose subtitle is quite suggestive, The Metaphysical Romance)? Have you any preference among these formats? My tendency has been towards the form of the longer short story or the novella in which there are several “acts” but where a single theme or image can be held to without tiring out the reader. In my two novels The Dracula Papers and Virtue in Danger I have created a world, a microcosm, in which the events occur. In the case of Virtue in Danger I have created quite a narrow and circumscribed world – the headquarters in Switzerland of a religious “cult”, but to populate it I have created a large cast of characters and a wide range of action from tragic to farcical. The short story is the most powerful medium for evoking a mood, an atmosphere, a character. In the longer form of the novel that mood or atmosphere becomes dissipated or simply too oppressive for the reader. Chekhov, Maupassant and Walter de la Mare, to name three of the greatest short story writers of all time, are all masters of mood and atmosphere. You seem comfortable in working with phantasmagorical elements associated with contemporary gadgets, from TVs to video-game consoles, which is curious because many imaginative contemporary authors (as Mark Valentine or D. P. Watt, for example) seem to prefer older gadgets or objects of another nature. How did this your resourcefulness with these new phantasmagoria objects? I believe in a metaphysical realm. I prefer the word metaphysical to supernatural because I do not see it as somehow “super”, that is above nature, but rather working “meta” alongside the physical world. In my view it is a living reality, and therefore just as likely to emerge from a computer as from an ancient grimoire. Modern technology moreover is constantly trespassing on the ancient world of magic. A few hundred years ago something like a television would have been seen as a “magical” and deeply sinister object. Equally Dr Dee’s “scrying stone” might be looked on by us as a kind of primitive television. All technology, moreover, is a two edged sword. The surveillance equipment, for example, in “Evil Eye” can be used for good or, in the case of the story, utterly malign purposes and can therefore be imbued with the evil of its abusers. In your most recent novel, Virtue in Danger, there is a quasi-religious movement and a rich row of characters, both seem emerging from a film by Luis Buñuel. Some critics, as D. F. Lewis, speech in some Hitchcockian ambience and complexities in this novel as well. Could you talk about the building of this characters in particular? Is there any cinematographic influences? Interesting you should say that because I have also written Virtue in Danger as a film script. It’s promising but far too long and I am consulting with people who are more expert in film than I about it. I naturally see story cinematically - in other word in “scenes” with close-ups, wide shots, montages, “dissolves” and the like. When writing for me really works it is often like simply describing and transcribing the dialogue from a film showing in my head. Many of the characters in this book are very loosely derived from actual historical figures most of whom I never met. But I got an impression of them from their writings and anecdotes about them told by people who met them. The key for me with characters is always speech. If I can hear them talking, then I know they have come alive. With the central character of Bayard, for example, it was that weird mixture of public school heartiness and quasi-religious pietism in his speech which unlocked his character and its inherent contradictions. People often inadvertently reveal most about themselves when they are being insincere. One of the elements that makes your stories remarkably is undoubtedly your work in graphic illustrations that dialogue with the fictional universe of the text. In this sense, moreover, is not just to “enlighten” the text, but use the visual element as a meaning boost to the expressed in the plot. In this sense, how is your illustration construction work? You write the story and then leans over to synthesis it in images or vice versa? The image is always made afterwards when the story is complete. The business of making illustrations for the story collection is done when all the stories are written and a table of contents drawn up. I enjoy doing the drawings very much because I can listen to music while working on them. I cannot possibly listen to music while writing. I never make the drawings simple illustrations of an event in the story; rather they are an impressionistic rendering of one or more of the story’s images. They therefore provide a reflection on, or an insight into the story. Here is my idea of the story, I am saying. It may give you a further insight, but it is not definitive; it is no more valid than yours, the reader’s. The chief means for understanding the story should be the reader’s imagination; my drawings are simply a little additional spy hole onto it. I have come to value them increasingly as part of the experience over the years, and I am aware that they have helped to distinguish me from others working in the genre! The irony is an effect that seems to me to arise from varied and complex ways in your short stories and novels. The way it appears, for example, in “The Golden Basilica”, “Lapland Nights” or “The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler” is almost like the philosophical work towards the destruction of apparent meanings towards new possibilities – something close to the idea of irony in Kierkegaard for example, that stated about the “life worthy of man” starting by the irony. The effect of irony in his plots possess an imaginative or philosophical source? Jules Renard in his journal wrote: “Irony does not dry up the grass. It just burns off the weeds.” I agree. Irony is the conscious expression of a realisation that there exists a gap between human illusion and reality. No truly serious writer can lack a sense of irony, but that should not preclude compassion. We should be aware of the “vanity of human wishes” and the emptiness of most human achievement, but this should not prevent us from feeling sad about it. “Life is a comedy to those who think and a tragedy to those who feel,” wrote Horace Walpole. To a writer it should be both tragedy and comedy, and often simultaneously. To put it another way, both detachment and empathy are necessary. My aunt, the novelist and poet Stella Gibbons, would often discuss these ideas with me. She derived this from her reading of the writer she most admired, Marcel Proust. Is there any interest in you towards the creation of imaginative/strange/weird fiction for theatre or film, for example? How would you believe his plots will work in audio-visual or theatrical fields? There is. I began life after all as a playwright. It is an area which I hope to explore more fully in the coming years. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. Mark Valentine is a remarkable author who works the contemporary tradition of a kind fiction whose name is legion – fantastic, imaginative, visionary, weird, strange, uncanny, supernatural and so on. He is also had biographical works about important contemporary writers of imaginative fiction (Arthur Machen and Sarban), a scholar of the fantastic genre at the magazine Wormwood and blog Wormwoodiana. Valentine built a fictional universe full of details, filigree and subtle shifts of everyday reality in books like Secret Europe (with John Howard), At Dusk (both by Ex Occidente Press) and Seventeen Stories (Swan River Press). It is not absurd to say that this elegant fiction would be dredged by the attraction power of poetry, and it is possible to see in one of his latest books, Star Kites (Tartarus Press).

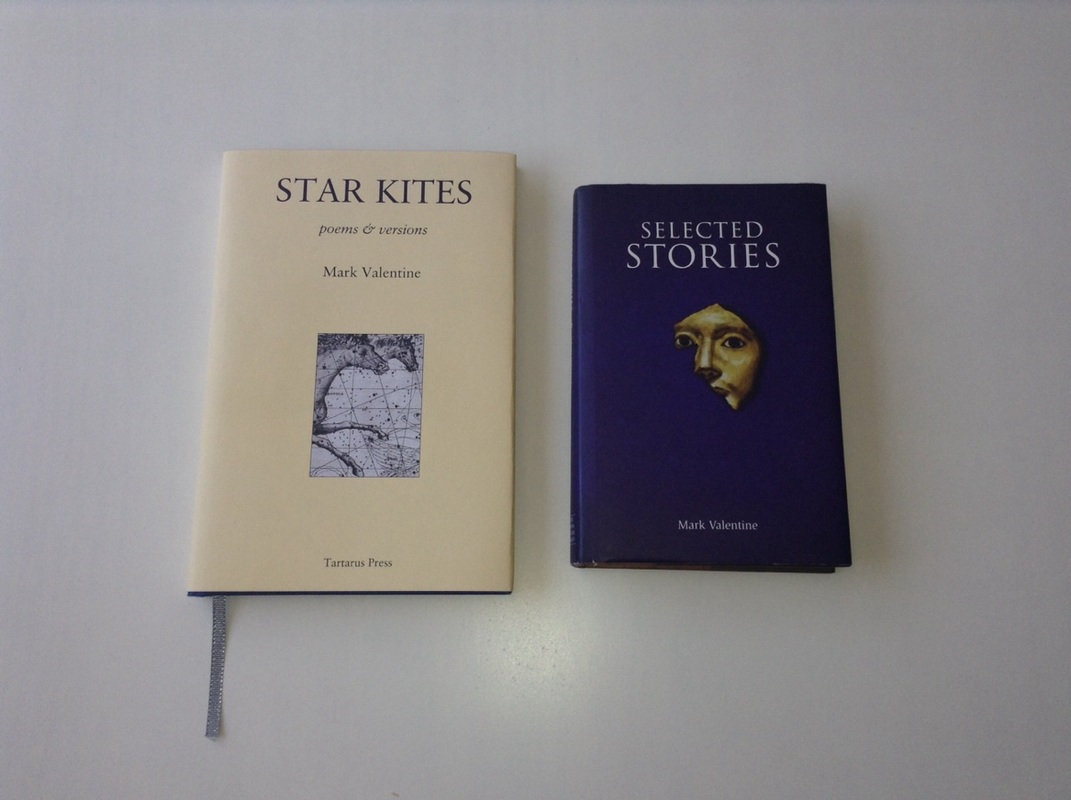

One of your latest books is a volume of poetry, Star Kites. The poems presented in the book have a tendency to disintegration of elements on the perception of reality – objects, shapes, even raw materials like marble – seemingly simple but impenetrable (as in the poem with the so suggestive title, "Marble"). This effect was obtained without tricks like objets trouvé or another surrealist intervention. Moreover, this work with the object seems inscrutable feed your creation as a writer. Could you talk a little about your relationship with this usual object, with the same matter, which suddenly turns into a fantastic element, unstable and unpredictable. In my childhood, toy marbles were usually not made of marble, but of glass: real marbles were very highly regarded. Nevertheless, though of glass, they were still shining talismans. In the poem “Marbles”, I try to evoke what these “little beautiful lost planets” meant to me as a first sign of wonder. The swirls in the marbles were mysterious: their colours were a delight. The game involved, of course, rolling these precious spheres along the gutter, to try to strike against your rival’s marble, which meant you won it from them. So there was always an edge of peril and a chance of plunder: you might at any moment lose your own favourite or gain another. And there were other risks: your marble might, as it rolled, disappear down a drain forever. So to this boy’s mind, beauty and wonder were also fraught with fragility and loss. But that did not stop the game, any more than we, mirrors of wonder, can avoid the dust. There is a noted quote by Arthur Machen to the effect that we are made for wonder, for the contemplation of wonder, and it is only taken from us by our own frantic folly. He also noted that “All the wonders lie within a stone’s throw of King’s Cross”, a busy railway station. He did not mean, of course, there was anything special about this area of London: he meant that “all the wonders” may be found anywhere. And so I have found: when we take the chance to stop and look, then a stone, a leaf, a shadow, rust, moss, rainwater, can seem to us strange and beautiful. There are also moments, rare enough, where what we see seems to tremble on the edge of becoming something else: as Pessoa said, “everything is something else besides”. I try in my writing to suggest these things, as best as I can. In the second part of Star Kites there is a work of recovery, and reconstruction, of the poetry traditions (and the poets as well, in the verge of the narrative representing some kind of authentic seer or metaphysical witness in the World) represented by a sort of opaque language (Esperanto to Portuguese, represented by two great authors of modernity in Portuguese, Fernando Pessoa and Florbela Espanca) and style (Ernst Stadler, known as German Expressionism prototype recovered in its most symbolic and mystical) to the point of view of usual reader. Not exactly a translation, but a task of essential and singular visions recovery of these authors, expressed in the poems. Thus, this part of Star Kites brought to mind the stories about poets of your At Dusk. Was there really a relationship, a joint project between the two books? As observation or curiosity, I add that "The Ka of Astarakahn" was one of the best stories I've read in 2012. Yes, both At Dusk and the versions in Star Kites come from the same inspiration, the modernist poetry of the first half of the 20th century. I think that even the most canonical figures in this field can be too little-known amongst English-speaking readers. Those who are further out, on the horizons, are even less known, and yet there is so much to discover here, so much subtle, strange, visionary work. I wrote the versions in Star Kites first, as a way of getting to know the work better: the act of translation is also an act of homage and respect. I am sure that other, better, versions than mine could be made, but quite a few of these poems had never been translated at all, so at least I have made a start. Then, after these, At Dusk is an experiment in a new form. Most of the passages mingle my own phrases, attempted epitomies of the poets, with allusive (rather than direct) quotations. This was an attempt to try something different in the way of "translation" in the broadest sense - the next step further on from the idea of "versions". As with the selections in Star Kites, I chose poets both from the acknowledged canon of modernist poetry and from further out: lesser known poets and lesser known languages. Many of those I chose were cosmopolitan in outlook, using several languages, and choosing (or being forced into) exile: their very lives and work question the validity of nationalism. The modernist poet has no nation but the library, and no language except the images of the spirit, glimpsed. Another front of your fictional creations was, apparently, the empire's twilight: there is in many of his narratives attempting to retrieve a particular universe, these crepuscular atmosphere of empires in the early twentieth century, notably the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Tales like "The Dawn at Tzern", for example, capture something of the atmosphere of this fascinating historical moment on the edge of the World War catastrophe, orderly and traditional, but carrying unthinkable chaos in its structure. Tell me a bit about your job in recreating this historic moment, if would be some consult to historians texts, for example (or, if it is the case, movies, photos, etc.) essential in recreating that subtle feeling. There has been a tendency for history to be viewed from the centre, the capital. In “The Dawn at Tzern”, I asked myself how the news of the death of the very long-lived Emperor of Austria-Hungary would be received further out, on the edges of the Empire, in some remote village. I wondered both how the news would reach the village and what effect it would have. The story tries to explore this through several characters: the diligent postmaster, the radical cobbler, an exiled priest (for what other sort would be sent here?), and soldiers in retreat from the war. The visionary youth Mishael is a shadow thrown by one of the three Jewish youths condemned by Nebuchanezzar to the fiery furnace, who came out unscathed, due to angelic protection. He is still safeguarded, but he remembers his protector in a changed way, as a form from Jewish folklore, a strange great bird. The story tries to convey the different ways open to the dying empire; duty, faith, magic, revolution, retreat. The details are mostly imagined, but it has a little of the influence of Bruno Schulz's story "Spring" and Herman Hesse's novel "Demian". Of course, I do not say it aspires to these. In the previous questions I mentioned historical issues about universes and unique traditions rebuild or evocation, in fact, this is an important facet in your work as a whole, I think. In this sense, your work as a biographer (of authors such as Arthur Machen and Sarban) and as an editor and critic (in the journal Wormwood) would be directly related, would impact their sphere of fictional production or the reverse would be correct? Yes, I was once asked why I devoted time to forgotten authors when I might be writing fiction instead. The answer is that the two fields often work well together. For example, my story “The 1909 Proserpine Prize” imagines a strange episode in the judging of an Edwardian literary prize for dark fiction, partly inspired by my reading of such work. Also, I like to write pieces where the line between story and essay is not always clear. “White Pages” seems to be about a series of authentic Edwardian novelty books issued by a certain publisher, which were mostly ways of making books of blank pages seem more interesting and exciting. Almost everything in the piece is factual, drawing on my research here, but there is a slight turn towards the end which changes the essay into a story. I may also add that when I am writing about a lost or forgotten author, and dwelling upon their life and work, it often seems that some unseen presence or semblance of the author is about, as if they are keen to see their story is told. There is a type of character that you worked a few times: the detective in themes about the occult and the supernatural (for example, Ralph Tyler and the Connoisseur, in collaboration with John Howard). However, your narratives constructed around these character types retain the visions and obsessions that could be found in many of his plots and poems. Apart from the obvious references and tributes, which would be more around these occult detectives peculiar that you invented? Are the narratives based in some historical events, facts and people? The Ralph Tyler stories, which were mostly written in the Nineteen Eighties, are usually set in my home county of Northamptonshire, an unregarded area, essentially a crossing place. They sometimes draw on authentic local history and folklore, but more often the inspiration is the landscape. It has rightly been noticed that this country reveals its mysteries more to the dweller than the visitor: for on the surface it seems pleasant but unremarkable. When I grew up there I would often walk or cycle along lonely lanes to remote villages, and I hope some of my sense of this “lost domain” might have found its way into the stories. The Connoisseur stories, by contrast, often have beneath them the idea that certain properties may be found in art or craft that will offer us a hint of the numinous or magical, and that these may be found at times in everyday objects too. The effect of sunlight or shadow can transform how we see a piece, and I sometimes wonder if there are other transformations possible too, either in how we see, or in how something is. A famous partnership in crime fiction (and film as well) was that of french authors Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, creators of plots that gave rise to such films as Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958) and Henri-Georges Clouzot Les diaboliques (1955). The partnership between of the two authors worked as follows: Boileau came with the plots and Narcejac, atmosphere and characterization. In the case of The Connoisseur, I believe that the way to creating was another, was not? How did working in partnership with John Howard? The first volume of Connoisseur stories, In Violet Veils, was written alone. In the second volume, Masques & Citadels, there were two of the stories, one about interwar Romania and the other about the first crossing of Spitsbergen (Svalbard), where I had made a good start but did not see how to go on. John was able to rescue the stories. This worked so well that we shared all subsequent stories in the series, so that John is rightly now a co-creator of the character. We also wrote a shared volume, Secret Europe, set among the cities and remoter places of interwar Europe: however, in this case, the stories were written individually and are simply published together. John has also, of course, published several volumes of his own work, most recently Written in Daylight (The Swan River Press, Dublin), which ought to be read by anyone who enjoys subtle, finely-shaded supernatural fiction. Are you working on some new narrative or project (there are many characters and plots like The Connoisseur or the poets life of At Dusk that would be fantastic in the Movies) at the moment? Talk about some of your future plans. I don’t know very much about film. I have never owned a television and rarely go to the cinema. Among current projects, a few turns of chance have recently led me back to some sound recordings I did in the early Nineteen Eighties. I was much impressed then by the do-it-yourself spirit of new wave: like many others, I published a zine and wrote for others, and issued my own tapes and contributed to others. That restless sense of just getting on and making things, even if you weren’t trained or proficient, has probably been a great influence. Recently, an experimental musician has been working on pieces based on crude reed organ tunes I recorded then: and a field recording I made (with others) of the sea and a lighthouse foghorn in West Cornwall has been broadcast regularly on an online radio station. I’m also started to look at old, time-stained book covers as a form of abstract art: how the chance markings can seem to have mysterious forms. With my wife Jo, under our Valentine & Valentine imprint, we’re also issuing handmade books of pieces that wouldn’t find larger publication: rare lost literature, translations, obscure essays and prose sketches. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. Ray Russell runs the Tartarus Press with Rosalie Parker, but had some fiction works already published at other publishing houses (Ghosts, Russell collection of stories, for example was published by Swan River Press). In the rich Tartarus Press catalogue, it is possible to find titles by old masters like Arthur Machen, H. G. Wells and the Robert Aickman complete "strange stories" works. But contemporary writers is not overlooked at the Tartarus catalogue, with works by Reggie Oliver, Mark Valentine and Anne-Sylvie Salzman.

Could you tell something of the History of your publish house? Perhaps the first steps, initial ideas, choice of first authors, difficulties at first moments and the aims and strategies in the very first days. Tartarus Press was initially set up by me, Ray Russell, to publish a few booklets for friends and fellow enthusiasts of the work of Arthur Machen, Ernest Dowson and John Gawsworth. The first mistake I made was to use the profit from my first booklet to pay for the second, which was then given as a gift to those initial customers. For the third booklet I had to start all over again financially :-) The first Tartarus Press hardback, Chapters Five and Six of The Secret Glory, came about because I had been transcribing the manuscript of the previously unpublished parts of Arthur Machen’s novel, and various friends asked if they could have a copy when I had finished. Publishing it as a proper hardback book was the most sensible way of making it available. The main problem I encountered in the early days was unscrupulous printers who told me they could print a book for me, but obviously couldn’t! Finally I found The New Venture Press, who had not printed a book either, but were honest about it. We worked out how it should be done together, which was very instructive. Then we had to find binders… In those early days it was a hobby, without any idea that I might try and make a living out of publishing, as I do now. Some publishers have a unifying vision or even a principle, a theoretical formulation that serves as some kind of guideline. There would be something similar in the case of Tartarus Press? It would be possible to define your editorial house with an idea, a word, a speculative notion? I started Tartarus with the idea of simply publishing and sharing obscure writing that I really enjoyed. My partner, Rosalie Parker, joined Tartarus about fifteen years ago with a determination to do exactly the same thing. The publishing policy of Tartarus is still guided by our personal literary tastes. In my vision, I realize that there are two paths preferred by Tartarus Press: one, digging in the early, forgotten and/or traditional imaginative works by authors like Arthur Machen, Thomas Owen, H. G. Wells, Robert Aickman, etc. The other one, more focused in contemporary authors like Reggie Oliver, Mark Valentine, Nike Sulway among many others. There are, in this dual pathway, some kind of balance between two sides, even in the editorial choices (authors and titles)? We see the historic and the contemporary writers as being complimentary. A love of the work of Arthur Machen led naturally to us publishing Walter de la Mare and Oliver Onions. L.P. Hartley took the supernatural fiction genre further forward into the twentieth century, and Robert Aickman was their natural modern successor in the second half of the century. And by publishing contemporary, twenty-first century authors like Simon Strantzas and Mark Samuels, there has been a line that can be traced back down through all those writers I have already mentioned. Obviously, Angela Slatter and Nike Sulway are writing in a slightly different tradition, and Reggie Oliver with a different background again. The Tartarus Press editions, even in the paperback form, are beautiful in every sense. The short-run editions is a huge indicate of this precious work. But there are a solid investment, as well, in e-book edition, with the careful attention to nearly all formats available. This editorial vision at Tartarus could be a way between physical and digital war format in the book market, perhaps? Are there plans to expand the digital production at Tartarus Press? At heart we are book lovers, and nothing can replace the enjoyment of reading great fiction in a well-made book. As soon as I started to understand book production, I wanted to produce beautiful editions that I would want to keep and read myself. It was tempting to try and print books letter-press, and have more bound by hand, but we didn’t want to make them unaffordable. I hope we have a good compromise. But realising that our limited edition hardbacks are still perceived as expensive by some readers, paperbacks have been introduced for reprints. We still try and make them as elegant and nicely-produced as possible. Ebooks are less enjoyable to produce. We know, though, that for some people they are very convenient. It has very hard to sacrifice so much design work to create ebooks, but we make them as well as we can. Are there a best/favorite edition or collections for the Tartarus editors? As with your own children, it would be unfair to choose some over others! A recent edition, The Life of Arthur Machen by John Gawsworth, had a interesting extra: a DVD with a BBC film about the book theme. This is a familiar format for the Film Art collectors (usual at some DVD/bluray labels like the American Criterion Collection) and it's great to find in a book with the already mentioned Book as Art Object vocation. But are there another plans for editions with films and audiovisual material as bonus/part of the edition? There are no immediate plans for us to become multi-media publishers. The John Gawsworth DVD was a fortuitous opportunity that we couldn’t afford to miss. We will always be primarily an old-fashioned print publisher. In the same way of the last question: what about the Tartarus Press future plans? More translations or the archeological task of Master Works restoration? We are superstitious about discussing future plans, because announcing projects too early often means there is some reason why they are then delayed… We do have new books by some great contemporary authors on the horizon – some known and some unknown… This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed