|

The idea for the blog Bibliophage (and his sister, Bibliofagia) emerged during the now distant year of 2013. At the time, I studied the fiction of J. G. Ballard and worked on the translation of the book The Atrocity Exhibition for Portuguese. In the middle of this journey, I realized how weird, strange, fantastic and speculative fiction adopted, since its beginnings, the form of the book as a vehicle of expression for the sense of ambiguity and instability of the universe around us, the usual goal in this form of fiction. The development of these ideas led to the blog setup and the contact with fantastic fiction creators (authors, editors, artists) in activity. The project on Ballard is now closed, others have come since then, but the blog has remained as an extremely pleasurable activity, so useful for my studies as well. So why not share the pleasure it brings me reading and creating this mazy analysis for all these books?

But unfortunately, it is so hard to keep the blog alive: there are long gaps in posts flowing because every detail is systematically designed – the choice of the book, reading, material analysis, preparation of text, images shooting, etc. Thus, in order to blog maintenance and even the possibility of increasing the quantity and quality of published and future essays (I think even in video essays and audio interviews for the future) is that I ask the readers, who appreciate and understand both the needs of this work (unpaid, but with so much love, like building barricades according to Charles Fourier) to collaborate with my project through Patreon. Thank you in advance the attention and support.

0 Comments

Richard P. Martin in his introductory study about Homer's Odyssey in the Edward McCrorie translation mentioned how some variation in the remaining Greek epic poem manuscripts opens a possibility of another kind of Odyssey. Because Athena, in the first canto, makes clear her intention to inspire the young Telemachus, son of Odysseus, to seek his father's whereabouts information between the Greek kings and military leaders who had returned from Troy. The cardinal points of this search, the “telemachy”, are well known: Sparta and Pylos, whose kings who gave testimonies were, respectively, Menelaus and Nestor. But in some surviving manuscripts Athena would instruct Telemachus to visit at least one more city, Crete, governed by Idomeneus. Martin then wonders if there would be a longer version of the Odyssey, which was lost in the Limbo of History, in some obscure process of textual revision probably caused by dark oscillation in which a portion – impossible to determine whether significant or irrelevant – of the poem totality was lost, probably forever. It is true that this loss survives somewhat in the and interstices more or less noticeable, in traces evoked by archaeological accuracy. Martin says, however, that there will always be something like “a provocation” in this residuum: the potential revival of the lost unknown and sectioned part, somewhere, revealing to us something new about Odyssey, allowing a new vision to the Homeric poem. The lost text stirs our curiosity and opens a breach in the stable perceptions of Literature, History, Knowledge, of the Universe. The lost, ignored, destroyed – in a word, potential – book seems to contain, at least for your achievable reader, a portion of divine revelation.

Interestingly enough the same ecstatic feeling on the discovery of a lost work of art, a landscape narrative truncated with blanks, is common in research and restorations made by film historians. Perhaps certain nearness to the Literature as idea through narrative conceptions make the cinematic restoration efforts more dramatic, indeed. Copies of rare and almost extinct movies have been found in basements, abandoned military wagons and other places even more unlikely. The extreme weariness of certain ancient films requires new procedures, technologies and approaches for this fragile, even flammable, material. A film like Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1926), for example, has a restorations history so long and complex since its launch until today (because a more complete version of Lang's film was found in 2008 at Buenos Aires Film Archive) that turns into a kind of contemporary legend and the search for the pieces of that film around the world in order to constitute a totality, the modern quest for the Holy Grail. Partially recovered films – some survived in the form of sequenced frames as the case of Bhezin Meadow (1935) directed by Sergei Eisenstein – excite the viewer's imagination in the same way as the records of a different telemachy excite Homer readers: what would be possible if that fragment there really being, the considerations about the consequences of such impossible discovery. A search for a meaning in a utopian form of discovery, the permanent reestablishment of a fragment of the past – or, at least, the evocation of what was lost – moves the archival explorers seeking to recover undeniable beauty files from the wreckage of repeated historical storms. In the process, they found obscure and esoteric references, evidence so disjointed and difficult to track so that apparently the field of historical research was lost and apparently the path is a deep swimming in the fragments of humanity's collective dream (or nightmare), embodied in an artistic shape. We might call the uncertain results of these endless investigations – ever incomplete because completeness of surveys a immense magnitude, such as the absolute recovery of the past – with a name: archival fictions. The fiction here is not only an extrapolation of historical reality given by narrative and mimetic resources. For authors such as Jorge Luis Borges, fictionalizing is to build a coherent, self-explanatory universe, methodically arranged by complex and peculiar laws, which can be shared with the everyday reality. Thus, in the Book of Imaginary Beings prologue, Borges proposed an interesting reflection on how the data from reality work to formar our perception of the wildlife at the zoo in a way far from a vision/experience of absolute terror for a child but rather a quiet journey full with wonder and even tenderness, so the trip to the zoo is usually listed as a childhood amusement. Borges then offers successive imaginative explanations for the zoo situation described by him, all at once valid and false, linked to common sense or the great traditions of philosophical thought from Plato to Schopenhauer. Fiction, accordingly, gets the curious status of a functional interpretative possibility of the reality captured by our senses and/or our consciousness since the core and raw data from reality would mean nothing without our interpretive activity. The researcher whose work relates to what we define here as archival fiction therefore works on the boundaries between reality, historical record, memory and fiction, especially when you need to describe or reconstruct some elements from the oblivion, such as biographies, trajectories, possible destinations. Therefore, the archival fictionist must exceed the literary discourse usual limits: the speculative essay runs through the borders of narrative, remembrance approaches the historical reflection, the description becomes, without warning, a poetic projection. An archival fiction archeology is a task that remains to be done, but we can say that one of his patrons is the aforementioned Jorge Luis Borges. Borges's creations put the instances of literary discourse on a unstable state, moving from a paradox to another paradox: in the borgean canon, there are imaginative fables that could be literary studies (as in the story "Pierre Menard, Author del Quijote"), philosophical essays with certain poetic resonance and narrative (Historia de la eternidad), cultural studies that plunge into the depths of imagination for new interactions and forms (Qué es el budismo?, with Alicia Jurado). Currently, some remarkable authors transiting through this equivocal universe noteworthy. Luiz Nazario, in Brazil, working with the records provided by the film, literary and philosophical imagination, especially when abandoned, overlooked or relegated to the unjust oblivion. In Europe, authors such as Mark Valentine (with two recent archival works, Wraiths and And I’d Be the King of China) and Andrew Condous (Letters from Oblivion) – whose themes are, respectively, the English decadence nineties in the last decade of the nineteenth century and the Romanian Surrealist group Infra-noir – conduct a complex recovery of obscure moments in literature, even emulating the style and perspective of their objects, seeking nearly the reproduction of definitely lost works and aborted projects. This is an impressive demonstration of the suggestive power of archival fiction, exploring the imagination and the human desire made in books (or films, or paints, or photographs), especially those missing on the fierce History skyline. At the gallery below, the frontispiece of Nestor Vítor's Signos, masterpiece of symbolist narrative in Brazil, and a brief book description by the Proceedings of the National Library (Anais da Biblioteca Nacional, vol. 87, 1967). This is such a rare book that only one copy is available for consultation. Article accomplished with the support of the PNAP-R Program at Fundação Biblioteca Nacional. Currently, the statement that the artistic avant-garde of the early twentieth century expanded the space and freedom of artistic inventions is almost a platitude. In this sense, the new possibilities and paths opened up by modernity in the Art also reached the narrative construction: after the realism developed throughout the nineteenth century achieve an amazing level of plot detail, even with the mimetic reproduction of nuances and peculiarities in perception, time, space, the modernity surpassed the need for systematic reproduction of the moment, the usual possibilities provided by common layers in everyday. Such creators have rediscovered the form of the plot without the myth of psychological, social and historical “need for depth", emphasizing repetition, ritualization, false paradoxes, erasure. In a word, returned in Space and Time for the powerful energies of myth, fairy tale, the legend, the supernatural. In this sense, the avant-garde artistic movements in the early twentieth century sought a curious ascendency, strains of certain antiquity, points of contact, missing links - a thriving and turbulent universe of narratives and representations was recovered within the huge and febrile, contradictory and conflicting tableau of aesthetic avant-gardist conceptions. It is in this complex context of rediscovery and conflict about this new territories we found the work of Roger Caillois (1913-1978).

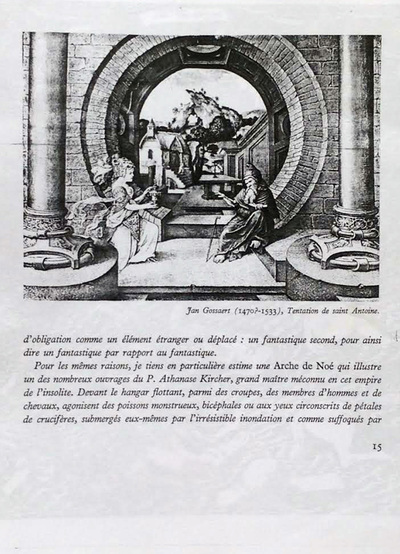

Caillois was a sui generis author that driving between sociology and literature, Latin America and the Europe, the game and the sacred: in the youth, was attracted into the orbit of the Surrealists but soon stood against the movement, sensing his own directions (as some any of his allies, Georges Bataille was the best known among them, in Acéphale magazine and the Collège de Sociologie). Escaping the Nazis, he left France in 1939 and went into exile in Argentina, where he remained until the end of World War II. In this active exile, he discovered the literary experiences developed by authors such as Jorge Luis Borges, Alejo Carpentier, Victoria Ocampo among many others that he would present to the French public in the collection of books (released by Gallimard) La Croix du Sud, already in the 1950s. Caillois sought to unify the experience that can not be reduced to everyday perception (the dream, the myth, the delirium, the supernatural, the random order) of the individual to the collective sphere, being one of the first analysts to seek a sociological, anthropological and political reading these seemingly fragmentary, inaccurate, absurd and unreadable data, so commonplace in the kind of experience that shatter the usual existence. In this sense, the notion of fantastic would be very helpful: very important in French literature, the fantastic began to be treated more differently by critics even in the 1950s, largely due to the avant-garde work (notably the Surrealists) with the term commodification, repositioned to qualify narratives with that peculiar effect of ambiguity and disruption. In this effort is inserted the short treatise of the fantastic art by Caillois, Au cœur du fantastique, published by Gallimard in 1965. The volume is a reflection and a beautiful tribute to the theme, but soon to be harshly criticized by another critic interested in the fantastic, Tzvetan Todorov in his Introduction à la littérature fantastique (1970). The bold analysis and discontinuous intuition employed by Caillois, despite its magnitude, would have no place in the geometrical view of Todorov structuralism. Putting Caillois and Lovecraft in the same compartment, Todorov simply qualifies both as "little serious critics” (so it would not be good to find serious critics defending the theories of both) that seek to define the fantastic in terms of cold-blooded reader or a vague notion of rupture/discontinuity of the "real world”. For the Bulgarian structuralist, it is vagueness, "fallacy of intentionality" and theoretical incompetence simultaneously the defect in these fragile competitors theoretical constructs. To illustrate his point of view, Todorov makes some brief quotes from the study of Caillois without mention that Au cœur du fantastique addresses figurative, not narrative issues. But this was no impediment to Todorov, although he probably should have read, impassive, the open of the first cailloisian approach. When trying to define an effect even difficult to express, passing literally before the eyes of a spectator contemplating a painting – and that Caillois knew, such an effect would have a different behavior in literary terms – the truth is that the old surrealist goes far beyond the structuralist. Already in the introduction Caillois propose the existence of a latent fantastic effect in the nature itself encoded in images and patterns, exemplified by this little critter, the mole nose-star, more suggestive to him than a Bosch hybrid. Much more than a break from everyday legality, Caillois fantastic resembles the rediscovery of these fringes defective in our fragmentary perception, the nonsense of a project to reduce the immaterial to nothing in the name of a principle of almighty reality. The Cailloisian fantastic is the mark of a strange imagery in Reality, shattering illusions of continuity and permanence. I found this wonderful book at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo (MAC-USP) library after to track it for years – a period without internet in which such findings, when it happened, was slowly enjoyed. Therefore, I have a copy, reliable and widely used. The book, to my knowledge, has never been reissued by Gallimard or any other publisher and also has no translation. Some curious mechanisms and tricks developed by the Modern Art allowed the reemergence of the polygraph character – the artist/scientist who tries to conquer various matters of Spirit and Form available on the known and unexplored connections between Culture and Nature territories. In general, this figure is usually represented by names such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Athanasius Kircher and Emanuel Swedenborg. The polygraphic view of the universe requires a singular displacement from some concrete problem (usually technological in nature) to more abstract layers of Culture, involving language and cognition: such displacement is the work of a polygraph complex flyover and flux which marks the language limits and possibilities, even when the "theorizing" side (since inception in multiple areas of knowledge necessarily leads to a continuous effort to theorizing and justification) shows absurd, outdated or invalid aspects. Essential to the Renaissance spirit, the polygraph reappears in the Twentieth Century incarnated by figures like the Italian Luigi Russolo, the Russian Velimir Khlebnikov, the Argentine Xul Solar or the Portuguese teacher, editor, graphic, philanthropist, philologist Paulo de Cantos (1872-1979). A contemporary of Portuguese modernists like Fernando Pessoa, Cantos built a work based on the imaginative dissemination of Science in books like Astrarium (1940) or O Homem Máquina (1930-36). But, in Cantos, the imagination always exceeds the momentum of systematic dissemination of Science and History in its atrocious or beneficial consequences or constructions, by the use of a creative typographic images and text recreations from edifying volumes by scientists and philosophers.

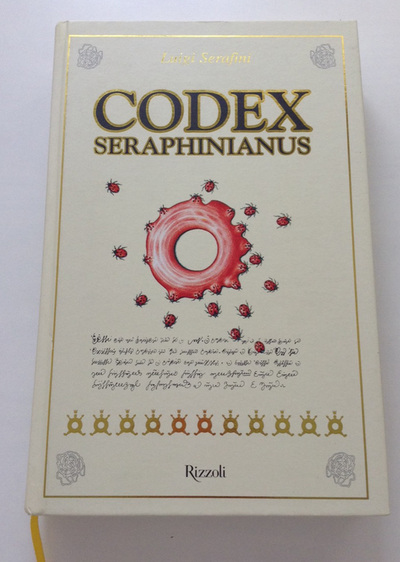

The "cantian" work – as it is known by its new researchers – invisible and ignored for long time, now beginning to be discovered by young Portuguese designers, delighted by the creative use of typographical and editorial elements in all the weird books published by Cantos. However, the original poetic language designed in complex configurations created by Cantos still await systematic analysis. Below, pictures of books Astrarium and Adagios/Maxims (1946), taken from articles on websites Montag and The Ressabiator. An interesting video produced and published by the magazine Público, addressing initiatives about rediscovery Paulo de Cantos works, can be seen here. The short story "La escritura del dios" by Jorge Luis Borges (published in the collection El Aleph, 1949) presents an intriguing plot: a priest (perhaps an Aztec priest) is trapped in a dark and gloomy dungeon by the new SPanish rulers, with only a moment of light by day when receiving meal and water. The only other being in prison is a jaguar (later called the Tiger), which shares with the priest the same narrow, dark and miserable space. The priest, plunged into despair and boredom, finds a task: to decode a secret message that his god wrote somewhere, in the large space of the Nature. With a insight, the priest discovers that the pattern of spots on the skin of the big cat in the cell is not random, but the encrypted message from god (as the title tells us, though the protagonist once mention "gods") and he, the chosen one to decipher it. A message of power, revenge and destruction, weapon of mass destruction that the priest, however, does not trigger simply because, after the discovery of the absolute, the human contingencies seem distant, incomprehensible, frivolous for him. The message of god, we know by the plot, is a total word, which encompasses the universe, what came before and what is after. But now imagine that god decided to write an encyclopedia, a volume that includes knowledge of various disciplines into a synthetic whole. It is likely that this encyclopedia follow some rules of the genre: perhaps a didactic division between the knowledge in areas like technological devices, geography, fauna, flora, history. Although this encyclopedia includes elements of our world – after all, also part of this god's creation – these elements do not appear in the spectrum of our usual understanding. Would be transfixed, perhaps even by the mood of such a god, a mood that could be, in any case, dark or sinister. Although we have made a brief and idle speculative exercise from a plot of Jorge Luis Borges, the truth is: this encyclopedia has already been created and its name is Codex Seraphinianus.

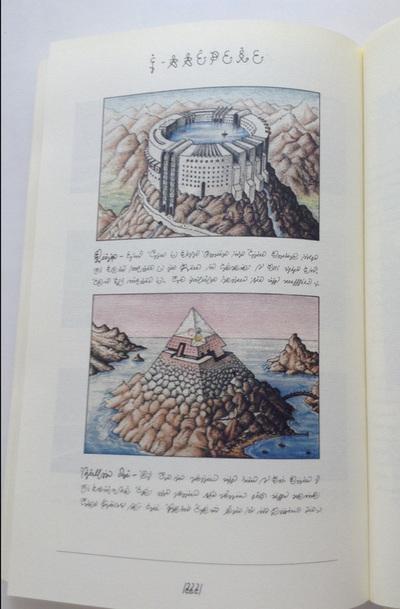

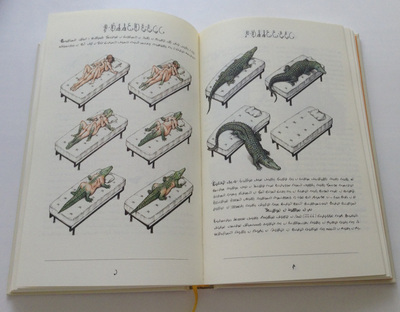

Originally a manuscript built by the Italian architect Luigi Serafini between 1976 and 1978 – the complex and whimsical pictographs, alien characters entirely invented, and the illustrations –, was published in 1981 by the luxurious and prestigious Franco Maria Ricci in two volumes, with a Italo Calvino introduction, "Orbis Pictus". The author's declared source was the enigmatic Voynich manuscript, fifteenth century codex in strange alphabet, never deciphered. The essayist Alberto Manguel, who was FMR editor in the early 1980s, was the one who received the bulky serafinian manuscript by mail. In his book A History of Reading, Manguel recounts his encounter with this strange manuscript, calling the work "one of the most curious examples of an illustrated book I know", created "entirely of invented words and pictures", something that forces the reader to a process of decoding the text without the aid of any formalized natural language. It is an invitation to the reader to transform the usual reading activity into a dynamic process of interpretation/creation of a young, wild and throbbing universe. Thus, the elements of the book are not entirely alien: it is possible to recognize human figures (the whole or cut into pieces, sectioned to perform new functions: eyes that turn into fish, for example), animals, plants, technologies (for cars with melted parts or made of unusual materials) etc. You can also see, in the same manner, that the strange alphabet is provided with a organization process with elements in common to human languages: clauses, sentences, titles and so on. However, this perception does not contribute to the advancement of understanding, capturing or establishment of the text definitive meaning. Instead, gave rise to ambiguity. So, if we can find some recurrent features in the serafinian images and text – for example, the principles of fusion and transformation – we soon discovered that there are other principles permanently conflicting with, and the irony that runs through these pages just neutralizes categorical definition. Franco Maria Ricci has released two editions of the book (in two volumes and as a single volume), both sold out and reaching astronomical prices on specialized sites and bookstores worldwide. Later editions of other publishing houses are rare, all sold out, as the versions by Prestel (Germany) or Abbeville Press (USA). The latest edition (first issue came out in 2006 and the second in 2008) is the Milanese Rizzoli, much cheaper than usual for the luxurious album. Serafini, meanwhile, continued producing beautifully illustrated albums, like Pulcinellopedia (under the pseudonym P. Cetrullo) or an illustrated version of Les Histoires Naturelles by Jules Renard. This books are even more inaccessible and invisible, rare pleasures for rich bibliophiles. Anyway, it is curious that Codex Seraphinianus has gained cult status on the Internet with amazed articles on websites and publications like The Believer or Dangerous Minds, given the limited and short publishing history and the type of challenging "reading" activity proposed by this book. Maybe it's the fact that the reading of this strange encyclopedia whose content is a knowledge supposedly universal anticipate what we see at Internet, a entropy whose chaotic surface is unfortunately far from possessing the same wry humor. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed