|

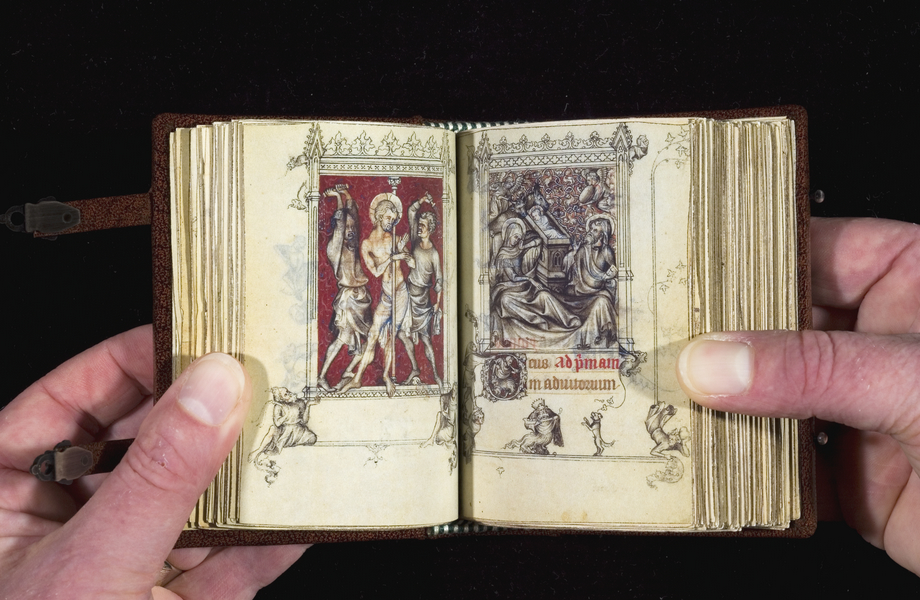

The Hours of Jeanne D’Evreux (photo by medievalfragments). A whole new mythology could be developed based on the possible books, those who have been imagined but never written. Or lost forever in one of these History’s plot changes, always cruel to the weakness of the imagination. In this sense, there is a tale by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges that appears to offer a terribly enticing prospect for any writer. This is "El milagro secreto” (The Scret Miracle) part of the “Artifícios” section in his Ficciones (1944), which tells the story of a poet who, after quick conviction by a Nazi court, is facing a firing squad. He worked in a particularly difficult tragedy and his desire would be finish it before the bullets of his executioners rip apart his body. It was obviously a vain hope, but some divinity heard the poet and awarded him an extra year between the time of shooting and the impact of bullets, so he concluded his work. This was done and as soon as the last fixes were completed, the bullets were put in motion again. The poet, protagonist of the story, did not have time or possibility to realize his definitive work on an appropriate editorial format; only his memory and the deity who heard him would know the content of what was projected in his mind. So the author and narrator, Borges, provides the reader with not a reproduction of this unusual work, inaccessible and not registered, but its uncommon route. In this sense, Mark Valentine offers to the reader the same in his Wraiths – the winding path, unique and complex that never got to take shape or become visible.

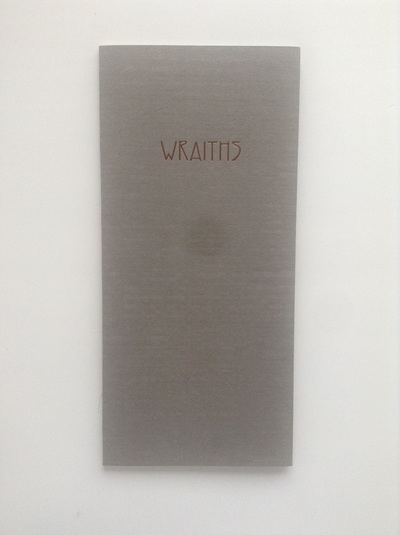

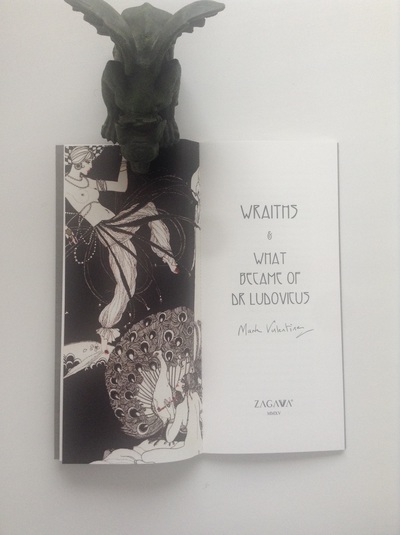

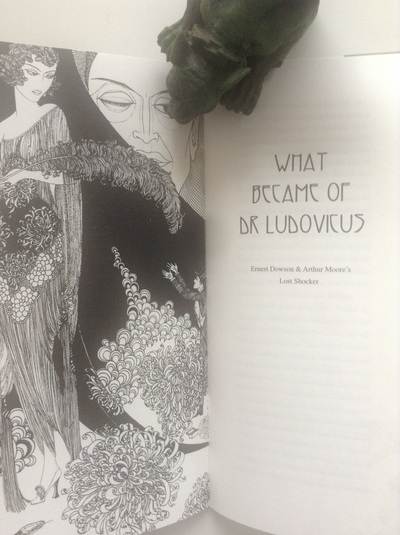

The essays of Mark Valentine is vibrant, innovative and suggestive. One aspect of these essays, no doubt, is the approach/recreation of lost, unfinished, invisible literary works. In Wraiths, there are two essays focusing on the specific form of non-existent creation and not materialized potential that entices the imagination of a very specific kind of animal – the bibliophile, a kind of people who nurtures this obsessed, sometimes excruciating, fascination on book as object, form, idea. The first essay, "Wraiths", deals with the poetry books that were probably produced at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century in England, but that apparently does not exist. This time was populated by books of short poems, precious little jewels of the publishing industry, but not all have this essential embodiment, the final book form. The books of imaginary poems described by Valentine are as complicated mirages, whose existence is attested even by witnesses, but that vanished and left no trace. Valentine, in this first essay, use these testimonies, these indirect evidence to handle such invisible corpus; it is an intelligent methodology, because the indirect evocations bring the reader something unusual about the lives of the kind of dematerialized masterpieces creators. This evocation provides, by a paradox of representation, something like a glimpse of the lost poems. Cause, in fact, such non-existent creations go even further than these sparse and vaporous sonnets that Mallarmé wrote for printing on fans. The authors of lost works reached something like the accomplishment of an imagination utopia: the poetic construction as short, soft, sophisticated structure, which is diluted in ominous or happy fragments in the very existence of the poet and his time. The second essay, "What Became of Dr. Ludovicus", deals with the creation not performed adventure in a even more intricate level: a lost novel, which was written by four hands between Ernst Dowson and Arthur Moore. It was a "shocker", which was the way the Victorians termed novels with bizarre, disturbing and/or supernatural central elements. The essay follows the production of the novel in the letters exchanged between the two authors; the level of detail of this production process, evoked by Valentine, is quite large, including details such as the use of a notebook with shared writings that both authors employed to write the chapters. The reader thus follows the development (sometimes problematic) of each chapter and the fate of the finished material, systematically rejected wherever the authors try to publish it. Would be a fair rejection, given the quality, editorial or myopia, as often before a interesting material? Valentine leaves this question open, stressing however – with his bibliophile soul – how interesting it would be if the book had been published, knowing its narrative and its creation process, both seemingly rich and tumultuous. This is perhaps the most obvious essence of the Wraiths, the connecting link between the two essays: the desire for the existence of a book, in a way, can make the reader itself (which already became a researcher investigating the tracks of his passion here and there), by a sort of evocative magic, perform this conjuring of a lost book that makes out of nowhere appears something. As a book, Wraiths is a delicate and precious object, indeed a beautiful tribute to the fin de siècle editorial art. Only the title appears in golden on the cover – a sinuous font seems to mark here at the same time daring and restraint, the only distinctive feature in a rough and gray paper, reminiscent of the stone, a texture little polished but rich in nuances. The two Ronald Balfour illustrations that open the essays seem to evoke in a starkly and not overloaded way the Victorian era. Interestingly, the Mark Valentine book today is partly invisible – the Zagava publisher reports that the print run of 50 copies is already out of print. Although the essays can be found in other books (notably, the excellent collection of essays published by Tartarus Press, Haunted by Books) the preciousness of this little booklet, so slim that could disappear at any moment, it is irreplaceable.

0 Comments

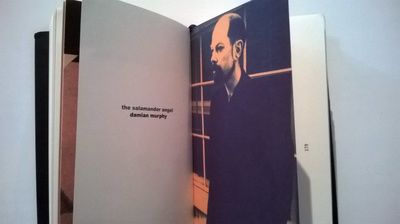

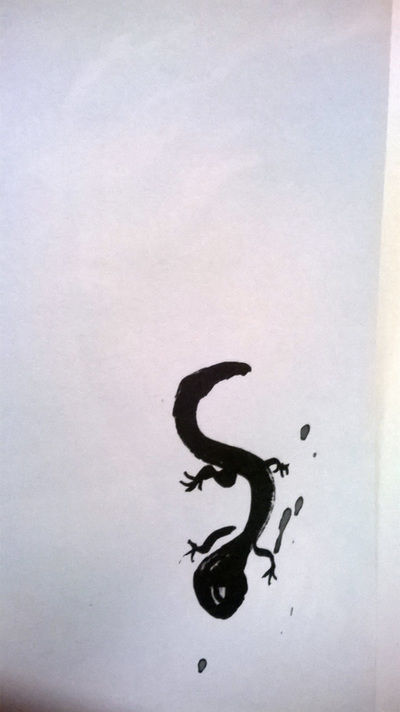

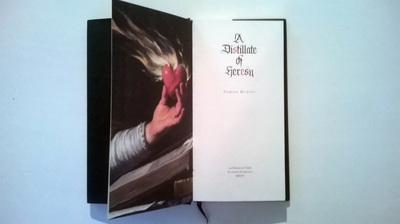

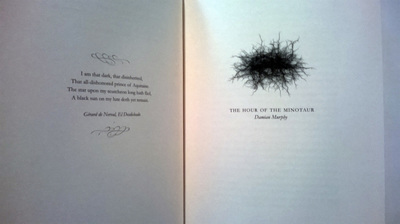

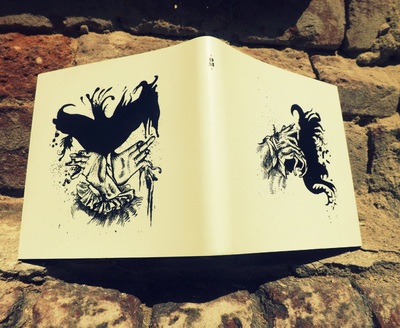

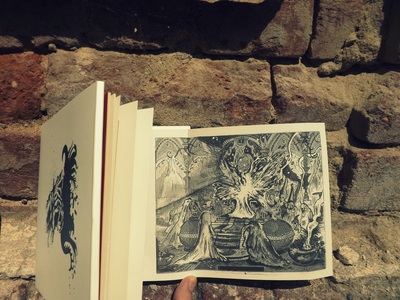

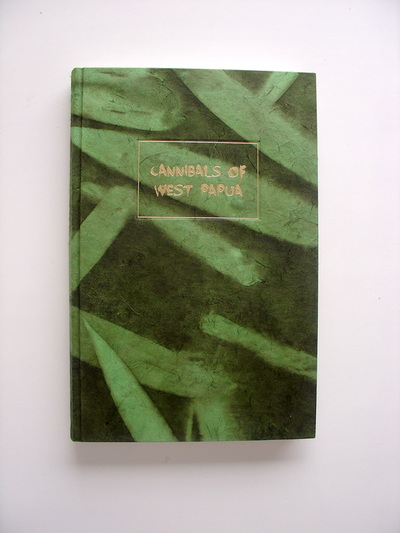

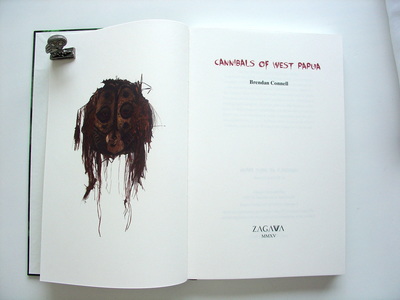

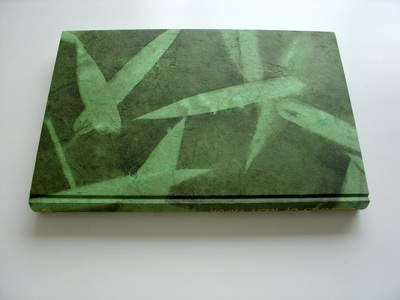

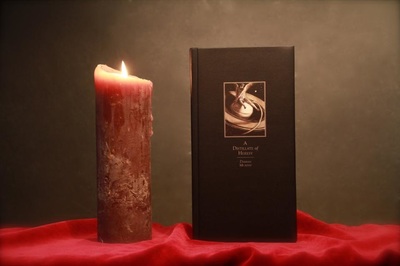

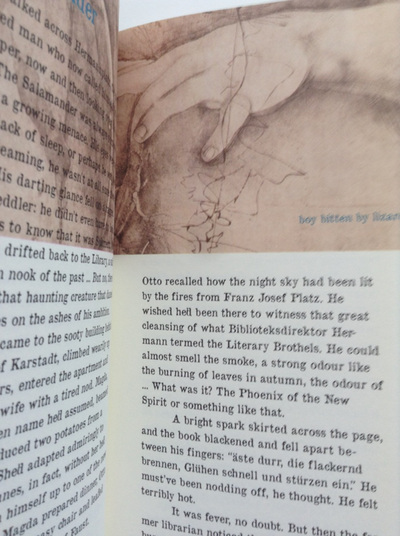

I sit down before a book: the jacket is entirely black, slightly glossy. I can hardly distinguish his name on the spine or the front of the jacket but it is possible to read the title, A Distillate of Heresy, written by Damian Murphy. The only image at the jacket, besides the tiny publishing house logo on the spine, is a small illustration of an angel sitting on Saturn; the predominant color, again, is black, now mixed to a pale golden, a necessary hue to build the volume illusion in the image. I pull out the jacket to contemplate the book in its nakedness: the cover, made of fabric, is also black, unadorned and without indication of any kind whatsoever. This dark predominance makes the reader's head go round: would be before a Grimoire, a clandestine book? A printed material that was, somehow forbidden or at least profane, demonic? The content would be near the blackness that dominates the external surface of the book? But here we come to the guard of the book: the black finally gives way to red shades in profusion, an abstract marbled effect, deeply significant because alludes to ancient books, lost in libraries and secondhand bookshops. So we are facing a more complex sense of purpose which only the outside design organization of a book: the blackness of the cover and dust jacket gives way to bright red tones of the guard in a kind of sequence, intense and dull colors in a contradictory shadow play, though potentially complementary in a ceremonial sense. For this book deals with ceremonies in so many aspects. But it is too early to discuss its contents. Soon after the guard, a stylized, almost typographic image – the salamander (a creation by Sorina Vazelina) in the form of an "S, a minimalist figure that seems to reach, despite its simplicity, the formalization found in a letter or in some hieroglyphs. After all, this "S" guard the twisting sense of the fantastic animal (the salamander) and seems to communicate with the book's narratives, dealing with mistakes, coincidences and chance encounters that generate ceremonial and ritualistic effects. This calligraphic image seems to contrast with the typography of the title page and the elaborate subsequent image of a hand holding a heart on fire, cut in big closeup of a much larger and more complex pictorial composition; this is the Saint Augustine (1645-1650), a painting by the Baroque Philippe de Champaigne, reproduced above. In the image of Champaigne, the saint is in his study room, apparently enjoying a moment of enlightenment after intense intellectual work. The ecstatic eyes of the saint converge on the veritas shining like a small sun in the upper left corner as his hands holding a pen and a heart on fire by divine inspiration. Highlighting just the hand that holds the heart in flames, the Murphy's book graphic work displaces the intellectual saint imagery of its usual position; there is no veritas that illuminates everything, even the spatial location and the general background of the image, but only the bloody organ on fire, something spiritual and carnal, even cruel, but certainly ritualistic. As the narratives, these brief images place in the space of the book paratexts seems to indicate that the conventional ways hide many shortcuts and unknown routes far from salvation and enlightenment for anyone that discovers these kind of paths. There are brief texts, epigraphs that prepare the reader for the actual stories. In one of these epigraphs, we read that the book is intended "For the heretics, the few, the outlaws, those who turned to face the Moon rather the Sun." There are no images in the rest of the book, but they would be unnecessary: the form was established by this presentation that works an organic link between text, images, layout, design aesthetics and essence of the narrative. As written by the researcher Évanghélia Stead in another context: "Pictures and prints, folds, covers and bindings, ornaments, graphics and typography, even the ink and the letters, the insects that go through the desert of the paper and were endowed with an intellectual, poetic and sensual sense." Damian Murphy, in this sense, is a unique narrator to handle unusual elements in the white desert of the paper, turning it into a dense forest of signs: his stories have a ritualistic sense, a game between objects (everyday or not) and chance, each of this parts playing essential functions. His protagonists are unique characters, whose life follows its own meaning in contrast to the more mundane aspect of existence, priests or shamans seeking ritualistic events in every little chance of escape. And the editions released by the publishers Zagava and Ex Occident Press, complete the complex sense of these narratives moving the fluidity of the reality electrified by symbolic and mythical meanings. The first tale of the book, "The Book of Alabaster", is about a recluse who collects in his tower, unique objects like an old video game cartridge whose name is the title of the story. In the first sentence, a synthesis of the Murphy's aesthetic and narrative vision: "Stefan lived alone in the lookout tower." There is something timeless in this short sentence, whose center is the expression lookout tower, a type of military construction which generally refers to the primeval times, to the Middle Ages. This early disorientation of the reader possibly disappear in the flow of the plot, but never so as to realize a well-defined and clear universe and/or scenery. For Murphy narratives develop in an abstract plan, in which physical landmarks easily get lost and confused with psychic perception or mythic space in its roundness, infinity and ritualistic unfolding. The subsequent stories of A Distillate of Heresy develops in different directions this proposal of a physical universe which contains his double, difficult to define or perceive with the necessary clarity required by mimetic realism, culminating in "Permutations of the Citadel", a tale in which the fictional reality seems continually transmute around the characters. These are games and pursuits involving daily life opening new possibilities not only for the initiation rite, but also for sacrifice, with the view at the same time dark and desirable of endless territories under our cities, places where the evocation potential hellish seems relatively easy. The city is a theme dear to Murphy: a twilight and tentacular entity whose daytime and everyday appearance is just one of its many labyrinthine manifestations. Murphy's subsequent productions – actually the novel "The Salamander Angel", published in Infra Noir collection, preceded the tales of A Distillate of Heresy in a few months – as the novels The Imperishable Sacraments and "The Hour of Minotaur" (penultimate narrative the collection The Gift of Kos'mos Cometh!) had been exploring new ways in the infinite possibilities of ritualistic and ludic combination in terms of narrative. One of these ways – very well developed in the latest Murphy's novel, The Exaltation of Minotaur – is precisely the philosophical dialogue that unfolds in intricate structured combinations for the stories turning around symbolic elements that allow the first narrative chapters, "An Incident in the House of Destiny" to use titles that allude to archetypal forms: the bureaucrat, the anarchist, the vision, catastrophe. Even the division between different literary genre looks inappropriate in the narratives of The Exaltation of Minotaur, complex forms between the short story and the novel intertwine in obsessive detail, cyclical aspects endow the characters ritualized activities of meaning layers. Murphy, accordingly, performs multiple evocations every narrative; perhaps some of the evoked names can be recognized by the reader: Alain Robbe-Grillet and J. K. Huysmans, somehow. But this is only the surface: the nuances and consequences of Murphy's stories are situated in an opaque, indefinable and dangerous region we usually call imagination, a place that is not always easily accessible. Some of the photos below (the last three, from the books The Imperishable Sacraments and The Exaltation of Minotaur, respectively) were kindly provided by Dan Ghetu. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, in a particularly fierce aphorism of their Dialectic of Enlightment latter section – a treatise about the rationality booby traps – saw some similarities between the haruspex in a pagan altar and the professor working on a dissecting table of a ultra-modern laboratory. For the two German philosophers both the priest and the scientist represents the Man and the Humanity devoted to the ecstatic observation of Nature in bloody agony, slowly tasting the perverse pleasure that such activity can provide. Of course, it is not the suffering of Nature as a totality, since the focus is on the potential and preferred victims, seen as the weakest links in the terrible chains of natural and social logic – captured animals, the natural sources with easy access, peaceful and isolated communities, segregated human groups, women – chosen for sacrifice. When faced all the blood, viscera, and the torment of open wounds, the owners of knowledge (scientific or ritualistic) seek signs, evidence, portents. So this brief aphorism, titled “Man and beast”, presents the thesis, central to Adorno and Horkheimer philosophy, that the brutal and fearful exploitation of Nature reflects the brutalization of man from the remotest origin, the most distant historical sign and myth. The devastated Nature and the Humanity enslaved reflected each other, lighting points, details and degrading aspects. Thus, the fierce and brutal Cannibals of West Papua, a novel by Brendan Connell recently launched by Zagava Press not only takes up the thesis of the philosophers like Adorno and Horkheimer as the turns inside out their propositions, thanks to the almost unlimited resources of an intricate and fluid narrative, which gives the reader the vertiginous sense of risk, as we should possibly feel when entering an unknown and uncivilized jungle.

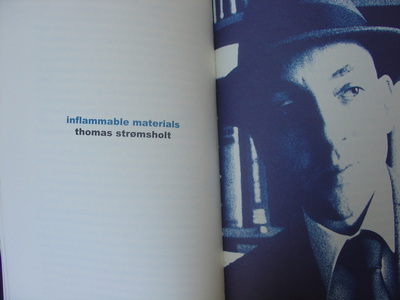

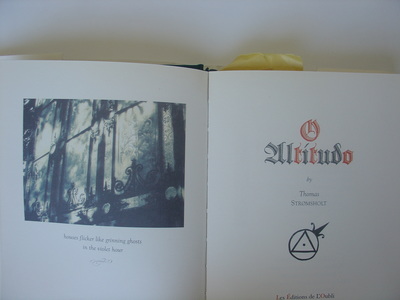

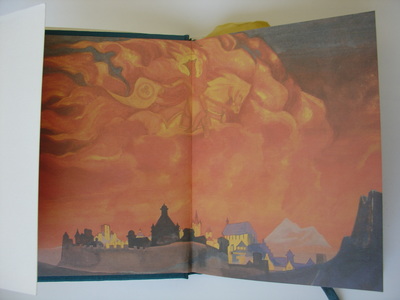

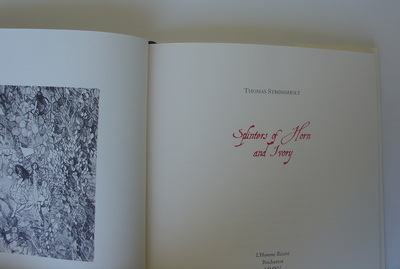

On your journey to South America in 1832, Charles Darwin was deeply impressed with a native tribe of Tierra del Fuego living in a primitive state bordering the unthinkable to the young Victorian naturalist: “One can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow-creatures, and inhabitants of the same world”. This tribe, the Selk'nam, had a kind of photographic testament in a brief peaceful moment before the extinction thanks to the Martin Gusinde, an Austrian priest, between 1918 and 1924 (these photographs were published in the book The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego). The Gusinde arduous struggle to preserve at least the image and the memory of the Selk'nam conflicted with the genocidal fury of Julius Popper, a Romanian engineer who performed manhunts since the early 1890s with the intention of pacifying the territory, facilitating the work of miners and ranchers. It would not surprise if the Patagonian Indian hunters – adepts, by the way, of the documentary photography, especially to record the dead human prey – imagined that the Selk'nams, with their stylized and complex rituals, were cannibals, a powerful argument to help in the rationalization of murders. A hypothetical meeting between Gusinde and Popper (impossible, for the second died peaceful in 1893), in turn, would be an interesting opportunity to put face to face antagonistic perceptions of savagery, civilization, progress, dialogue, peace. The Cannibals of West Papua central characters, Don Ramiro Duarte and Fr. Massimo Tetrazzini embody the extreme positions of civilizational scope in the similar manner as Popper/Guslinde – the first, preaching the forced conversion and the imposition of industrial rationality; the second, adept at a less radical position, searching for some understanding with the natives. This does not mean, however, that the novel is based on manicheistic oppositions; apart from the secondary characters contributed with some nuances to the question (as Sergio Manuel, the helicopter pilot, or Vali, a native of Patntrm tribe) the position of the two main characters is far from solid. An initiatory path is imposed on those two Catholic priests, a way that the reader follows anxiously, though that's not to say that the Connell’s novel is a kind of conventional thriller in the same pattern as The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan. It is a narrative much more complex, which approximates the Hades of Dantesque feature to the eastern Buddhist hells, the prose of gothic horror to the criticism of the Nature and Culture destruction by the illicit interests, the ethnographic poetry of oral indigenous people to the visions about the infernal gears of Natural World worthy of the Fitzcarraldo, the Werner Herzog movie. The unique structure of the Connell's fiction comes in a flash on the first page of the novel, when Don Ramiro notes terrified “that vast expanse of green, deceptively beautiful, without any signs of highways, housing or civilization – instead a flowing sea of hypnotic violence." Cannibals of West Papua is a sequel of a previous novel, involving one of the protagonists (Fr. Massimo Tetrazzini), The Translation of Father Torturo (Prime Books, 2005). However, despite this relationship of continuity, clear at times in passages related to the past of Fr. Massimo, the new novel works very well alone. With the focus on the enhancing a wide evocative universe that goes far beyond the West Papua, Connell elegantly avoids the pitfalls of novels serialization. Such elegance is expressed in every detail of the novel, from the language to the creation of a timeless atmosphere, despite all the signs of modernity that appear particularly in the novel's introductory four chapters. After the discovery of the isolated and aggressive tribe of Up-Rivers in the chapter V, the plot leaves any strictly realistic or casuistry restriction to plunge into a chaotic universe full of violence and supernatural (a exquisitely and unique supernatural proposition, in fact), although without losing the subtlety and the systematic development of the narrative structures. As in The Day of Creation or The Crystal World, both by J, G. Ballard, Connell's novel is crisscrossed by two conflicting principles: the reversal and the hybridization tendencies. The central characters, in their successive and agonizing metamorphoses, put both principles in collision and conflict. Not coincidentally, the tradition (in pictorial or narrative terms) enshrines these two foundation concepts to the characterization of hell and thanks to the old and new potentates of the Earth (which are the subject of the author's disgust and anger in the epigraph that opened the book) our planet acquires the features of a continuous and exquisitely Hades, bureaucratized and inescapable, as described in detail by the Connell’s sulphureous prose. The book as an object, produced by Jonas Ploeger of Zagava Press, is intensely beautiful. There are two editions with covers based in the random and unique patterns of leaves – one of this editions with only 26 copies in leather. These patterns suggest, both in visual and tactile terms, a dense, mysterious rainforest. It is impossible not to continuously contemplate, in the reading intervals, this strange and beautiful cover, in search of some hypnotic revelation. Each edition is signed by the author and, although there is no illustrations – just an amazing mask appears in the first pages of the book – the general layout and the paper have a perfect balance, which greatly facilitates the reading. A simple and competent editorial jewelry, the perfect way for a novel that affects the reader, as described by Kafka, like an ax blow. This review was accomplished support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). In the siege to the city of Tyre, facing fierce resistance, Alexander the Great had a dream with a satyr dancing furiously. The Alexander official oneirocritique, Aristander conducted a astute reading of the dream, saying that the satyr was not a symbol or an image but a phrase: “sa Tyros”, Tyre is yours. The interpretation nears the dream field and transforms the oneiric activity, surpassing the mere image of vague symbolism. The old dream of Alexander and it’s translation by Aristander could have come from any of the Thomas Strømsholt tales, an extraordinary player, performer, creator and replicator of dreams. His books, O Altitudo, “Inflammable Materials” (from the collection Infra Noir) and Splinters of Horn and Ivory have a curious resonance between the beauty of editorial solutions and the wonder of narrative constructions. The brief narratives of this books – close to the Baudelaire petits poèmes en prose and the surrealists récits, but far away because the unique formal and narrative approach by Strømsholt – changes before our eyes full with astonishment, as the everyday dream that goes beyond the hours of sleep and remains vivid in our consciousness.

Most of the pieces were fashioned from entries in my dream journal, recordings of dreams that only needed a little polishing to make them enjoyable (I hope), while others were the daydreamy germinations of whatever came to my mind at the moment of writing, hence the shifts in tone, style and content. But I did work toward a unifying theme for the book, that theme being, as you so correctly identify it, metamorphosis of some kind or other. We tend to view the world as made up of hard and clearly delineated objects and ourselves as solid bodies with fixed identities. A whole other way of viewing existence is presented in the Metamorphoses, a poem that I love very much and keep returning to. Not only does Ovid tell of “bodies changed to various forms” but the poem itself has a transformative power: in the end the poet is made immortal, transmuted. I believe that art – which is always a transformation of nothing into something or of something into something else – has the power to effect and change reality. “Coccinella” may be read as the possibility of transcending such notions as identity, gender and, ultimately, the human condition.

In the “The Wandering Thesauri,” which owes something to the universal libraries of Kurd Laßwitz and Borges (among others), there’s an allusion to Dada and their sane revolt in an absurd and ruined world run by lawful thieves and mass murderers. It’s in the nature of art to transgress in one way or another. Some books are cloaked criminals intent on knifing, subverting and perverting our hegemonies, categories and preconceptions; this, it seems to me, is a very noble endeavour. Even the most innocent looking books may contain some form of transgression even if it is only to engage the reader in an imaginary world for a brief period of time, a sort of temporary lapse of sanity. In my “commonplace book” there are many quotations extracted from Machen’s immensely diverse works. One quotation, pertinent to your question, reads: “For literature, as I see it, is the art of describing the indescribable; the art of exhibiting symbols which may hint at the ineffable mysteries behind them; the art of the veil, which reveals what it conceals.” Machen’s style is one of great clarity and measured obscurity. As we’ve all experienced, twilight and darkness activate the senses wonderfully; by leaving hints and suggestions the writer encourages the reader to fill in blank spaces, to populate the shadows and to slip through the cracks.

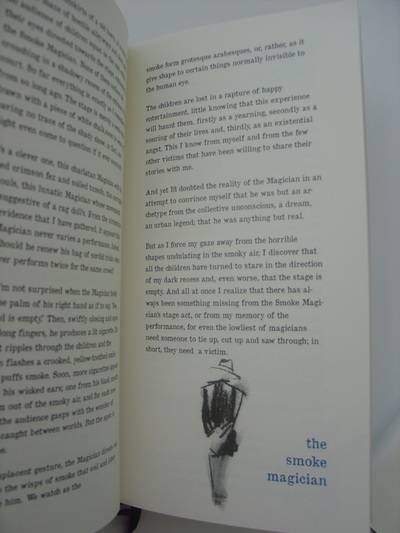

In the case of Inflammable Materials, if I remember correctly, Dan Ghetu had specifically asked for very short prose pieces. I’d made a few attempts in that style before, and although not quite successful, it was enjoyable. Picture, if you will, a masticating cow and you’ve got a good illustration of how I usually approach a short story, writing draft upon draft, endlessly revising, etc. But as I said above, the vignettes are mostly impromptu pieces even if it’ll take hours, a whole day maybe, before a particular vignette is finished. Perhaps the almost frivolous spontaneity of their conception loosens the constraints of my usual conventional manner, the style shaping the content. That aside, I love brief narratives and prose poems. The latter, Huysmans tells us, is Des Esseintes’ favourite form of literature because it should ”contain within its small compass and in concentrated form the substance of a novel, while dispensing with the latter’s long-winded analyses and superfluous descriptions”. Huysmans, no stranger to luscious verbosity, may be having fun at his own expense here. It is often in the ”long-winded analyses and superfluous descriptions” that the novel really comes to life; cut it away and you’re left with an empty house, a barren protestant church rather than a gorgeous cathedral. Certainly, there is no need to weigh the novel against the prose poem in order to appreciate the latter. A short piece may evoke or suggest a greatness that belies its scant length just like an impressionistic piano piece may linger in our minds as long as a symphony, albeit in a more vague fashion. Of the pieces in Inflammable Materials and Splinters only a few approach the prose poem in style or tone. The operative word here being “approach,” for writing poetry is far beyond whatever literary skills I may have. I prefer calling these prose pieces vignettes which is just a fancy name for prose below 1000-1500 words. That said, the prose poem and the vignette might share the same objectives: to capture or exteriorise a flash of illumination, compress a dream to its essentials, convey a joke or anecdote, etc. The very briefness of the vignette is an attraction too. I might be dead tomorrow but at least there’s a chance that I’ll be able to complete a vignette before day’s end (or so I tell myself). Although this kind of reasoning is quite absurd (followed to its logical conclusion one ought to refrain from initiating any action whatsoever), it is a comforting thought both as a writer and as a reader. To leave things unfinished is as deplorable a prospect as it is probably unavoidable.

I’m delighted that “The Legend of Melancholic Prince” should evoke a marriage between Wilde and Baudelaire; I never thought of it that way but there’s certainly a whiff of decadence about it (and “The Glowing Heart” as well). The pop music references are far more explicit. Bowie’s music, which has been in my ears since I was about 10 years old, is a continual influence on my writing; a single line of his can conjure up whole new ideas and visions. As for Leonard Cohen, he just appeared in my dreams three nights in a row; in each dream he delivered an aphorism or bon mot (spoken in his wonderful smoky voice). But I’m evading your question for the simple fact that I do not know how to answer it. I suppose that some references just occur as a natural element in the fabric of the story, while others are carefully weaved into the story in order to pay tribute, acknowledge an influence, or to suggest possible readings to the reader.

“No bridge exists between the transcendental world and nature’s reality,” as Bruno Schulz so succinctly put it. Schultz, in fact, is one of the most accomplished oneiric authors I can think of. In his stories the common Platonic-Cartesian dualism dissolves: reality is transmuted, made phantasmagorical, made real. I cannot claim Schulz as an influence though, only as a model. To speak of influences is always a dubious matter. My perception of dreams is most likely a hodgepodge of philosophers and authors, some popular, some odd, and, dating back years, some forgotten. Dreams seeping into waking, blurring or corroding the apparent boundaries between the two states are certainly a motif frequently met in literature. Good stories share with dreams the quality of being perceived or experienced as truer than what occurs in what is usually denominated “reality.”

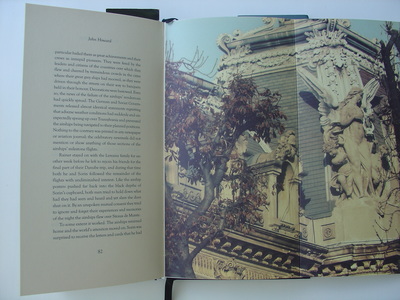

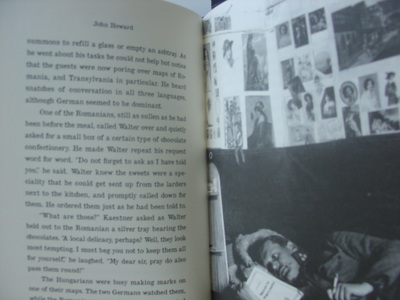

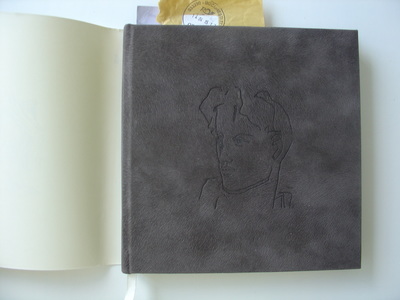

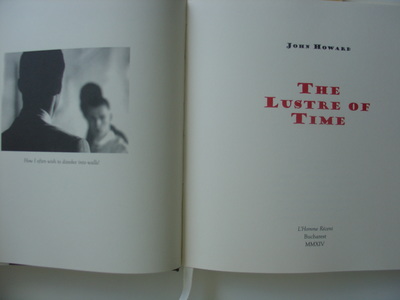

When or if the right idea for a more extensive or substantial story presents itself, I’d probably follow its scents like a lovesick dog even though the transubstantiation of idea into words is too often an extremely frustrating process that ends in failure and despair. My one and only ambition is to write a good story – just one – and the length of that story doesn’t really matter. Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). In a recent past, a very large History of the World seemed a good idea: authors like HG Wells sought audacious narrative synthesis of the multilayered historical process. The efforts were elegant or eventually reductionist in the task of extracting a logic in the History, a process that has certain essential disorder, as said Jean-Paul Sartre. In fact, a possible criticism about universal stories, perhaps the most striking critic, is precisely the approach of historical fact, because the universal historian appreciates the wonder facts and great names in a seemingly continuous line of progress. However, there is another History, populated by people and events unjustly ignored, remote or marginalized. This historical otherness, that is often not even known, emerges in a unique form in the works of John Howard. The marvelous fiction of Howard addresses fantastical phenomena and philosophical questions in the edges of our history and cognitive universe – sometimes in totally imaginary regions, as is the case of his most significant topographical creation, Steaua de Munte, a exhilarating region of imaginary Romania that can be visited in his latest novel, The Lustre of Time. Even the supernatural in Howard creations is subtle one, almost imperceptible – the uncertainty is the poetic weapon of John Howard in his antithesis of universal history, an imaginary history, unique and terrible.

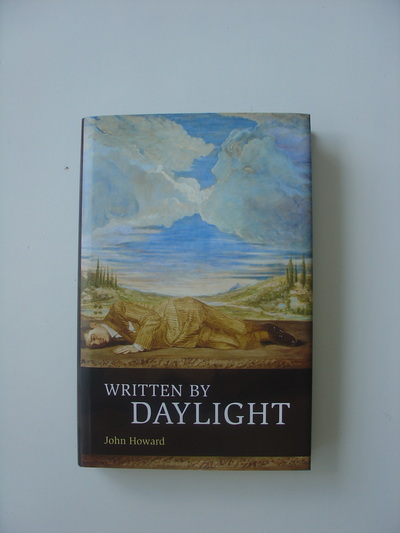

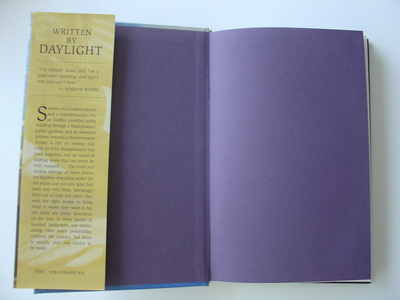

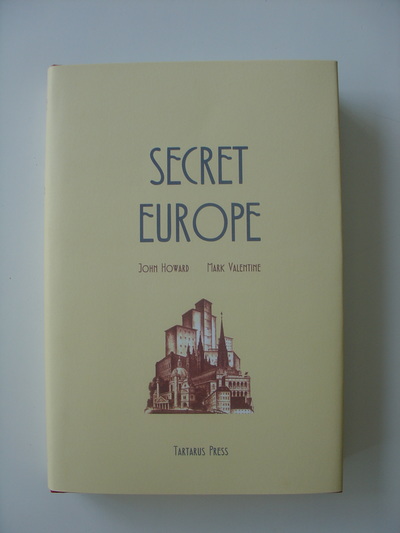

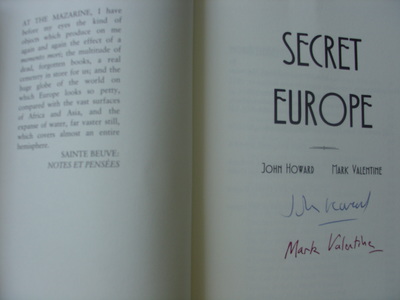

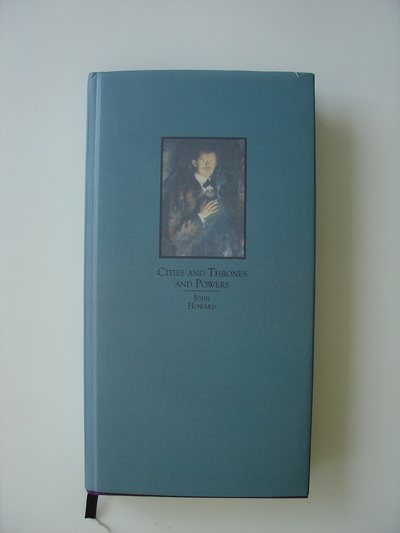

A very particular approach to urban topology, including the development of an entirely fictional town, Steaua de Munte, emerges in your works. This imaginary city is extraordinary, an entity that continuously develops itself over several short stories and novels, with its cafes, hotels, universities, hills, houses, buildings. It's an imaginary space equally or more extraordinary that William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County or Arkham by H. P. Lovecraft. So what would be the point of creating a fictional territory in such a distant place, covered in a peculiar picturesque mythology, Romania? What have been your sources and conceptual and imagery sources for the construction of Steaua de Munte? Modern Romanian history has interested me ever since I came across a contemporary account in John Gunther’s Inside Europe (1936, and subsequently much revised and reprinted). This was when I was still just a teenager and there seemed no reason for Communist rule behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ not to last for ever. I found Gunther’s portrait of the country as it had been nearly fifty years before my time to be utterly fascinating. Romanian politics were byzantine, Ruritanian, and murderous. And the country’s leaders – especially the flamboyant king, Carol II – seemed larger than life. John Gunther was an American newspaper reporter, a foreign correspondent in Europe for many years before and after World War II. He became one of those authors whose books I always look for. I have a shelf of them. I never forgot Gunther’s vivid and accurate summaries, and when Ceausescu and the other Communist leaders fell, it came as no great surprise to find their countries carrying on, in many ways, from where they had left off in the 1940s. There is so much in the histories of that part of Europe which seems almost operatic or something out of a television drama – if it had not been real, it could only be believed as fiction. But that is easy for an outsider such as me to say: these people were also responsible for ruining the lives of so many of their people. Fiction can examine the dark places – and should do. The opportunity to visit Romania came in 2009. The previous year Dan Ghetu’s Ex Occidente Press of Bucharest had published The Rite of Trebizond and Other Tales, a collection of stories mostly written in collaboration with Mark Valentine. Dan had read “The White Solander” – one of the tales of The Connoisseur that Mark and I had written together, and which had a Romanian background. Then Dan invited Mark and Jo Valentine and me to visit Romania. Dan and his wife were generous and painstaking hosts, driving us around much of the country in an exhilarating tour which nevertheless ended all too quickly and still left too many wonderful places unvisited. We crossed the mountains into Transylvania and stayed in the old cities of Sibiu and Sighisoara, and these were the main sources for my city of Steaua de Munte. But in most respects Steaua de Munte is a unique and special place, not dependent on anywhere else, and is what I, as sole proprietor, choose to make it – and remake it. Novels and series of stories set against a common background have always appealed to me, especially when the setting develops and changes, with various different aspects being revealed at various times, and yet which also leaves much to the reader’s imagination. Characters come and go (and families and relationships are vital) but the background scene, even when it changes, does provide a level of continuity against which new stories unfold and have consequences for the unwritten future. The protagonist of "The Fatal Vision" (the longest narrative of the book Cities and Thrones and Powers) and The Lustre of Time, Dr. Cristian Luca, embodies something of the archetypal figure: the modernist architect/urban planner acting as a demiurge, fighting world authoritarian and vulgar perceptions. This archetype has its own history, dense and multiform, and came even to the cinema through The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand's novel, adaptation directed by King Vidor in 1949. Luca was your personal view of this archetypal figure? What about the development of such character? Now I have to confess that I’ve never read The Fountainhead, nor seen the film – I must try and do so! Luca first appeared as something of a background character (although a pivotal one) in The Defeat of Grief, and I never planned on him appearing again. But he did! I never attempted to train as an architect – I wouldn’t have stood a chance – but I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in buildings and their creators (this also includes structures and engineering such as bridges and tunnels). As a teenager I found books on modern architecture, and was captivated by the architects’ visions. It was even more inspiring because they were being built: Brasilia, for example. Of course, there have been all sorts of problems and unintended consequences – but I have to respect, if not love, the soaring visions. I imagine Luca to have come alive to a vision of the future when he was a very young man. However, he had the intellectual ability to make something of himself, and also the social and political skills to navigate his way through minefields of academia and patronage. I do not intend Luca to be a ‘good’ man – in fact at times he has been a total bastard! But he does what he does in order to survive and remain true to his vision. This comes at a cost to himself and to those close to him. The highest success is only one step back from ruin and defeat. Hopefully Luca will return at some point. That man is a born survivor – he learns from experience! And he’s a genius. But as a human being he’s flawed, and certainly damaged. Some stories seem to generate characters who must work in the background, who influence and fix events, who wield power over others, but remain behind the scenes and in the shadows. They are the people who have to do things for other people because the other people can’t be seen to be involved. On the level of fiction I like these sorts of characters, and the ‘secret history’ of their worlds. They are not ‘nice’ or ‘good’ people – but they are as they are for a reason, just as people who take risks, hurt others, and cause damage have often themselves been hurt and damaged, somehow. Well-adjusted and contented people don’t make very interesting characters. In your narratives, the architecture (as a style, a form, a concept) becomes a exquisite element, not only related to the concrete spaces but also to the sensuous perception and physics of cities and their buildings, crossing the skin and bones in characters like Dr. Cristian Luca, mentioned in the previous question. Incidentally, there is in the novel The Lustre of Time a memorable passage, in which Luca declares his desire to dissolve himself, merging his atoms with the walls around. Where you located the origin of this personal and unique architectural approaching used in your stories? As I said, I came across modern architecture in books. But there was also the country I was growing up in. It was being built, or was still new. I’m too young to remember Harold Wilson’s 1963 speech in which – according to the internet – he said ‘In all our plans for the future, we are re-defining and we are re-stating our Socialism in terms of the scientific revolution. But that revolution cannot become a reality unless we are prepared to make far-reaching changes in economic and social attitudes which permeate our whole system of society. The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry.’ But I grew up in a country in which to some extent Wilson’s vision did get the chance to be worked out. The future was going to be brighter, cleaner, safer. Slums were being demolished and new housing built. In some places the ruins caused by World War II were finally being swept away – in London there was the Barbican scheme and Route XI. Sleek motorways crossed the country. Jet airliners like vast metal birds flew overhead, and I watched the Apollo missions on TV. Now we know that new solutions give rise to new problems, but to this child it seemed that only challenge and wonder was in store. I read comics and watched films and programmes on television which showed the marvellous buildings and world of the future, and I thought that one day I should see them and live in that world. Sometimes I feel that the bright future has been stolen, so perhaps I try to compensate for that loss in some of my stories. I consider specially outstanding your short-story “Twilight of the Airships”, a narrative based in a singular speculative concept whose climax, the “invisible battle” between the Soviet and Nazi airships, brought to my mind both the novel also populated with airships The War in the Air, by H. G. Wells and also certain Jorge Luis Borges tales as “El milagro secreto”. Why this approach to the airships as the plot defining form, in this particular case? However, your approach to the airship technology, far from conventional steampunk views, would be closer to scientific novels of H. G. Wells, Charles Hinton or J. H. Rosny? My interest in airships comes from childhood. Like most boys I was interested in mechanics and machines – the bigger the better. I had a Meccano set and lots of Lego bricks. I was never much interested in cars or trains (even steam trains) but I loved ships, aircraft, and rockets. I used to know how the various types of engine worked, how to recognise the different jet airliners and World War II planes, all that sort of thing. Sometimes our father used to bring home books for us that he’d bought, and on one occasion he gave me a book about airships – from balloons to the World War I Zeppelins to the great airships of the 1930s and the era that ended with the Hindenburg disaster. There were lots of pictures. (I wish I had that book now, but I must’ve given it away or lost it.) The thought of these majestic craft the size of ocean liners plying the skies in commerce and exploration still fascinates me. I’ve loved Wells’ work since first reading The Time Machine when I was ten or so. I only read The War in the Air fifteen years or so ago, and I expect it was in the back of my mind when I wrote “Twilight of the Airships”. There were also the real-life accounts by the crews of the German Zeppelin bombers and the British fighter pilots trying to shoot them down. My grandmother saw a Zeppelin shot down in flames over north London, and she had a postcard showing the smashed metal framework on the ground. Another confession – I don’t know Borges’ story at all. Another situation I should remedy. I am really not at all well-read! I realized a recurring interest (even obsessive, maybe) through your stories on maps and in the definition of borders. The greatest example of this interest is the novel “The Unfolding Map”, included in the Infra Noir collection, centered on the strange mystique of the borders redesign and reconfiguration, an operation that jump from paper to reality. Such interest would derive from European history? Or is a kind of experiment with the power of idea contrasted with the restrictions of material/political reality? Yes, I think my interest in boundaries and their changeability comes from being interested in European history, although my interest in European history probably only started getting serious after I’d discovered the concept that countries’ borders were not as stable as I might’ve thought. When I was thirteen or so I was bored during a school holiday. There wasn’t much to do where I grew up. I went to the town’s library, and then into the reference library, and for some reason took a historical atlas from the shelf. I remember taking it over to a table and sitting down – and then being plunged into a world of shifting frontiers, with empires rising and falling in tides of different colours washing across the pages as I turned them. I must’ve realised that this charted the passing of decades and centuries. Names that had persisted through the centuries would suddenly vanish and be replaced by new ones. It all illustrated to me from an early age that nothing lasts for ever. And of course I quickly found out that the European frontiers I saw in my parents’ atlas at home were extremely recent. If borders have changed in the past, they could do so in the future – and many in Europe did eventually undergo thorough change in the early 1990s. And it all happened surprisingly peacefully except for the terrible, unnecessary, break-up of Yugoslavia. I suppose the power of idea lies behind many such changes: nationalism and the desire of a certain group and/or its leaders to enforce views of itself based along ethnic, cultural, religious lines, for example. Changes of border are one of the outward signs of something else – and that is what can be fascinating to make fiction out of. Times of war and economic turmoil have often been accompanied (or followed) by great creativity, and ordinary people showing what is best in humanity. Of course, creativity can also be stifled from above during such times, and people show the worst aspects of human nature. But I think treating these sorts of themes in fiction, and including real events and people from history can allow new insights to be born from the new stories. Or we can be reminded about things we ought not to forget. Behind border changes, behind the reality of changing the names of cities and streets, behind banning a book or smashing an artefact, there is also the reality of human cost, human loss, human pain. And yet there can still be humour, the bearing and sharing of burdens, the creativity. It seems to me that most people will always try to defy and overcome restrictions, however that might be in their different situations. Fiction can show that. The uncanny or weird effect in your narratives is quite subtle, with a hard philosophical investment. The strangeness in your stories is a gradual aspect, unveiled momentarily and covered again – an effect achieved by the clever use of continuity fragmentation and changes of views in the plot. Tell me about the process of creating this conceptual strangeness/uncanny/weird which I believe should not be enjoyed by certain fans of hardcore supernatural horror. I don’t think I’m aware of any conscious process – it just happens (or fails to happen)! I write very much by instinct, and quite often begin a story with no real idea of how it will end. I find that the process of writing a story tends to generate what then gets included, more so than any notes and outlines I might prepare first. What I do know is that I like subtlety rather than ‘blood and guts’ – although there is a place for that in supernatural horror fiction. Whether it’s always accurate or not, I prefer to think in terms of the ‘numinous’ rather than the ‘supernatural’ – although when it comes down to it I don’t really mind what labels get added! One of the essential aspects of your narratives – even before any editorial treatment – is the elaborated imagery, sometimes evolving for a visionary formulation. It would be extraordinary to see some of your stories, such as “Out to Sea” and “The Waltz of Masks”, in movies and on television. What is your connection with the aesthetics and cinematic thought? Do you have any future projects for cinema or television? I do tend to think in pictures, and I think that’s one of the reasons I often begin a story with uncertainty as to how it will end. Or sometimes it’s the end or climax of the story (not always the same thing!) that occurs to me first, and it occurs in visual terms. Then I make a note of it and then try to work out a story which can include it. “The Waltz of Masks” was inspired in part by the great set-piece ballroom and party scenes in one of my favourite films, Oberst Redl (directed by István Szabó). These are gorgeous and magnificent, feasts for the eyes (as well as the mind – as the entire film is). I don’t seem to watch as many films as I once did, but the ones I really like I’ve seen so many times and still watch again and again that I feel I know them well – although they can still throw up surprises, which I like! No, I don’t have any plans for cinema or television projects, and they’re not things I’ve ever considered doing myself. But I would certainly be open to anyone who wishes to adapt or collaborate… Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). Below, some works by John Howard: Written By Daylight, Secret Europe, Cities and Thrones and Powers, "Unfolding Map" (in the collection Infra Noir), The Lustre of Time. Jorge Luis Borges, in an extremely rich and suggestive essay entitled "Narrative Art and Magic" – compiled in the anthology Discusión (1932) – discusses the art of narrative was located close to the magic through the common procedures like analogies, unusual projections, the imaginative overcoming of the insoluble contradictions. A large arsenal employed for a simple goal: the transmutation of our usual reality and its strange causality in a new, complex reading. Damian Murphy, with his fiction, recovers this Borgean statements with new developments related to the games, the wandering, the initiation. In the novel The Salamander Angel (published in the collection Infra Noir), in the stories compilation A Distillate of Heresy and in his participation in the Fernando Pessoa homage, Dreams of Ourselves, Damian Murphy has set visionary relationships between magic and fiction.

In your narratives, there is a very evocative fusion between displacement (wandering) and mapping (the conquest) of real and imaginary territories, the transiting sphere for your characters. The transitions between real and imaginary topography are subtle and complex, so that your narratives get a enigmatic complexion, related to the initiation rites. An extraordinary example of this call to wandering arises in the story "The Book of Alabaster", in which exploratory and initiation wandering happens within a virtual video-game universe. What would it be the origin of your perception of wandering? How do you set this paradoxical relationship between the free travel and the need for a map? I’ve long been fascinated with the very human tendency to spatialize experience. Dreams, visionary experiences, initiations, video games, and narrative itself all demonstrate different ways in which we do this. Different cultural approaches to the mysteries use spatial metaphors such as the cube (along with other geometrical forms), the temple, and the city, to illustrate states, ideas, and relationships which are too abstract to represent directly. It seems natural to me to draw parallels between the abstract maps found in Kabbalistic works and esoteric Islam, for example, and representations of geographical constructs found in video games designed for older systems. To this day, I’m compelled by maps of old video game areas (you can find these all over the internet) in the same way that I’m compelled by depictions of New Jerusalem or the geography of Tartarus. The initiatory experience relies on the dichotomy between mapped experience and free travel, as you’ve termed it. On the one hand, a ceremonial initiation conveys the initiate along a route defined by symbolic values. Geometrical formations might be traced along a temple floor, for instance, with confrontations at various localities which represent the elemental forces of nature, or the stations of the sun and moon, or the phases of an alchemical operation. On the other hand, the initiatory process almost always involves an entry into unfamiliar territory, a period of searching for something of worth which is hidden, forcing the candidate to adapt to an environment in which they have no previous experience. Often, in my writing, I’ll begin with a particular structure which is concealed from the reader. The story will then be constructed as a sort of initiation of one or more characters into the mystery which is at the heart of that structure. In this way, the reader is made to wander through an environment for which there exists a map, but that map has largely been withheld from them. I put a lot of emphasis on intuition and sensation - the numinous speaks far better through these aspects of experience than it does through the purely rational. Maps of the intangible are something which I’ve always been attracted to. History is littered with maps of visionary worlds - from Dante to Blake to Swedenborg, the list is endless. Thinking back over the stories which I’ve written, every one of them seems to feature the cartography of the invisible in some way. Some more subtly than others. There are numerous references to buildings intended for ritual (or turn to do so, due to the action of various forces) in your stories. Some of this temples are described as physical buildings, other mapped by the mind or perceived in the same way as reality impossibilities by the rational mind of the characters (but not by intuition). In this sense, I believe that “Permutations of the Citadel", as well as the novel The Salamander Angel (published in Infra Noir collection), are great examples of your operations building this fictional structures for strange and unusual rites. How do you set up, in your narratives, these unique buildings? Is there any model – conceptual or concrete – for your, so to speak, fictional design of temples? With “Permutations of the Citadel” I was absolutely obsessive in my construction of the hotel in which the story takes place. On the one hand, this involves floorplans, maps, particular routes by which the characters get from one place to another, and things of that nature. But, perhaps more importantly, the spaces in which the rites and mysteries take place have to seem absolutely real to me. I try to invoke the richness of the experience of occupying an environment, to imbue the various spaces in the stories with a genius loci which, hopefully, the reader can relate to in a more or less tangible way. Without this element, I’d feel that I was somehow cheating. I do use models in my construction of these locales - a mixture of physical locations and photographs. It’s very easy for me to create a space and occupy it mentally, exploring all of the fine details, the textures, the scents, variations in lighting. In a sense, these buildings are as real to me as any physical space. My intention is to never use the same method more than once when it comes to creating buildings and structures which act as nexuses for forces, mysteries, and rituals. In the case of The Salamander Angel, the ruined church is shown on several subtle levels, demonstrating the adaptability of a particular place to myth, to the cycles of heavenly bodies, to the progression of archetypal offices of influence (among other things). In “A Perilous Ordeal”, the abandoned manor house plays a very different role, while the same is true of the hotel in “Permutations of the Citadel” and the penthouse in “The Scourge and the Sanctuary”. Each instance demonstrates a different way in which a building or structure can exist beyond its physical dimensions. Something that seems general to me in your stories: the exquisite taste for paradox, the confrontation between concepts that do not usually belong to the same sphere of conceptual meaning or even the same semantic nearness. This appreciation begins with the very title of several of your stories. In "The Book of Alabaster," the object of the title initially is not what it seems (though in the end, this first impression proves misleading). The dangers and the ordeal of the "The Perilous Ordeal" protagonist are not exactly those that the reader knows in the first pages of the story, with the interruption of an initiation ritual by Nazi soldiers. In this sense, your novel The Salamander Angel is a work in which the construction of the paradox manifests itself in a more elaborate way, from the angelic approach in title (almost an oxymoron) to the multifaceted plot construction. What would it be the origin of your complex work with the paradox? I don’t know that I’ve ever set out to specifically invoke paradox, though I think I’m so disposed to them naturally that I probably introduce those elements into my writing without necessarily intending to. There are definitely places where I’m interested in the resolution of two opposing ideas or archetypes - reference is made in The Salamander Angel, for instance, to a place in which the celestial can’t be distinguished from the infernal. There are often opposing elements which must be resolved in one way or another by the characters as well. I do tend to create spaces and artifacts which can’t quite be pinned down to one thing or another. The “book” in “A Book of Alabaster” is one example. As an object, it exists in several different contexts, making it quite difficult to define, and yet there is a particular idea or concept which underlies all of its different facets, though I may not choose to reveal exactly what that is. An exciting aspect of your narratives is a kind of update of the "cautionary tales" powers from the functional use (even in the Fairy Tales tradition), turned to an ironic game based on the contrast between what the characters look and what they find. An object (or idea) seemingly simple proves much more complex, as the games that conjure objects/buildings and its realities in "Permutations of the Citadel” or “The Scourge and the Sanctuary”. In this sense, you provide to the reader a whole poetics of permutation as some processes started by seemingly trivial mechanisms – games, casual and accidental discoveries, unexpected encounters – that become, through exchanges and meaning conversions, much wider and more challenging. This is a narrative creation path that brings to mind the "theory of correspondences" between the planes of existence by Emmanuel Swedenborg. What is the basis of this subtle and rich narrative game? A certain amount of this is autobiographical. I’ve always tended to engage with my environment according to strategies which might be termed arcane, and to pursue things that aren’t generally valued, or even considered, by the majority of society. There’s a tendency for the characters in my stories to treat the world as if it was a game, or a mystery to be explored, or even a lover to be courted. Often a character will seek something without entirely knowing what it is that they’re after, or they’ll interact with their environment according to a set of rules which completely disregards the assumptions generally made about the order and structure of the culture in which they live. I’ll often lead a character into a place in which they’re not supposed to be. There’s an archetypal element to transgressing or crossing a boundary. There are whole areas of experience which can be invoked and explored in this way. Often, by way of a sort of sympathetic magic, the crossing of a physical boundary will result in the breach of a much more tenuous threshold. I find myself continually coming back to this dynamic and finding new ways to explore it. I’m fascinated by the things that people do in the places where they work. There’s something so compelling about the possibilities which lie just beyond the arbitrary boundaries of what we’re supposed to be doing in a particular context. Messing around on the job can be elevated to an art form, or, as in “Permutations of the Citadel”, an initiatory path. In The Salamander Angel, there’s a section in which the character Nikolai stands on the roof of the building in which he works and observes another night worker through binoculars. He might be accused of violating another person’s privacy, but he just can’t resist observing, with intense interest, the rites and incantations by which another person carries out their professional tasks. Within the stories themselves, I’ve enjoyed playing games with the reader, often deliberately making use of deception and misdirection in order to conceal narrative, thematic and structural elements which might alter the interpretation of the piece. There are almost always hidden layers that might be discerned by paying close attention to particular aspects of the story. Again, I try to avoid using the same trick more than once, so if a key to one story is found, it generally won’t fit with any of the others. There’s an element of play in this approach which is very necessary to my creative process. On the other hand, I try to avoid creating something which can be reduced to an elaborate crossword puzzle. The sense of place and mystery, the emergence of the structures and themes which are at the heart of the story, and the flow of the narrative all have to get equal attention. Your short (but remarkable) novel The Salamander Angel features a unique structure of complexity interactions: multiple characters, performing different ritualistic activities, composing a process that only reveals itself in all its amplitude at the end, loading the intricate plot with a kind of metaphysical suspense. Tell something about the construction of The Salamander Angel – problems and solutions, essential ideas to the plot and other questions about this brief jewel of fantastic fiction. When I began the story, I had little more than the opening paragraph and the first traces of the Breaking and Entering chapter. Having no idea what direction I wanted to take things in, I compiled a list of themes I wanted to include, and the scaffolding upon which the narrative is built immediately revealed itself. The ritualistic structure of The Salamander Angel is based on a particular process which I’m hesitant to reveal too much about. It’s an initiatory process, the core dynamic of which is quite audacious and foreign from the point of view of exoteric religion, yet traces of it can be found all throughout the history of western esotericism and literature. The implications of this process are at once catastrophic and harmonizing, it involves an extreme change in the point of view of the person undergoing it. My hope is that the reader will be enabled to approach the hidden mechanisms of the story, however obliquely, in an organic way by engaging with the characters, settings, and plot. In the story, the initiatory process takes place in the context of a building, a city, and ultimately the world rather than that of an individual (though each character is affected by it in their own way). Only one of the ceremonial officers seems to have the whole picture, the rest play their parts with only a partial understanding, at best, of what’s going on. This approach made the story a very enjoyable one to write. The other main theme of The Salamander Angel is transgression. Shortly before beginning the story, I was asked to speak at a public event in anticipation of a dance performance. The performance involved the Watchers of the Book(s) of Enoch, the Nephilim, the fallen angels and other related topics. I don’t remember exactly, but I don’t think I had more than a day or two to prepare. I quickly put together some thoughts on the theme of transgression on a grand scale, tying the stories of the fallen angels and the Nephilim to our very human tendency to transgress our natural boundaries, contexts, and limitations. Once I’d hit upon the main structure of the story, I found that these ideas fit perfectly. The other motifs – the Salamander Angel, the lodestone, the star Algol – each play their role in bringing about the transformation which may or may not take place within the story (there’s nothing to suggest that anything really happens other than the delusions of an unconnected group of eccentrics). I have a notebook in which the entire structure is plainly laid out, with explanations of all of the different elements - I wanted to have something to ensure that I didn’t forget what I’d done! Both in the novel The Salamander Angel as in the tales of the collection The Distillate of Heresy there are times when the usual structure of the plot becomes a little more abstract, poetic maybe. I think, for example, in the chapters "The Rites of Bibliomancy" and "First Excerpt” of The Salamander Angel, in which you have dropped the narrative causality in favor of a different approach to the fictional universe, more symbolic and guided in the aforementioned aspect of correspondence between different spheres – or if you prefer, the permutation way. In this sense, you want to work in other genres such as poetry, in the near future? Is there any of your future project already defined? I do have some ideas for pieces which embrace the poetic side of things more than the narrative. I expect that those elements will continue to erupt unexpectedly within the flow of narration from time to time as well. As for future projects, a new novella should be published soon. I’ll keep the details concealed for now, other than to say that it involves several mysteries found within Catholic liturgy. Aside than that, a new batch of stories is in the works. I have enough ideas to keep me going for some time, and inspiration has been increasingly kind to me as I get older, so I imagine there should be quite a bit more to come. Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). NOTE: The first three beautiful photos below were kindly provided by Jonas Ploeger, Zagava Press editor, with the covers from, respectively, A Distillate of Heresy, Infra Noir and Dreams of Ourselves. In the film Andrei Rublev (1966) directed by Andrei Tarkovsky there is a curious scene, bizarre though valid and feasible from the point of view of a cinematographic work that was intended to be a historical reconstitution of the invisible, that is, the life of Andrei Rublev, the enigmatic Russian artist who lived in the fourteenth century, acclaimed as the most important and recognized icon painter in the History of Russia. When one character in the film, Kirill – another icon painter, extremely erudite and bookish – back to his monastery after years of wandering (recounted in episode 6, “Charity”), he realizes that a group of horsemen are being projected projected upside down on the wall opposite to the window which is closed by heavy shutters. Despite the barriers in the darkened room's window, there is space for the entrance of a tiny light beam, responsible for the marvelous and brief projection. A mediocre painter of icons, Kirill intuitively discovered the secret that afflicted the art from ancient Greece in this ad hoc camera obscura: the discovery of a method for capturing the movement of life, shaped in moving pictures. But that's not enough for Kirill to escape his own mediocrity – although inventive, he would never emulate/rival Andrei Rublev, a painter who did not need technical apparatus, narrow references in the tradition or prefabricated epiphanies. What Rublev did was paint a vision – the reality of the universe and the imagination – which only he had, something inaccessible to reproduction, even if a very sophisticated technique were employed. But humanity would pursue in devices and technological utopias the views articulated by Andrei Rublev (or Michelangelo, or William Blake, or Francisco de Goya, or Vincent Van Gogh, or Francis Bacon): cinema is perhaps the most stupendous result of this millennial effort that is both an attempt to capture the movement of life as a way to reproduce visions which we have access to only in the contemplation of great paintings or unique epiphanies.

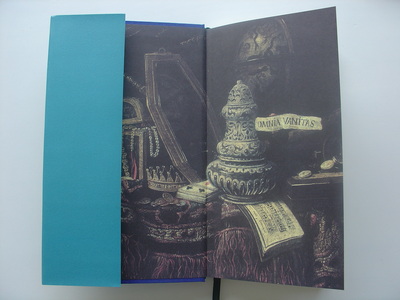

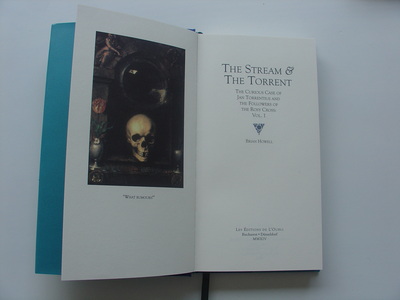

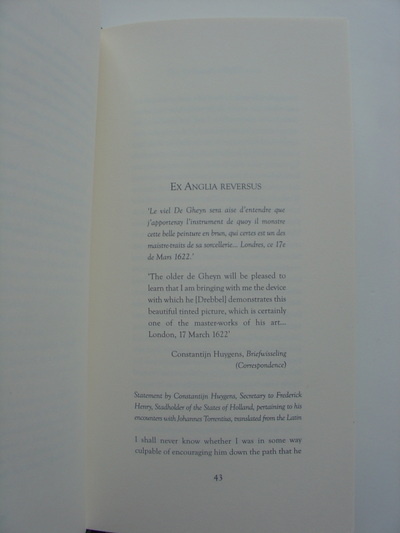

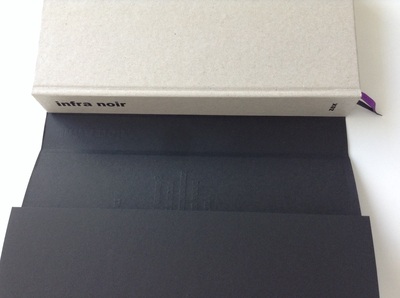

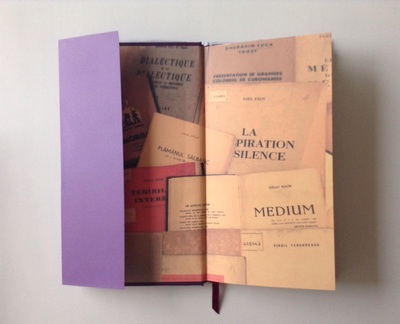

It is curious that this intuitive discovery in Tarkovsky's film, although entirely fictional, is still achievable. The history and origins of the camera obscura are large, mythical and erratic, appearing in ancient China and in the Aristotle's researches, in the medieval Arab Engineering treatises and in the experiments by Anthemius of Tralles, the mathematician who designed Hagia Sophia in the days when Istanbul was still called Constantinople. The Ancestral Skyline of History has some fixed points with conventional nomenclatures, so in the context of what we usually call “Antiquity" and the "Middle Ages” – general names for didactic purposes – the knowledge protruded from much more complicated paths that nowadays, with unifying processes, databases, instant media, systematical records or patents. The obscure details and possibilities of the past added to the desire to achieve what might be called absolute image – a paradox which brought together the perfect reproduction and the imaginative vision of complete beauty – is what fuels the extraordinary novel by Brian Howell, The Stream & The Torrent (subtitled The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius and the Followers of Rosy Cross: Vol. 1), released by Zagava/Ex Occidente Press collection Les Éditions de L'Oubli in 2014. It should be noted that Brian Howell is not a newcomer: he delved into the intricate and fascinating cultural universe of the seventeenth century (with a focus on Vermeer) in his first novel, The Dance of Geometry (2002). He also wrote a short stories collection on contemporary Japan, The Sound of White Ants (2004), recovering both Japan's tradition in his foreigner’s point of view in the style of Lafcadio Hearn and the works of Yukio Mishima. In The Stream & The Torrent, Howell returns to the world of artists, scientists, inventors, noblemen, conspirators and charlatans of the seventeenth century, but the focus is no longer a well-known painter. Johannes Torrentius (1589-1644) – who has adopted a Latinized and slightly modified version of his Christian name, Johannes van der Beeck Symonsz, in which “Beeck” means “brook” – was considered a master in Still Life already in his time, but this recognition did not prevent much of his works being burned due to accusations that the painter was a member of the Rosicrucian Order, an adherent of atheists and Satanist beliefs. The reputation of Torrentius preceded him: he was seen as “seducer of burghers, a deceiver of the people, a plague on the youth, a violator of women, a squanderer of his own and other’ money”. He stated that his works paints were “other", his paintings were the result of some kind of magic, that "it is not me who paints”. Eccentric and arrogant, he was arrested, tortured and condemned to the stake. He was saved by the king of England, Charles I, and became his protégé in 1630. For some time, Torrentius lived alone in England, at the expense of its powerful new boss. But in 1642, he had to leave his comfortable exile in London, perhaps due to the perception that the recently started English Civil War would lead his patron, fatally, to be beheaded. Torrentius returned to the Netherlands and was arrested again for some time; finally released, he went to his mother's home to die, some say due to a relentless syphilis infection. A February 7, 1644, he was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), a remarkable fact when considering the rumors about the deceased and his atheism, heresy, blasphemy and devil worship. His works have disappeared without a trace: part of them in the first imprisonment. Some works could have survived through the English exile; in fact, the inventory of Charles I mentions several paintings by Torrentius but none were found later. Only one of his works survived to be discovered in the twentieth century: Emblematic Still Life with Flagon, Glass, Jug and Bridle (1614), an extraordinary and complex allegory of moderation. The reflections' shadow-play in every surface of this painting – metal, glass, wood – seems to build a fiery and dark universe of fantasy through strange shadows and mysterious ways. This amazing painting, the only work by Torrentius that has come down to our time, it is one of the central devices in Howell's novel. The Stream & The Torrent is divided into three chapters: “Vandike and I”, “Ex Anglia Reversus” (poetically evocative and powerful expression, which was for some time the working title of the book) and “Cornelis Drubelsius Alcmariensis”. Each chapter presents a fragment of the mysterious life and work of Johannes Torrentius from a privileged witness’s point of view. In the first chapter, the very Johannes Torrentius, in a kind of diary, describes his exile in England and attempts to retrace his artificial and complicated processes to capture the life in images with blood, magic and a sort of art. In "Ex Anglia Reversus", the witness is Constantijn Huygens (father of the scientist Christiaan Huygens, inventor of a device which was the precursor to the cinema called the magic lantern, according to the historian Laurent Mannoni's researches in his book The Great Art Of Light And Shadow), the arbitrator in a strange duel of still lifes between Torrentius and the father and son De Gheyn. Finally, in the last chapter, the testimony of Cornelis Drebbel of Alkmaar, renowned for inventing the oven thermostat and for the construction of the first functional submarine; Drebbel reports his experiments alongside Jan Torrentius in London and Prague to the powerful final narrative hook. Historical characters intersecting each other in contexts not only credible but feasible: there are political games, palace intrigues, aesthetic discussions and bizarre/useless or cruel (depending on the point of view) inventions. This is a complex narrative texture, centered in fragmentary testimonies: the uncertainty of first-person narrative is multiplied by authors' distortions and manipulations, as well as the perception and reading of every fragment. The elaborate poetic construction made by dubious patches and a testimony that apparently can only be taken as true after a process of systematic collation – exactly what remains of Johannes Torrentius fascinating personality. Above all, the novel The Stream & The Torrent is a brilliant allegory of cinema, the human dream (achieved thanks to the technology) to capture life in all its detail, as through a dark process of black magic. In this sense, Brian Howell approaches Adolfo Bioy Casares novel The Invention of Morel, but exceeds the Argentine author to work not with pure fantasy invention of a machine that captures the substances and then plays this substance endlessly through a perpetuum mobile mechanism. Wonderful idea/image, but also conventional. Johannes Torrentius's “other paints” and camera obscura have an unstable concreteness provided by historical accounts, vague memories and dubious records; it is both a feasible (but unrecoverable) invention, a fraud, a hoax, a sleight of hand, a prodigy. The book, physically, follows the standard defined by the editors Dan Ghetu and Jonas Ploeger: it is an indisputably beautiful work of art. The printing is magnificent, on heavy paper with balanced typography, which reminds us of an updated version of the books that Torrentius and his friends manipulated in the seventeenth century. The internal images – curiously, none of them made by Torrentius – are beautiful still lifes of the seventeenth century, which guarantee to preserve a fully adequate air of mystery. We can only wish that the second volume is released soon, so let us enjoy the delicious, turbulent and atrocious Johannes Torrentius and his adventures in his quest for the absolute image while traversing the intricate conspiracies of this imaginary Rosicrucian Order. NOTE: Some of the historical references in the article above – especially about Johannes Torrentius – came from a series of articles (in three parts) quite enlightening by Maaike Dirkx entitled “The remarkable case of Johannes Torrentius” available at https://arthistoriesroom.wordpress.com/?s=Torrentius&submit=Search. The excellent review by Des Lewis, available on his website (https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/2014/10/24/the-stream-the-torrent/) is very useful and intriguing as well. n 1975, Jorge Luis Borges published a story that would materialize the dream of every bibliophile: "The Book of Sand", a book whose pages are infinite (or countless) as the grains of sand on a beach. The protagonist of the Borges tale acquires this fantastic volume of a Scottish Bible salesman who comes into his home but ends up a prisoner of that "monstrous", "diabolical" book. This is a impossible and fascinating object, – with a apocalyptic Rhys Hughes reading, in a tale of his New Universal History of Infamy – a symbol of what we desire and what feeds our worst nightmares, something that we can just drop in a place where the diabolical object will definitely miss, haunting us as a probable illusion of the senses. It is curious that the monstrous volume is not unusual: the cover showed that the book had passed through many users hands, the language in which it was written might be strange, but the typography was mediocre, the pages were worn, the illustrations were clumsy and mediocre. In a way, Borges was sensitive to a curious phenomenon – many everyday books, to a limited experience, reproduce the feel of the book of sand thanks to curious Nature dispositions. Time, for example, can waste a volume in a way that the once wonderful pages, come in our amazed fingers (that may not have touched these pages for a few years) as a brittle thing. In other way, the memory has the effect of astonishment at a book we imagine know (and that surprises us, which indicates that probably did not know for real) when certain passages that are in such and such page disappear, when new illustrations or directions emerge even in a brief, cursory reading. However, some book formats have always the tendency to emulate, of course imperfectly, the infinitude: almanachs and collections, that allowed the (re)discovery, the unexpected frisson in reading experience. But none of these methods of the Book of Sand, not a natural but perhaps a object of the possible realm (like many unnatural objects), is like this strange artifact published by Zagava/Ex Occidente Press: Infra-Noir, a multifaceted and unique compendium, the closest possible experience to the book of sand.