|

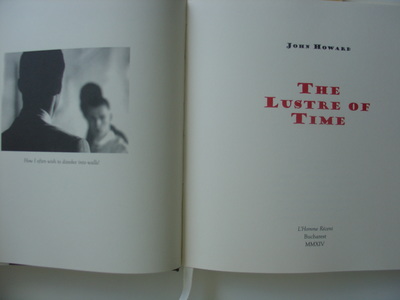

In a recent past, a very large History of the World seemed a good idea: authors like HG Wells sought audacious narrative synthesis of the multilayered historical process. The efforts were elegant or eventually reductionist in the task of extracting a logic in the History, a process that has certain essential disorder, as said Jean-Paul Sartre. In fact, a possible criticism about universal stories, perhaps the most striking critic, is precisely the approach of historical fact, because the universal historian appreciates the wonder facts and great names in a seemingly continuous line of progress. However, there is another History, populated by people and events unjustly ignored, remote or marginalized. This historical otherness, that is often not even known, emerges in a unique form in the works of John Howard. The marvelous fiction of Howard addresses fantastical phenomena and philosophical questions in the edges of our history and cognitive universe – sometimes in totally imaginary regions, as is the case of his most significant topographical creation, Steaua de Munte, a exhilarating region of imaginary Romania that can be visited in his latest novel, The Lustre of Time. Even the supernatural in Howard creations is subtle one, almost imperceptible – the uncertainty is the poetic weapon of John Howard in his antithesis of universal history, an imaginary history, unique and terrible.

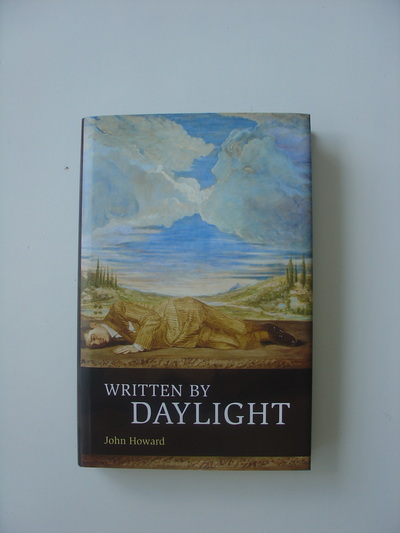

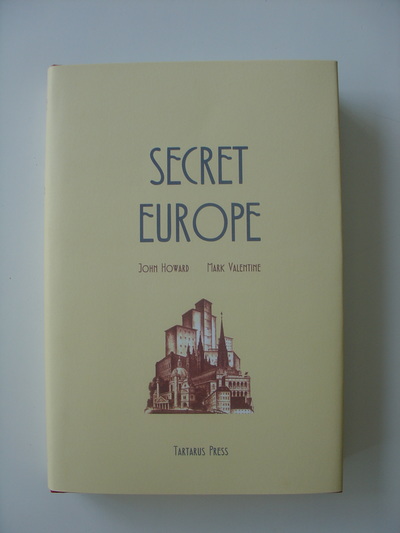

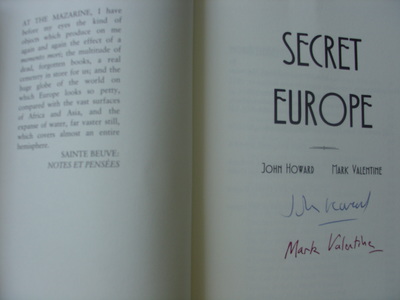

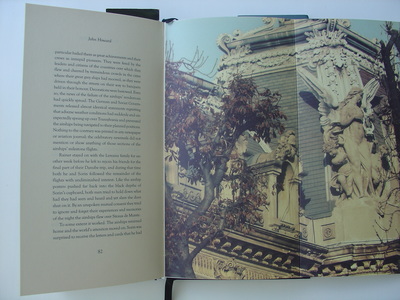

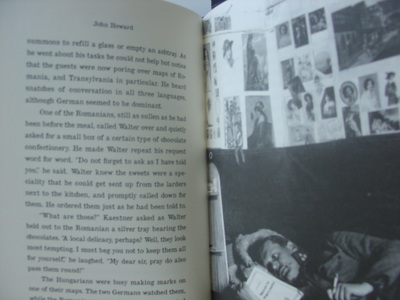

A very particular approach to urban topology, including the development of an entirely fictional town, Steaua de Munte, emerges in your works. This imaginary city is extraordinary, an entity that continuously develops itself over several short stories and novels, with its cafes, hotels, universities, hills, houses, buildings. It's an imaginary space equally or more extraordinary that William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County or Arkham by H. P. Lovecraft. So what would be the point of creating a fictional territory in such a distant place, covered in a peculiar picturesque mythology, Romania? What have been your sources and conceptual and imagery sources for the construction of Steaua de Munte? Modern Romanian history has interested me ever since I came across a contemporary account in John Gunther’s Inside Europe (1936, and subsequently much revised and reprinted). This was when I was still just a teenager and there seemed no reason for Communist rule behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ not to last for ever. I found Gunther’s portrait of the country as it had been nearly fifty years before my time to be utterly fascinating. Romanian politics were byzantine, Ruritanian, and murderous. And the country’s leaders – especially the flamboyant king, Carol II – seemed larger than life. John Gunther was an American newspaper reporter, a foreign correspondent in Europe for many years before and after World War II. He became one of those authors whose books I always look for. I have a shelf of them. I never forgot Gunther’s vivid and accurate summaries, and when Ceausescu and the other Communist leaders fell, it came as no great surprise to find their countries carrying on, in many ways, from where they had left off in the 1940s. There is so much in the histories of that part of Europe which seems almost operatic or something out of a television drama – if it had not been real, it could only be believed as fiction. But that is easy for an outsider such as me to say: these people were also responsible for ruining the lives of so many of their people. Fiction can examine the dark places – and should do. The opportunity to visit Romania came in 2009. The previous year Dan Ghetu’s Ex Occidente Press of Bucharest had published The Rite of Trebizond and Other Tales, a collection of stories mostly written in collaboration with Mark Valentine. Dan had read “The White Solander” – one of the tales of The Connoisseur that Mark and I had written together, and which had a Romanian background. Then Dan invited Mark and Jo Valentine and me to visit Romania. Dan and his wife were generous and painstaking hosts, driving us around much of the country in an exhilarating tour which nevertheless ended all too quickly and still left too many wonderful places unvisited. We crossed the mountains into Transylvania and stayed in the old cities of Sibiu and Sighisoara, and these were the main sources for my city of Steaua de Munte. But in most respects Steaua de Munte is a unique and special place, not dependent on anywhere else, and is what I, as sole proprietor, choose to make it – and remake it. Novels and series of stories set against a common background have always appealed to me, especially when the setting develops and changes, with various different aspects being revealed at various times, and yet which also leaves much to the reader’s imagination. Characters come and go (and families and relationships are vital) but the background scene, even when it changes, does provide a level of continuity against which new stories unfold and have consequences for the unwritten future. The protagonist of "The Fatal Vision" (the longest narrative of the book Cities and Thrones and Powers) and The Lustre of Time, Dr. Cristian Luca, embodies something of the archetypal figure: the modernist architect/urban planner acting as a demiurge, fighting world authoritarian and vulgar perceptions. This archetype has its own history, dense and multiform, and came even to the cinema through The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand's novel, adaptation directed by King Vidor in 1949. Luca was your personal view of this archetypal figure? What about the development of such character? Now I have to confess that I’ve never read The Fountainhead, nor seen the film – I must try and do so! Luca first appeared as something of a background character (although a pivotal one) in The Defeat of Grief, and I never planned on him appearing again. But he did! I never attempted to train as an architect – I wouldn’t have stood a chance – but I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in buildings and their creators (this also includes structures and engineering such as bridges and tunnels). As a teenager I found books on modern architecture, and was captivated by the architects’ visions. It was even more inspiring because they were being built: Brasilia, for example. Of course, there have been all sorts of problems and unintended consequences – but I have to respect, if not love, the soaring visions. I imagine Luca to have come alive to a vision of the future when he was a very young man. However, he had the intellectual ability to make something of himself, and also the social and political skills to navigate his way through minefields of academia and patronage. I do not intend Luca to be a ‘good’ man – in fact at times he has been a total bastard! But he does what he does in order to survive and remain true to his vision. This comes at a cost to himself and to those close to him. The highest success is only one step back from ruin and defeat. Hopefully Luca will return at some point. That man is a born survivor – he learns from experience! And he’s a genius. But as a human being he’s flawed, and certainly damaged. Some stories seem to generate characters who must work in the background, who influence and fix events, who wield power over others, but remain behind the scenes and in the shadows. They are the people who have to do things for other people because the other people can’t be seen to be involved. On the level of fiction I like these sorts of characters, and the ‘secret history’ of their worlds. They are not ‘nice’ or ‘good’ people – but they are as they are for a reason, just as people who take risks, hurt others, and cause damage have often themselves been hurt and damaged, somehow. Well-adjusted and contented people don’t make very interesting characters. In your narratives, the architecture (as a style, a form, a concept) becomes a exquisite element, not only related to the concrete spaces but also to the sensuous perception and physics of cities and their buildings, crossing the skin and bones in characters like Dr. Cristian Luca, mentioned in the previous question. Incidentally, there is in the novel The Lustre of Time a memorable passage, in which Luca declares his desire to dissolve himself, merging his atoms with the walls around. Where you located the origin of this personal and unique architectural approaching used in your stories? As I said, I came across modern architecture in books. But there was also the country I was growing up in. It was being built, or was still new. I’m too young to remember Harold Wilson’s 1963 speech in which – according to the internet – he said ‘In all our plans for the future, we are re-defining and we are re-stating our Socialism in terms of the scientific revolution. But that revolution cannot become a reality unless we are prepared to make far-reaching changes in economic and social attitudes which permeate our whole system of society. The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry.’ But I grew up in a country in which to some extent Wilson’s vision did get the chance to be worked out. The future was going to be brighter, cleaner, safer. Slums were being demolished and new housing built. In some places the ruins caused by World War II were finally being swept away – in London there was the Barbican scheme and Route XI. Sleek motorways crossed the country. Jet airliners like vast metal birds flew overhead, and I watched the Apollo missions on TV. Now we know that new solutions give rise to new problems, but to this child it seemed that only challenge and wonder was in store. I read comics and watched films and programmes on television which showed the marvellous buildings and world of the future, and I thought that one day I should see them and live in that world. Sometimes I feel that the bright future has been stolen, so perhaps I try to compensate for that loss in some of my stories. I consider specially outstanding your short-story “Twilight of the Airships”, a narrative based in a singular speculative concept whose climax, the “invisible battle” between the Soviet and Nazi airships, brought to my mind both the novel also populated with airships The War in the Air, by H. G. Wells and also certain Jorge Luis Borges tales as “El milagro secreto”. Why this approach to the airships as the plot defining form, in this particular case? However, your approach to the airship technology, far from conventional steampunk views, would be closer to scientific novels of H. G. Wells, Charles Hinton or J. H. Rosny? My interest in airships comes from childhood. Like most boys I was interested in mechanics and machines – the bigger the better. I had a Meccano set and lots of Lego bricks. I was never much interested in cars or trains (even steam trains) but I loved ships, aircraft, and rockets. I used to know how the various types of engine worked, how to recognise the different jet airliners and World War II planes, all that sort of thing. Sometimes our father used to bring home books for us that he’d bought, and on one occasion he gave me a book about airships – from balloons to the World War I Zeppelins to the great airships of the 1930s and the era that ended with the Hindenburg disaster. There were lots of pictures. (I wish I had that book now, but I must’ve given it away or lost it.) The thought of these majestic craft the size of ocean liners plying the skies in commerce and exploration still fascinates me. I’ve loved Wells’ work since first reading The Time Machine when I was ten or so. I only read The War in the Air fifteen years or so ago, and I expect it was in the back of my mind when I wrote “Twilight of the Airships”. There were also the real-life accounts by the crews of the German Zeppelin bombers and the British fighter pilots trying to shoot them down. My grandmother saw a Zeppelin shot down in flames over north London, and she had a postcard showing the smashed metal framework on the ground. Another confession – I don’t know Borges’ story at all. Another situation I should remedy. I am really not at all well-read! I realized a recurring interest (even obsessive, maybe) through your stories on maps and in the definition of borders. The greatest example of this interest is the novel “The Unfolding Map”, included in the Infra Noir collection, centered on the strange mystique of the borders redesign and reconfiguration, an operation that jump from paper to reality. Such interest would derive from European history? Or is a kind of experiment with the power of idea contrasted with the restrictions of material/political reality? Yes, I think my interest in boundaries and their changeability comes from being interested in European history, although my interest in European history probably only started getting serious after I’d discovered the concept that countries’ borders were not as stable as I might’ve thought. When I was thirteen or so I was bored during a school holiday. There wasn’t much to do where I grew up. I went to the town’s library, and then into the reference library, and for some reason took a historical atlas from the shelf. I remember taking it over to a table and sitting down – and then being plunged into a world of shifting frontiers, with empires rising and falling in tides of different colours washing across the pages as I turned them. I must’ve realised that this charted the passing of decades and centuries. Names that had persisted through the centuries would suddenly vanish and be replaced by new ones. It all illustrated to me from an early age that nothing lasts for ever. And of course I quickly found out that the European frontiers I saw in my parents’ atlas at home were extremely recent. If borders have changed in the past, they could do so in the future – and many in Europe did eventually undergo thorough change in the early 1990s. And it all happened surprisingly peacefully except for the terrible, unnecessary, break-up of Yugoslavia. I suppose the power of idea lies behind many such changes: nationalism and the desire of a certain group and/or its leaders to enforce views of itself based along ethnic, cultural, religious lines, for example. Changes of border are one of the outward signs of something else – and that is what can be fascinating to make fiction out of. Times of war and economic turmoil have often been accompanied (or followed) by great creativity, and ordinary people showing what is best in humanity. Of course, creativity can also be stifled from above during such times, and people show the worst aspects of human nature. But I think treating these sorts of themes in fiction, and including real events and people from history can allow new insights to be born from the new stories. Or we can be reminded about things we ought not to forget. Behind border changes, behind the reality of changing the names of cities and streets, behind banning a book or smashing an artefact, there is also the reality of human cost, human loss, human pain. And yet there can still be humour, the bearing and sharing of burdens, the creativity. It seems to me that most people will always try to defy and overcome restrictions, however that might be in their different situations. Fiction can show that. The uncanny or weird effect in your narratives is quite subtle, with a hard philosophical investment. The strangeness in your stories is a gradual aspect, unveiled momentarily and covered again – an effect achieved by the clever use of continuity fragmentation and changes of views in the plot. Tell me about the process of creating this conceptual strangeness/uncanny/weird which I believe should not be enjoyed by certain fans of hardcore supernatural horror. I don’t think I’m aware of any conscious process – it just happens (or fails to happen)! I write very much by instinct, and quite often begin a story with no real idea of how it will end. I find that the process of writing a story tends to generate what then gets included, more so than any notes and outlines I might prepare first. What I do know is that I like subtlety rather than ‘blood and guts’ – although there is a place for that in supernatural horror fiction. Whether it’s always accurate or not, I prefer to think in terms of the ‘numinous’ rather than the ‘supernatural’ – although when it comes down to it I don’t really mind what labels get added! One of the essential aspects of your narratives – even before any editorial treatment – is the elaborated imagery, sometimes evolving for a visionary formulation. It would be extraordinary to see some of your stories, such as “Out to Sea” and “The Waltz of Masks”, in movies and on television. What is your connection with the aesthetics and cinematic thought? Do you have any future projects for cinema or television? I do tend to think in pictures, and I think that’s one of the reasons I often begin a story with uncertainty as to how it will end. Or sometimes it’s the end or climax of the story (not always the same thing!) that occurs to me first, and it occurs in visual terms. Then I make a note of it and then try to work out a story which can include it. “The Waltz of Masks” was inspired in part by the great set-piece ballroom and party scenes in one of my favourite films, Oberst Redl (directed by István Szabó). These are gorgeous and magnificent, feasts for the eyes (as well as the mind – as the entire film is). I don’t seem to watch as many films as I once did, but the ones I really like I’ve seen so many times and still watch again and again that I feel I know them well – although they can still throw up surprises, which I like! No, I don’t have any plans for cinema or television projects, and they’re not things I’ve ever considered doing myself. But I would certainly be open to anyone who wishes to adapt or collaborate… Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). Below, some works by John Howard: Written By Daylight, Secret Europe, Cities and Thrones and Powers, "Unfolding Map" (in the collection Infra Noir), The Lustre of Time.

1 Comment

1/17/2023 10:52:07 pm

Wonderful information! We love to create powerful websites & apps for both mobile and desktop. We develop all digital platforms with SEO and Marketing Automation. Make your websites and apps stand out with incredible UX and UI.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed