|

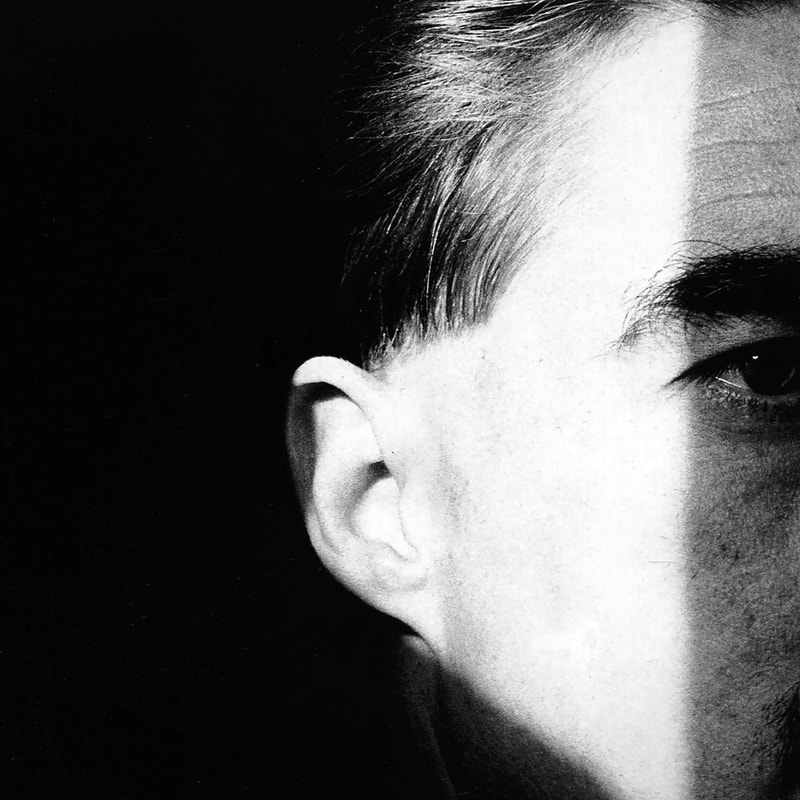

The old adage of Ecclesiastes (1:9), “nihil novi sub sole” – “there is nothing new under the sun” – seems to materialize in general a kind of rule, a ruthless, established and inflexible as steel rule. But the fact is that innovation, the novum need not arise from a brutal change, a revolution in absolute, total terms. There are amazing possibilities that arise from small nuances, handled with dexterity, skill, sensitivity. When faced with this kind of innovation, in a novel, poem or film, it’s possible to feel this kind of shine aroused by the masterpieces – something that someone can feel as soon as contemplate this cinematic "FIN", which closes John Howard's newest book, Visit of a Ghost. The novum of this brief (just over 35 pages) narrative by John Howard first comes from two aspects directly related to the plot. The first of them, already a well-known feature of those who accompany this extraordinary author, is the location: the imaginary city of Steaua de Munte. It is a triumph of Howard's imagination, obtained through the economic arrangement of seemingly trivial elements. The imaginary map of fiction is immense, diversified, from the legends of Prester John to Jonathan Swift, from William Faulkner to Gabriel Garcia Marquez. But Steaua de Munte is a strangely familiar landscape built patiently, its minimal elements (postcards, stamps, shops, coins) in conjunction with much larger ones (a world in which airships dominate all the aircraft industry), giving to the totality a fantastic figuration, almost of alternative reality. In this sense, John Howard seems to have in mind an excerpt from the poem "Juan López and John Ward", by Jorge Luis Borges (in the translation by James Halford): “The planet had been partitioned into different countries, each armed with loyalties, cherished memories, and an unquestionably heroic past; with laws, grievances, and their own peculiar mythologies; with bronze busts of great men, anniversaries, demagogues, and symbols. This division, the labor of cartographers, was good for starting wars.” The second aspect, in this sense, appears immediately in the title: a quaint idea of ghost. It is a fantastic element so employed in so many differentiated forms of narrative that its existence becomes almost derisory – the reader, in front of this word, initiates the mental process of accommodation of this concept in some of the innumerable possibilities already known and shared in the immense emporium of meanings available, recognized, cataloged. Here the two ghosts unfolds themselves, embracing aspects of it’s most simple aspects, however far from some innocent plainness. The encounter of these ghosts, two of them, is retained in much of the plot as a potential event, something that brings about an extraordinary quid pro quo whose complexity arises from an escalation of multiple incomprehension, something constructed in a simple but natural way, as many other everyday misconceptions. When these two ghosts finally converge, in a particularly extraordinary occurrence, such a climactic encounter reveals what may be the critical point of the narrative, in thematic terms: the discovery of another Europe, perhaps unfeasible nowadays, more open to the glance and presence of the Otherness. In that sense, John Howard's story brought to mind an essay by Ezra Pound titled "The Passport Nuissance," published in The Nation on November 30, 1927. In this brief essay, Pound vituperates against the formation of a new bureaucracy which, after World War I, made the disinterested activity of traveling more and more complicated. In that same spirit, one of the characters states (and this is the couplet that appears on the back of the dustcover): *My new book will be called Around Europe*. It is another Europe, potentially welcoming although surrounded by the usual tempestuous clouds of war, intolerance. But, perhaps, this is only a feasible meaning, a reading of many available. Physically, the book is extraordinary, magnificent achievement of the publisher Ex Occidente / Mount Abraxas. The balanced typography, the choice of photography as a significant element, even the use of this unexpected cinematographic resource, the "FIN" at the end of the book – it is a set of elements that follows the narrative in a subtle but indelible way. In fact, the use of photographic medium, allied with intelligent layout formatting, established unique, cinematographic effects. For, in fact, it is a story that could be on the screen of the cinema, specially a screen in the past, perhaps a puzzling film on the hazards of the nations like The Barefoot Contessa, The Last Command, or Mr. Arkadin.

0 Comments

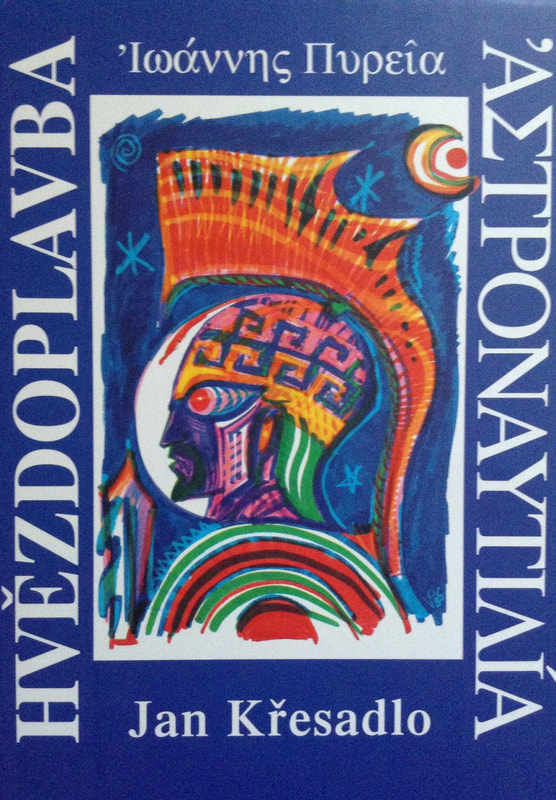

Some books have a special impact from their very existence, their being in the world; by not having a standardized presentation, a conventional exterior structure, become objects of fascination even before they are opened. Some present a strange, shocking or extraordinary cover illustration, this image being its source of magnetism more evident and concrete. Thus, the French translation by François Rivière of the J. G. Ballard’s novel The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), entitled La Foire aux Atrocités, published in 1976 by Editions Champ Libre – for the collection Chute Libre (“free fall”) – presents one of these extraordinarily picture with some striking layers. It is a kind of portrait, in the form of an illustration whose authorship is unknown, in which we have a face (female, probably) obliterated by blindfold and gag. The colors of the image (deep red, green, light brown, black that creates violent contrasts) are powerfully evocative, though the image itself has little to do with the content of the book, rounding the sex, yes, but not that way. Another more complex way for a book to express its potency in itself is by its volume, the way its outward structure is presented to the reader – in this sense, the recent collections Booklore and The Whore is This Temple are magnificent in a peculiar way. The first one, evoking the multiplicity of a library by its conflict between format and content; the second, because it is a kind of impossible object, a contemporary grimoire for personal rituals although it is not that, in fact, but a collection of narratives and poetic creations. Astronautilia is close to these two trends, but in a very unique way, because their impact happens in successive waves, that plays with expectations of the reader from one seemingly surpassed fright to another, culminating in a very own final decisive impact. In its dust cover, with a strong blue tone, a suggestive illustration by Václav Pazourek, the first image of the book and its real gateway: a portrait, in profile, quite colorful (the style suggests a vaguely primitivist expressionism) of what appears to be a warrior of the past, probably a hoplite of Ancient Greece. It is possible to identify in the image the shield, the helmet, the spear that this soldier holds. But the illustration, however, escapes this determination of meaning by a trait of technological futurism that runs through it – the white space between the face and the background of the image suggest an astronaut's helmet, adapted for use in sidereal space; the elaborate arabesques in the helmet suggest a civilization and a history that are not entirely human; the eye of the hoplite, at last, with a stylizedly almondlike shape and multiplied (by lenses? Or it’s an alien eye, in fact?) by the subtle effects used by the illustrator, a secure support for the odd strangeness. This extraordinary image covers and contrasts with the hard cover, much more austere – gently marbled dark blue, with the Greek part of the title engraved in silvery tones while the Czech part is in low relief – which refers to collections such as translations of classical and bilingual (Greek and Latin, of course) works published by publishers such as Éditions Les Belles Lettres. But the impact of the dust cover rich imagery, the fastness of the cover, and even the volume of this reasonably thick book constitute the first moment, preparing for the still greater impact with what we might call the linguistic discovery of its contents. For in the very first pages the reader is threw in a confusio linguarum of considerable proportions: there are texts in English, Latin, Czech – but all this is only the preparation to the poem, thousands of hexameters in glorious Homeric Greek handwritten. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed