|

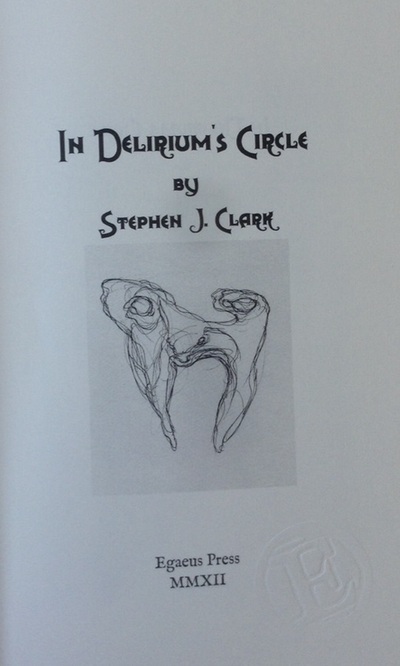

In his website, the “About” section has the following information: “Stephen J. Clark has been active within the International Surrealist Movement for over fifteen years, appearing in numerous surrealist publications and has most recently participated in exhibitions with the Czech and Slovak Group. (...) Returning to writing fiction in 2008, Clark's story ‘The House of Sleep' was published by Ex Occidente Press in the Gustav Meyrink homage anthology Cinnabar's Gnosis. Work has since appeared in various publications by Side Real Press, Supernatural Tales, Fulgur Limited, Talking Pen Press and Skrev Press among others. (...) The author's debut novel In Delirium's Circle was published by Egaeus Press in 2012. He is currently working on a collection of short stories.” (saw at http://www.thesinginggarden.co.uk/about.html).

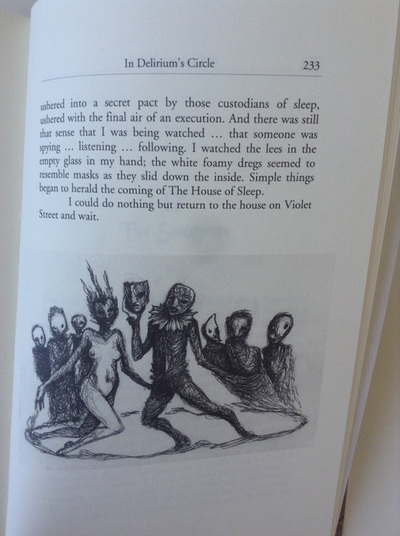

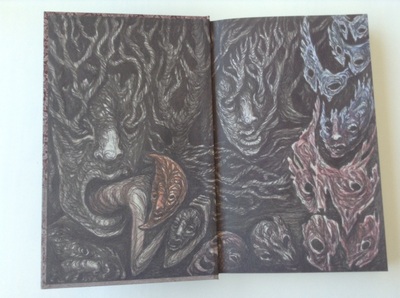

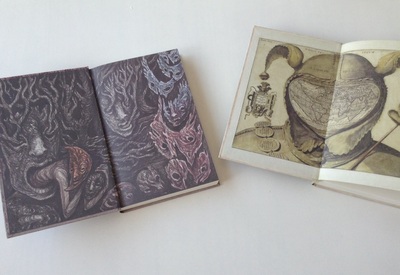

In your last book, In Delirium's Circle, a complex and discontinuous flow and relationship between Image (there are the illustrations but also many descriptions: photos, objects, places, etc.) and Plot. Are there any planning or method in this disposition or the automatism used by the characters influenced the narrative structure? And, in this sense, are there any past experience (in Narrative form) that influenced your vision here? With my writing I try to develop a dynamic between planning and spontaneity. I approach it as a form of play; a game allowing space for the subconscious to speak. Rather than seeing the subconscious only as a reservoir of suppressed images I view it almost as an active, volatile agent too that transforms what it comes into contact with. It lies in wait, latent or dormant in our relationship with the world as we experience it. It is not just situated deep within us but deep outside us too. I try to keep the story as open as possible to suggestion and change right into its later stages. Stories and images I think can have a life of their own and their development can be compared to alchemical distillation. My aim is focused on developing an approach to writing and storytelling as a hermetic method for myself, so the exploration of drawing in relation to writing is part of this experiment. I’m wary of anything described as ‘experimental’ these days, yet by experimental I simply mean play; creativity that includes chance and accident and openness to interpretation. I’m cautious too about describing what I do as having anything to do with occultism, in the sense that I don’t think one has to be steeped or versed in specialised or dogmatic knowledge to do what I do, or gain insight through such methods. For me commitment to one’s own imaginative creativity and intuitive understanding of experience and the subconscious can be a form of initiation and exploration in itself. I think there’s a danger in identifying with something in a dogmatic and formulaic way that closes down the free play of critical interpretation and creative experience, I think that can be just as true of surrealism as it is with magical traditions. I’m thinking of writers such Gustav Meyrink and Alfred Jarry, writers who I appreciate and admire for their knowledge and experience in hermetic ideas and practices, yet also for the wit and inventiveness of their individual approaches. The same can be said of Austin Osman Spare as an artist I think, for example in the way that he incorporated his experiences of cinema into his work in the form of his ‘sidereal’ methods. There’s a sense of invention and irreverence in all their work that keeps it volatile and alive to this day. I’m interested in the experience of imagining: for example the psychological and symbolic significance that the emergence and development of narrative events and characters could have for the writer’s inner life. I see the process of writing a story as a form of personal exploration, an act of gnosis, of self-knowledge. The story is a microcosm, a theatre where the inner life’s dramas are played out. I’m inspired more by ideas from hermetic philosophy than literary theory. A great many if not all academic observations about narrative theory can be recognised and contemplated intuitively anyway, without the need to identify them with specialist literary terminology. What matters is the individual’s experience of these forms. Somewhere within my method there are ideas concerning the use of what could be thought of as “discontinuous” forms, alternating between prose and visual image, to cause subconscious ruptures in the linear, discursive flow of words and suggest that another way of engaging with the narrative must be sought by the reader, yet I have to say that I don’t allow myself to scrutinise and dissect that too closely in the process of developing the story. I think to focus too much on that would divest the story of its rawness and frayed edges. I think it’s vital to my creativity to be attentive to what might arise from the subconscious; mapping and developing a story from the primal matter of the subconscious yet refining it, distilling it through methods of interpretation and imagination. I think writing can be compared to a waking dream where the writer and the reader alike are enticed as if by seduction, as if under the influence of an enchantment, seduced by the incantation of words into dreaming together. I see the story as being the residue of a dream; dream and the waking world meeting in the form of words and creating an artefact. To paraphrase Jacques Lacan; the Unconscious is structured like a language. I think my experience of structure in my writing at least in part emerges from a kind of meditative dream, following another kind of logic; a logic close to dreaming. I don’t simply mean that a story only emerges from a method like automatic writing. Images and ideas arise from the subconscious as if they’d offered themselves seductively, returning to your thoughts to show you another facet. My process is more to do with interpreting and exploring these images and ideas imaginatively to see where analogical thinking might take me. The visual images rupture the flow of words. There are many phantoms in the novel. The visual images haunt the prose, they intervene rather than illustrate; they interfere with what’s being said. And they suggest that another approach must be found because another kind of understanding is required. As dreams have their own logic and momentum so too do stories, at least the kind of writing I’m mainly interested in. Writing and reading can act as a bridge, a space where dreaming enters waking life. I see what I do as tapping into a rich source or stratum of language, imagery and culture that one could call mythology. I believe Apollinaire and Andre Breton said of De Chirico’s paintings, that they represented or embodied a kind of modern mythology; charting the undercurrents, the nightmares and the enigmas of his own time. In terms of past experience of narrative structure, if I understand you correctly you are talking about ‘literary influences’. I think there are writers that I’d previously read that must have formally influenced how I write, such as William Faulkner, whom I single out especially because of the obvious characteristics of form he used in many of his books, yet I must emphasise that it is the experience of writing as a form of meditative play and dreaming that drives me; writing as personal revelation. Much of the structure can be found as I write and respond to accommodate and explore what arises. I don’t think it would help to list writers that I appreciate here. I used to have certain favourite writers but currently I can’t say that I do. The structure I find effective reflects how I understand experience; the interplay of multiple perspectives and the elliptical, discontinuous nature and enigmas of communication, the enigmas of intimacy, the intimacy too between the reader and the story they engage with. I prefer such a structure as I feel it reflects the hidden polysemous nature of reality and experience. I know that runs the risk of sounding grandiose but ultimately it comes down to empathy. I’m not interested in writing or reading something purely as a piece of entertainment. When the old cliché “Write about what you know” is wheeled out I’d have to say that there are many ways of knowing what’s there in front of you, there are many ways of imagining the real other than so-called realist representations. “Write about what you know”? What do I know today? I know that my day began with a dream. In your novellas (narratives more lengthy in extension, in this case), The Satyr and In Delirium's Circle, there are some kind of tendency related to the narrative disintegration: from a more or less stabilized starting point to a more subjective and abstract universe, commanded by some visionary State. Is this a influence of the powerful Image and Vision (including illustrations and design with a high and unique meaning in the both of books) in this novellas? Or it's a poetical direction assumed to the plot? I see it as a matter of transformation which involves the disintegration of what went before, the disintegration of the habitual; the disintegration and dissolving of the conscious in the subconscious perhaps. The stable is made volatile and vice versa. The world is turned on its head. Out of the chaos of madness another form of understanding arises. I think of the old maxim from alchemy, no generation without corruption, or in other words: new forms arise out of decay and destruction. As I’ve mentioned earlier, I do express a personal “worldview” or philosophy in my stories, so to speak, not in any didactic way but simply because I’m passionate about exploring those ideas for myself to see where they will take me. I think it’s inseparable from how I write. It informs the language and form of what I do. It informs the tone and atmosphere of what and how I write and draw. I prefer writers and artists who do have a “vision” of their own that can be explored over time. I find that a rewarding and enriching experience and I think it relates back to the idea of mythology, the development of a writer’s personal symbolism over time, the way an individual engages with the world through their imagination, through their subconscious mind as if they are consulting an oracle and acquiring insight. There are some claims, for one side to another, about the powers of suggestion in Literature and the Visual Arts: sometimes one side is on top of another and vice-versa. It's not impossible to saw that your narrative work follow a borderline between these two fields. So, for you, the suggestiveness in Literature and Visual Arts follows a equal pathway or it is not the case and one outdo the other. Is it possible a medium resolution? Rather than involving an aesthetic or theoretical opposition between Literature and the Visual Arts I see it more in experiential terms; in the sense of how one experiences visual images and words, how they attract and repel each other. Especially with In Delirium’s Circle, I am playing more with those ideas and attempting to explore the elliptical nature and enigmas of how we experience images and words, of how we communicate and how we understand our senses, memory, community and history. The fabric of the perceivable world and the world of human exchanges consists of experiential, sensory, epistemological and existential uncertainties. Everyday life is made of numerous flaws and fissures in our understanding, of strange inexplicable moments and chance events that we learn to repress and forget. Often what we consider a social or even scientific certainty will be at least in part a construction of habitual consensus. So I’m trying to convey these ideas through the structure, for example in the way I use the epistolary form with In Delirium’s Circle. I felt that form was effective as it allowed me to play with the ambiguities of identity and communication; to accentuate the absences and silences and mysteries of human life that are commonly disregarded. I like to take common experiences, something like mistaken recognition, of thinking you know someone when you don’t, and playing with the mysteries of that enigma. I’m interested in what I’d call enigmas of intimacy. I think the experience of reading and writing is an area rich with such enigmas of intimacy. I’m thinking of the term intimacy as Georges Bataille might define it, as involving risk and vulnerability. Of course that dynamic is charged with inherent longing and promise, the longing for empathy and transference … the dissolving of individual identity in words and silence. It involves the significance and ambiguities of silence - of using form and language in such a way as to express something that is beyond words, or that slips between words. It involves the use of language and silence, or image and absence to evoke something that’s Other, to summon something from the subconscious. I think my use of the interplay of words and visual images in this way is an attempt to reach this intimacy. With In Delirium’s Circle I’m engaging with ideas about what role mythology has in society, what power it had in that post-war era, partly in the form of propaganda, but in other ways too, and what power it still has and how mythology is used to coerce and influence others - mythology as an inner war. Yet also the reclaiming of mythology as an intimate thing, how it can be claimed back and explored subjectively and inter-subjectively by individuals. So I’m not interested in the current status of Art or Literature in aesthetic or theoretical terms, nor feel the need to comment on that status critically. Nor am I experimenting with form in that context. I don’t think what I do is anything new or different from what has gone before, or is an attempt at a resolution or middle way between Art and Literature as your question seems to infer. I just know I have to be as true to the story as I imagine it and true to my own imagination. I just think you have to be true to yourself and follow that obsessively. I like to think of In Delirium’s Circle as a fugitive artefact, an anthropologist’s field report, or a grimoire from a dream. The decision to include drawings in the fabric of the story wasn’t something that I approached as an experiment with form. The desire to explore that dynamic came out of ideas for the story itself. In the novel In Delirium's Circle, there are a kind of sect that is, at same time, a avant-gardist group, art community and even more, as the plot develops its layers. That's an amazing creation, so fascinating to the protagonist as to reader. What about the sources for the creation of this group? Are there some model in the distant or close reality? My understanding of surrealist groups both historical and current definitely partly informed the idea of The Circle in my novel In Delirium’s Circle. Yet I didn’t want to make it specific. I used that idea and those experiences to serve another aim, to convey the mythology of a secret community of outsiders and the mysteries of communication, the ambiguities of desire and sanity, the otherness of other people. I also wanted to draw upon associations of other groups too, not only intellectual and radical groups of recent history but also the myths of hidden or fabricated or lost groups such as the Rosicrucians and other hermetic fraternities that I’ve been interested in reading about for quite some time now, in the historical studies by Frances Yates for instance. Yet I suppose, in keeping with our own times, there are intimations of other kinds of groups, such as terrorist cells, again raising questions regarding the nature of belief and desire. The important thing for me was to leave it open, to use ambiguity to suggest the other world of this hidden community, that was very real and very human, with its own enigmatic past, existing within the world we think we know and yet involving a perception of life that’s very different from the wider consensus, that involves a way of life that’s at odds with the world of the wider society, a group of misfits brought together in their search for lost intimacy. Again, the idea of the secret group lends itself readily to the other themes of empathy, community, mythology and power. I’ve been interested for some time in the writings of Georges Bataille and the group known as Acéphale that he played a key part in forming. It was a group formed with the purpose of exploring what it would mean to be part of a secret community in relation to understanding wider society and exploring the nature of intimacy and communication. I’m aware of how that can be misunderstood as being elitist yet I think Bataille saw it as a necessary tool with which to truly explore experiences that would otherwise remain in the realms of intellectual speculation for him. Not only is it a way of demarcating a zone of exploration it’s also an act of resistance against the values of wider established society. The Circle in my novel is a microcosm of the thematic currents within In Delirium’s Circle. In a way it’s the hub from which everything else radiates or the pool into which everything else is pulled and descends and vanishes. Of course there’s a whole tradition within gothic literature and cinema of people having doomed dealings with hidden orders, cults, secret agents, master criminals and so forth and it’s something I’ve often enjoyed in literature, TV drama and film, so I’m also playing with that idea. I’m playing with those threads of association that already exist for me, not that it’s obvious or necessary for the reader to recognise them, yet in cinematic terms I’m inspired by the imagery say of Fantomas, or Georges Franju’s films Judex and Les Yeux Sans Visage, or Bunuel’s The Phantom of Liberty, or Svankmajer’s Faust and Conspirators of Pleasure. It’s an affinity I have with the currents that run through such work, which leads me to the next que Your novella The Satyr had some curious aspects related to the 1940s film universe. The name of one of the protagonists for start, but even the structure: some events in the novella brought me to the memory films like Fritz Lang's Ministry of Fear (1944), specially the chapter dedicated to the séance. Even Hitchcock's 39 Steps (1935), with the ambiguous feminine persona. Could you tell more about these cinema transnarrative and influences in these novella? Cinema is so part of the mythology of modern society. People have worshipped at the altars of actors for decades and still do. I don’t consciously allude to specific Forties films or use them to structure narrative yet I do attempt to evoke the noir atmosphere, particularly with In Delirium’s Circle. While working on my novel I would read and watch anything that I thought might inspire me, anything that might by some process of osmosis inform the atmosphere and spirit of the work, so I explored Patrick Hamilton’s novels and read Graham Greene’s The Ministry of Fear and The Third Man, although I watched the films after I’d read the texts. I’d never seen The Third Man film before that point, although I’d read the novella. And I only watched the film after I’d finished my novel. I wanted to approach it in the field of written prose you see. I didn’t want there to be any obvious allusions to or influences from having watched the film. There are other sources too that haunt the fringes of In Delirium’s Circle, such as the Quatermass screenplays and early adaptations. There’s something about the paranoiac atmosphere of those films, of there being an invasion from within that fascinates me. I think that’s a myth of that era, the myth of invasion, of some unnameable and nebulous threat arising from the commonplace. I wanted to evoke that myth in my novel. There was a film too that I watched just as I was finishing the final draft of my novel, it’s called The Clouded Yellow (1950). A noir thriller with moments that verge on the dreamlike and a chase sequence filmed in Newcastle upon Tyne, so watching it was an experience of synchronicity. I hadn’t known it existed until that point. Actually I find the experience of watching many of these noir films dreamlike, surely seeing the past in this way must be considered a kind of waking dream. So films and old TV dramas are an important part of my creative life and do inform my writing and my visual art. I’ve strayed from your question there. The Satyr was my way of engaging with Austin Osman Spare’s myth with an emphasis on him being a vulnerable human being rather than a legendary artist and magician. I didn’t explore his ideas in depth in the novella partly because of the emphasis I wanted to give. I think he’s a remarkable artist partly because he was a humble and vulnerable human being and not some god or genius as many believe - at least that’s my view. What keeps me interested in Spare are the anecdotes about his daily life and the encounters he had with the community he was part of. The imagery of The Satyr undoubtedly draws upon the cinema you refer to in your question yet more in terms of atmosphere. There is an element of noir mythology in the novella. Much of it works in terms of poetic suggestion. For example the use of a name such as Marlene Dietrich, can act as a kind of depth charge and has reverberations evoking all manner of nebulous and perhaps conflicting associations from that era. I used that name to suggest certain tensions in the story. The Satyr is my first attempt in print to explore the possibilities of combining prose with visual art, where the art isn’t simply a secondary illustrative thing but serves a narrative purpose too and actively contributes to the story, however elliptically. I’d worked on something similar before but with poetry. The poetry collection The Bridge of Shadows a collaboration with my old friend Bill Howe, explores a similar area where Bill’s photographs and my poems exist in a field of analogical and enigmatic associations. The photographs aren’t there as illustrations, they are a visual counterpart to the poems. So the image can act as a counterpoint to the text and vice versa. The title of the book infers this relationship. The image and the text exist in a complex relationship where they might on the one hand attract and on the other repel one another. The visual image might first seem to overpower and silence the poem or the poem might in some subtle way suffuse or question the image. And all the while in the flux of this dynamic interrelationship all manner of other poetic associations might be vying to be heard or imagined. The text and the image might cancel each other out or they might help each other to speak in another unexpected way. It’s a game that emphasises the part played by the reader to find their own associations between poem and photograph. There were too many external factors and pressures involved in the creation of The Satyr for it to fulfil its potential. It was completed within one month due to the deadline, so it was rushed. It was an opportunity I had to take at that time. As a friend remarked, it was like a concentrated version of a much bigger book waiting to emerge, which I think is a fair point. So I see it as flawed but I’m glad I did it. I’d like to revisit The Satyr but we’ll see. The form of combining image with text however may be rather unattractive to many publishers. In your work with book illustration – a special and unique work, a imagerie that dialogue with the plot and meaning of the book but preserve your marks and vision – the image creation process needs some narrative treatment, some form to create a visual and synthetical adaptation? When creating narratives that mix text and image, which one comes first? Tell us a little of his working method. I’ll answer these questions together if I may, as I think they cover similar ground if I understand them correctly. So far it’s depended upon the individual book. With In Delirium’s Circle the text came first in the sense that it started out as an unpublished short story. So that kernel of words came first yet as the novel took shape the drawings emerged as part of the momentum of creation. Part of it involved practical and budgetary considerations later, so discussions took place with the editor, Mark Beech at Egaeus Press, but if anything Mark encouraged me and said it wasn’t a problem to include more drawings and just take the time to get it right, to complete it as I’d fully envisaged it. So a few of the drawings came later in the process and were suggested to me from the numerous times I’d reread and redrafted passages of the novel. The Bestiary of Communion differed and is largely a conventional case of illustration. Two of drawings came after the stories were completed. As with The Satyr it was another case where publishing constraints meant a project couldn’t reach its full fruition and the result I think shows that it was quite rushed, at least with the story My Mistress, the Multitude. However with this story the image of the Countess/ Sphinx was developed as a drawing during the process of writing the story. With the writing of The Satyr it was a matter of sometimes leaving spaces into which the drawing would be later inserted or making a textual reference and then creating the drawing afterwards and leaving the possibility for fluid adaptations of either text or image later, synthesis as you rightly describe it. I often thought about a drawing and developed the idea in my mind while writing the story. So sometimes the order of these things is very difficult to convey. Sometimes the idea of a drawing might suddenly emerge anticipating the later events of the story, taking the story on another trajectory. Ideas for visual images, or actual visual images might come to mind and shape the development of the story. So there have been instances where the image and a textual passage have emerged simultaneously, out of an interrelationship where they mutually transform one another as I develop the story. For me this is partly why I want to explore this method and form further. While I think one could make comparisons with the relationship of script/ dialogue and image in film the use of visual images and prose is of a different order I think. The other obvious comparison of course is the comic book, which was very important to me in my childhood. Yet I also think William Blake’s use of images with words left its mark on me too. Are you working on some narrative at the moment? Talk about some of your future plans. Well, I’m rather superstitious about discussing creative plans. I have quite a major project in mind that I’m waiting for the right opportunity to get to grips with, so at the moment I’m working on something more immediately realisable. Currently I find myself working on many stories simultaneously, mainly short stories but a more substantial tale too concerning the origins of William Fetch, the protagonist of In Delirium’s Circle, yet I’m unable to reach a point where I’m able to look at conclusive drafts. This is entirely to do with personal circumstances that greatly limit the work I’m currently able to do. 2012 was a difficult year, intensely creative in one respect in finishing the work on my novel, yet at the same time terribly traumatic as a close friend of mine committed suicide which had terrible repercussions on my own circumstances too. I have to take courage though in the fact that I was able to deliver my novel under such duress. So I’m slowly working towards a collection of stories that I hope will be out in 2014. It’ll feature previously published stories that I’ve re-worked but also new unpublished work too. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research.

0 Comments

For the extremely active Jesuit Athanasius Kircher – collector of the exotic itens from the Past, Egyptian hieroglyphs peculiar descrambler, prodigious instruments designer – the play of light and shadow that simulates the movement and the life, that trick or effect that one day will be called Cinema, was very more than a base trick to deceive the senses. It was, rather, a peculiar way to interact with reality: something that was called at that time magic – the ways to access the positive or negative forms of Wonder and Nature. In the Dutch city of The Hague, not far from the home of Father Kircher in Rome, Christian Huygens, a notable Scientist in the fields of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy created a new way to project skeletons and ghosts in animated sequences – an exciting new game room with lights and images made by light. Both, Kircher and Huygens, were opponents located at the points of the sphere of knowledge ranging from Science to Quackery. Even so, in the case of the invention whose paternity is attributed to both, the magic lantern, the path traversed by either are the evil, death, and grotesque way, a possible uncontrollable route. The emblems of Kircher becomes dance of death in Huygens, imagination and Science conceptualization converge in grotesque images. This union of paradoxical facets, however complementary in some way, building a wonderful, technological, worthless and evil instrument emerges as central leitmotif of the new book by DP Watt, The Phantasmagorical Imperative & Other Fabrications. In this extraordinary book, each narrative emerges marked by tension between the prodigious and terrible, between the simple beauty of the obsolete/rare object and apocalyptic imagerie, between the elegiac evocation and ironic red smile, often soaked with blood.

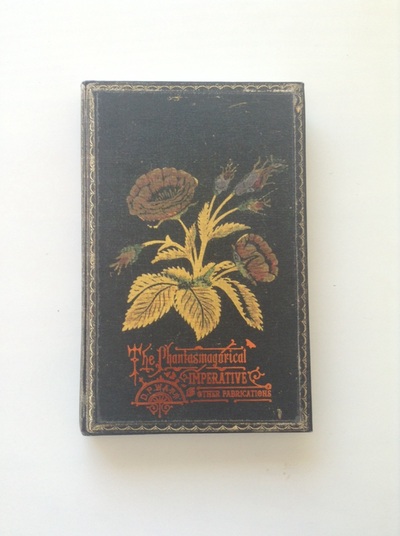

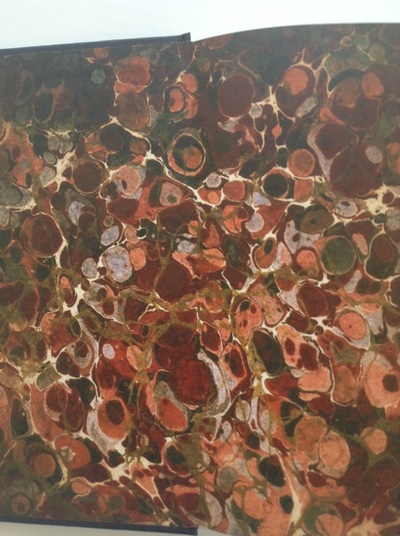

The D. P. Watt fiction is a new life form for an old insight that struck Heraclitus of Ephesus, for example: the awareness that there is a terror and a latent horror in the flow of dead objects that we believe are our objects and tools. Endlessly unable to break the chain of continuous metamorphoses, we suffered with the definitive loss of a solid identity that we believed so sound just a minute ago. So, the narratives that we find in The Phantasmagorical Imperative, superficially, could be seen as the collection of a beautiful and elaborate cabinet of curiosities. We have prestidigitation and metamorphosis, inanimate objects that come to life and vice versa, heavenly music from infernal instruments, photographic effects, and audio-visual transitions, faery landscapes from dreams and nightmares. But all this wild parade is just opening to the Watt real entertainment. These short stories protagonists – usually both witnesses, victims, executioners –, outsiders who have something moving: dissatisfied with the limitations of life, they found in some objects, instruments, miniatures and mirages new possibilities, perhaps what seems to be the only solution to the tedious cyclic continuum of the existence. Indeed, these objects these objects go far beyond the everyday, but not in the way our protagonists thought and this ironic solution summarizes the phantasmagorical imperative. Eugene Thacker mentioned in the afterword of the book, the Kantian notion of categorical imperative: the notion that we must act only according to a maxim which formulation is such that we want it to become Universal Law. That is an awesome and eerie resonance, a game of make-believe which aims to apply to the Ethics reign the made of steel invariable/intolerable and universal laws like those of Mathematics. Watt constantly reproduces the ambitious Kantian formula with some distressed and sinister results. The book The Phantasmagorical Imperative is a beautiful and fascinating object. The Egaeus Press exquisite edition evokes a refined object, although worn by use, found in the corner of an antiquarian. This effect is caused by the clever use of contemporary print reproduction technologies applied to a simulacra of the corrosive effects of time, an illusory game that anticipates those we see in the Watts plots: for example, there re, at the cover composition, the dimmed and toxic taste of obsolescence (the flower image, the typography), and the same happens with pagination and layout. The images reproduced in the edition are found objects, in the best Surrealist tradition, apparently torn photos and graphics (belonging to other books? Found on the street or anywhere else? Edited in software to look old and torn?). The history of this imagerie are truncated and finds a kind of mirror in the narratives – more than occasional illustrations, but comments linking the stories to fortuity, the usual way of mutation. The path that Mr. Watt chose to follow in his ferocious stories, to the endless reader delight. The Egaeus Press creator, writer, editor, Mark Beech would first be remembered as the publisher of the cult small literary zine Psychotrope at 1990s. Nowadays, with Egaeus Press, his vision is "moved by the concept of the world as a haunted house, and by the paradox of all life’s darkest fears and most ecstatic wonders being essentially one and the same.” (from the Egaeus Press website).

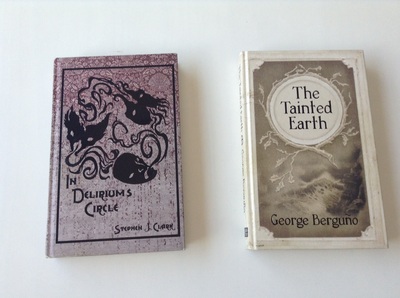

Although Egaeus Press is a young publish house, the first three book releases demonstrate breath and reasonably ambitious project. Could you tell a little more about the history of Egaeus? Perhaps the biggest considerations when starting Egaeus Press was wanting to stand out from other publishers. I wanted to hit the indie publishing scene fully formed and to make Egaeus Press books look and feel different from anything else that was out there - which was a little over-ambitious to be honest. From a business and design point of view, there are things I could have done better in those first months; and things I couldn't possibly have known without trying. But the books came out pretty well all in all, and I think I managed to stand out. I was of course very lucky to have Reggie Oliver, Stephen J. Clark and George Berguno for those first books. My own (very rare) writings had appeared in (quite obscure) anthologies alongside all three – although we had never communicated – which I think gave me the courage to get in touch with them, though I'm not sure it was much of a factor in their acceptance of my proposal. I explained what I hoped to achieve with the look and feel of Egaeus Press books, and I'm very pleased they trusted me. One of the most notable features of the Egaeus Press editions is it's the book design: illustrations, art, typography and book form mixed up in a rare harmony in a incredible way that the hardcover books seem lightweight and portable as paperbacks. What are the references for this exquisite graphic work? Some publisher in past as a influence? The only unifying factor in the design of Egaeus Press books is the impression of age; not necessarily of great antiquity, but of some other time. This isn't done through pastiche – and I don't think any Egaeus publication could be mistaken for an older book – but by using unfashionable design conventions and very simple things like header pagination and endpapers. I hope it works, in some intangible way on the reader – a hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck thing. I'm not sure I can name many publishers specifically as influential in the design of the book. I love old Edwardian children's novels and annuals because they are so over-designed, gaudy even. But evocative. Quality adult books of the era are often more austere, though there are some nice art nouveaux designs. No doubt these sort of books were not taken too seriously – likewise Victorian pulps are beautifully evocative. But just the dirt, the fade, and the library stamps in old books unintentionally add something evocative for me. With the design of Egaeus Press books I attempt to capture what elements of these sorts of designs and glitches work in a spine-tingling sense. Some publishers have a unifying vision or even a principle, a theoretical formulation that serves as some kind of guideline. There would be something similar in the case of Egaeus Press? It would be possible to define your editorial house with an idea, a word, a speculative notion? "Morbid and Fantastical Works" as the Egaeus Press subtitle says pretty much covers it. I don't like to spend too much time saying what I do and don't like to publish, because I too often these days come across writing which surprises me by defying its own limitations. There is a list of things on the website which it says Egaeus Press likes... including stuff like 'Clocks and clockwork', 'Crumbling ancestral homes' and 'The folk tales of Europe', but I was careful not to include what I don't like. As long as something 'feels' like it belongs to the kind of world Egaeus Press inhabits, then that's probably enough. Were there plans to expand the Egaeus Press catalog to other traditions of the fantastic: perhaps old authors or translations? If there is something, what would the authors that could be translated or published? The hardest thing is finding the time to expand Egaeus Press into areas I'd like to explore. At present I have enough going on to take me into the latter part of 2014, and ideas for projects beyond that. Another thing is that I like to be able to run ideas for the design of the books past the writers and make sure they have some input. It's become a very important part of what I'm doing. The books should have a little of the writer in them. To publish / republish / translate older books, perhaps by dead writers would require a different approach to the design. It's do-able, but it'd take some serious thought. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. In the Ex Occidente Press – a publish house with some works by D. P. Watt in its catalogue – web site, unfortunately nowadays deactivated, we found a small, but subtle and intriguing description about the author: “D.P. Watt is a writer living in the bowels of England. He balances his time between lecturing in drama and devising new ‘creative recipes’, ‘illegal’ and ‘heretical’ methods to resurrect a world of awful literary wonder. Recent appearances with Ex Occidente Press include his collection, An Emporium of Automata, in 2010, and tales in both Cinnabar’s Gnosis and The Master in Café Morphine. His first fiction collection, Pieces for Puppets and Other Cadavers (InkerMen Press) was first published in 2006 and reprinted in 2010.” The Watt’s fiction, in which the usual or unusual object appears as an element of amazement and uncanny, is very close to the heretical and illegal, in fact. The first steps in this unsound but fascinating universe can be followed at his Interlude House.

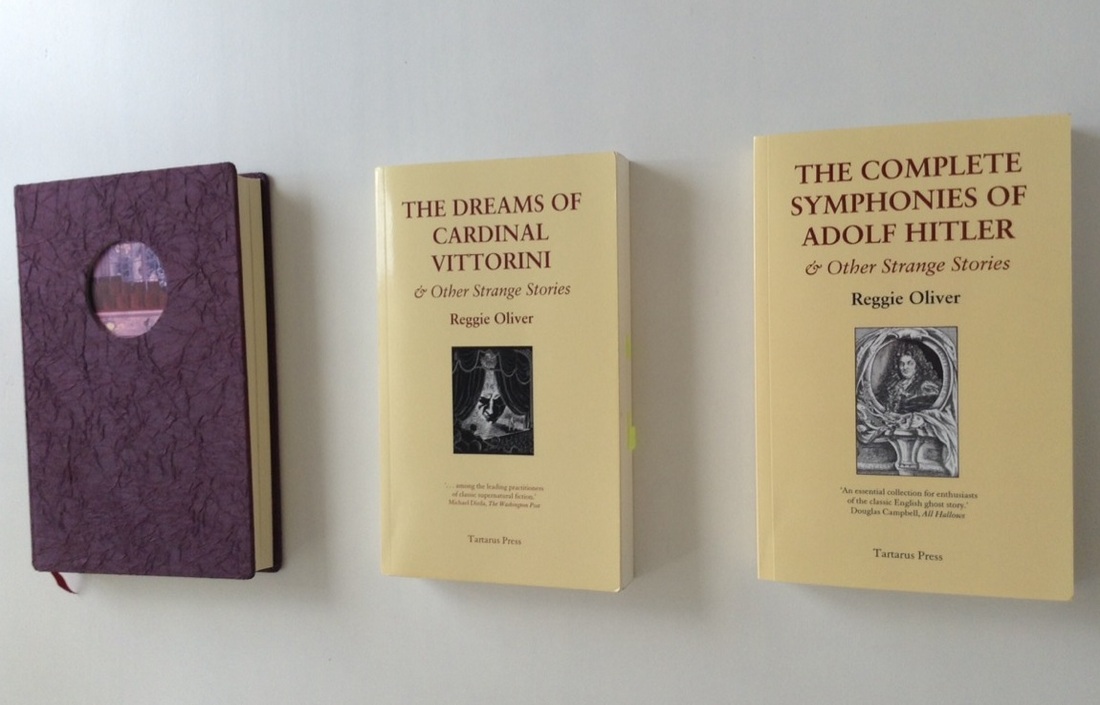

Your fiction (I take as an example your The Ten Dictates of Alfred Tesseller, a wonderful novella full of transformations), has an ingenious structure, in which there are moments when the reality seems stable with moments of full transfiguration – that's the best word I can find for your fiction effect –, with several elements of that reality changed in new and complex forms. This process/mechanism is the narrative itself, in same way. Surrealism seems to be the initial reference, but not the only one. There is a shift to the free form narrative, more freer than what we see in some cyclical narratives like in Alain Robbe-Grillet, but your narrative reserves a clear plan, far from cut ups or free association that we found in William S. Burroughs. Could you comment a little bit about this process of composition and the references that uses in it? It is difficult to comment on Tesseller, as this novella is a very particular case. There I was attempting to experiment with different perspectives of narrative from a position of flux. The being narrating it is engaged with the reader directly, claiming to have known them in youth, but also they are our connection to Tesseller, himself a consciousness in flight, beyond the grave. Each section is driven by its attempt to create that sense of another transformation without losing the overall coherence of the plot around Tesseller. In parts it succeeds, in others it becomes a little mired in some of the more poetic aspects I was trying to introduce. The transformation of reality is important to me, yes, but this comes, in many ways, more from the theatre than it does from literature. The process of composition changes with each story, and I have no particular allegiance to any movement, nor indeed anything as well-formed as a technique that I can deploy. My writing seems now to be more driven by scenes that emerge as I am working. Sometimes these can develop relatively coherently and chronologically, at other points they are very separate and can take many months to piece together, sometimes even swapping over from one story to another. I mentioned in the previous question, the terms "ingenious structure" and "mechanism" and, in certain way, your fiction seems fascinated by these elements. But it seems to me that your focus is not gigantic engineering works, openly devouring humans (which we see in certain fiction of the 1970s, as the mobile city in the novel The Inverted World by Christopher Priest or the highway infernal maze in J. G. Ballard's Concrete Island), but the works with subtle engineering, the smaller scale employed to deceive the perception postulated by everyday reality: the effects of prestidigitation, the cinematographer, the praxinoscope, automata, ventriloquist puppets, etc. What would be the source of this fascination? Yes, this is right. I am not that interested in timeless monsters from the nether regions of space or zombie apocalypses—although they can be fun. I find there are far too many monsters and apocalyptic tendencies within each of us. I am interested in how the ‘everyday reality’ you mention and those smaller moments contribute to a larger effect though. The strange, weird, supernatural, whatever you would like to call it, is happening all around us. Not as a manifestation of something, or somewhere, else, but rather as an example of our own otherness; those hidden and devious methods through which we manipulate, control, hurt and subjugate others. Puppets, vent dummies, magic tricks etc. are means by which to explore self-deception through that sliding, fading, or failing perception of the world. As I mentioned above it is the world of performance that has influenced me more than anything—Strindberg’s Dream Play, Jarry’s Ubu Roi, Gordon Craig’s uber-marionette and Kantor’s bio-object. In the puppet theatre and the carnival, or fairground, we find an alternate reality that seeks so hard to entertain through showmanship; just by twisting the performative slightly one can distort the real and explore our relationship to those things that we seem to find so fascinating and frightening; sex, death and nostalgia (or dreams). That all sounds very grand. It is not meant to be—quite the opposite in fact. It is from these minor, devalued things, slight experiences, supposedly unimportant ‘entertaining’ events, that I think fiction can comment upon the world with humour—by disrupting the real, playfully and experimentally. In this sense, the cinema seems to occupy an interesting place: the moving picture appears to broaden the infinite possibilities of deception and this is replicated in your fiction. I have in mind, in this regard, especially your short story "Dr. Dapertutto's Saturnalia". This impression has some basis? In this sense, what author or cinema style often useful as your inspiration? I’m intrigued there by your use of the word deception in relation to cinema. It seems to me that writing is also manipulative and it must be aware of the timeframe it operates in just as much as cinema. This is what interests me most about the relationship between author and reader. As much as you may work at the pace of writing it cannot deliver this in the same manner as a work for the screen. Pace might be manipulated in minor ways, perspectives shift back and forth, but it requires more control and patience to generate something that is not simply a confused wreck. Film can, as in many ways the theatre can too, always rely upon its visual aspects to further control meaning and, as you say, “deceive". Where lengthy descriptive elements in fiction intervene they can be either revelatory or calamitous, by that I mean unnecessarily disruptive, especially in short fiction. The form of film work that most interests me is animation, especially the works of makers such as Starewicz, Barta, Svankmajer, Norstein and the Quays. Its artifice is obvious, its materials frequently poor; rubbish, broken wood, discarded toys, rusted metals, meat, dust and dirt. From this they elaborate magical transformations through a painfully slow process. Charles Patin, in his letters to the Duke of Brunswick, describes a magic lantern show, patenting the famous phrase "l'art trompeur" to characterize this strange spectacle in which convergent images "rolling about in the darkness". That expression reminds me quite your fiction, in which visual and descriptive elements seems essential as structuring the plot, however these visual artifacts soon proves fallacious. How about the relationship between visual, descriptive and literal elements in your narratives? You use some visual procedure (image or object found, for example) in preparation? Often the writing starts from a particular object, or image. At the moment I am very interested in cartes-de-visite and have just completed a story, "By Nature’s Power Enshrined", based upon a chance find of a particular card. The staged environment of the early photographic studio fascinates me. The patience to produce something quite akin to a painting, and the careful balance of components that give meaning, such as the backdrops, the props etc. Now that we merrily snap away every second of our lives and then distribute the images widely to those we know neither well, nor closely, seems to lose some of the care of the staged image. I suppose a scene in a story also goes through processes of ‘rolling about in the darkness’, both in the mind of the writer and the reader. Its coming to clarity is not guaranteed on either side. If it survives as an image that intrigues and provokes thought, much as the magic lantern, then that may well be enough. There is certainly nothing as elaborate, or controlled, as a procedure. Sometimes an object, or image, may be too close or too known, and that can be difficult to work with. I prefer things that call a little to be reworked, or explored, through a piece of writing. One of his last works, published by Egaeus Press, was this narrative piece about the transfiguration of the Mr. Punch, this strange and curious theatrical plot on violence and crime for children. In fact, it seems to me that your fictional universe is very close to the spirit of this ancient popular work. Your approach to the ancient sources is often more intuitively, transforming them into symbols, or you prefer an approach based on historical research and some archeology? Yes, Mr Punch is close to me, as are all puppets, but there is something especially enduring about the way that Punch has travelled, popping up in his various guises around the place. His violence speaks of the drive to become oneself, at the expense of other selves, and maybe some of my stories explore that tension between an ethical compulsion to eradicate self and the relentless urge to make one’s presence known to the world. Certainly there is historical research, but again this occurs rather chaotically and I attempt rather to draw out, maybe ‘intuitively’, maybe through ‘symbols’, those aspects of a particular historical incident, life, or span of culture, that—through fiction—might be seen to be grotesque versions of our reality. Are there any plans in adapting your work for the cinema or another audiovisual, theatrical or multimedia expression? There are no current plans for adaptations of my work in any format. Well, nobody has approached me about it anyway! I would enjoy seeing some short films of stories, especially those that might evoke some of the strangeness of objects that has always fascinated me. As a final question, it would be interesting to know the authors, past and present, that you admire or consider important for the construction of your narrative style. When I began writing prose I attempted something along the lines of Beckettian narratives, but without any of the skill to extract and edit to the point of absolute purity of expression. At the point that I relaxed and no longer attempted to emulate the works of those I admired I think I began to enjoy reading again—when it was no longer about learning, but appreciating the work for what it did, rather than how I might attempt to deploy it. Given that, I wouldn’t know where to start in charting what might be important in how my narrative style has developed from other authors. Perhaps it is enough simply to cite some of those authors whose work has particularly struck me. My main interests focus upon European writers, particularly E.T.A. Hoffmann, Maurice Blanchot, Stefan Grabinski, Franz Kafka and Bruno Schulz. My interest in “weird" writers is fairly predictable, including Arthur Machen, Robert Aickman, Sarban and M. John Harrison. There are so many contemporary writers whose work I have been enjoying, including Michael Cisco, Jonathan Wood and Derek John’s work in particular. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. mong the narrative tools universe, the dialogue stands as one of the most complex and fertile: this interaction between the characters through communication devices (immediate or not) allows the oscillation between the said and the unsaid, expressed and hidden, true and false, intentionality and involuntary. At the same time, the dialogue connects the flow of human existence in narrative terms mimicking the numerous discussions that impart (or not) our existence with meaning. The drama, no doubt, places this tool at its center, but it arises in other conceptions of plot; for example, the philosophical dialogue since Plato, who knew how to put the dialogue in the service of philosophical exposition and irony, the element that dialogue facilitates and enhances. In this sense, the playwright, biographer, short story writer and novelist Reggie Oliver captures both the theatrical tradition and the use of dialogue as a tool to improve the irony impact, and it is one of the most skilled contemporary writers using the powerful tool of dialogue in his plots. Accomplished atmosphere builder both in short stories (in collections like The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini or The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler, both by Tartarus Press) and romances (The Dracula Papers, Book I: The Scholar’s Tale by Chômu Press and Virtue in Danger by Ex Occidente and Zagava Press) endow his ghostly plots of fierce urgency and complexity – unfortunately rare in contemporary literature.

The theatrical universe arises in many of your stories, some like elements essential to the atmosphere and ambience. However, there are plots such as, for example, "The Black Cathedral" or "Evil Eye" which, although far of that theatre atmosphere had some theatrical aspects and complex scenes. It seems to me that in this sense, the dialogues appear as the key element in such a process, the dialogue as the way to the revelation small or big details. You could talk about how is the development of dialogues in your plots. I began my writing career as a playwright, although I was writing prose fiction as well, but my first professionally published works were plays. I have continued to write plays and have had some success also with translations or adaptations of French plays. What I enjoy about the use of dialogue is that it can show or suggest without stating. This sets up a relationship with the reader who can pick up on what is happening without being told. To give a simple example. I could say simply X was very angry but pretended not to be. Or I could suggest it by dialogue by having Y saying: “You’re not angry, are you?” And X saying: “No, I’m not angry! Of course not! I’m not angry at all.” That way, you not only make the scene more alive, you manage to suggest all sorts of things without spelling it out, like X’s irritability, his hypocrisy, his possible self-deception etc. etc. It is a primary principle with me that readers should be given the space to have their own views of events, to work things out for themselves. In “Evil Eye” which, as you perceptively point out has theatrical reverberations, I was concerned with ideas about spectators and participants. A spectator merely by spectating can alter the character of what happens. Perhaps one could go so far as to say that there are no such things as spectators, only active or passive participants. Also, the theatre universe appear as a backdrop for some of your stories seems so detailed to the reader that suggest a profound experience with such a universe, a deep knowledge about the daily out of scenes dramas and questions. It is a reflection of your personal and professional experiences, or a matter of search/retrieval literary backstage narratives and plots? In any case, what about the maturation process and research in plots like “The Copper Wig” or “The Skins”? My mother was an actress and I grew up around theatres. I have always loved everything about the theatre, particularly this interplay between illusion of reality. Stories are derived partly from my own experience, partly from stories I have picked up from my mother or old actors and actresses I have worked with. Performers, when not acting, are great story tellers. For example “The Copper Wig” which is set in the 1890s, derives from a number of sources. I talked with various actors who had been in the profession before this first world war and they gave me odd little details which bring the story to life, like the theatrical Sunday trains which were often met by theatrical landladies touting for custom. The detail about lying in bed in the morning and listening to the clatter of clogs on cobble stones as the mill workers went to the factory I got from my mother. On the other hand the copper wig itself I got from my own experience. I once shared a dressing room with a bald old actor who had a variety of wigs which he had neatly arranged on wig blocks, looking, from the back, like a row of neatly severed heads. The one that particularly fascinated me was a bright copper colour which gleamed under the strong dressing room lights. “The Skins” derives partly from playing the “skins” part in pantomime of King Rat in Dick Whittington, partly from the memory of a husband and wife variety act I once worked with. I am interested in the “quiet desperation” of most lives lived in the theatre: not the stars who achieve fame and success but the moderately talented people who just keep going. I am interested in how we bear our own mediocrity. One of your stories that impressed me most was "The Boy in Green Velvet", because there is in it a universe of suggestions which we have only a vague perception, a human vileness so terrible in which the supernatural element appears only as a catalyst. The same impression astonishing, indeed, I had to read another of your flawless narratives towards construction aspects, "The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini". Both plots, moreover, using unreal objects or almost unreal (paper theatre toy, memories of a lost book) in the construction of the narrative. In your opinion, this suggestive effects would rises from the objects in the scenery? As a note, when I visited the Benjamin Pollock's Toy Shop in Covent Garden, his short story "The Boy in Green Velvet" appeared, materialised before my eyes. The toy theatre – a very English phenomenon, though it has been picked up on the continent – has always fascinated me. I think it was because of the very peculiar and strange world it evoked of 19th century theatre before the advent of “realism”. In “The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini” I used various manuscripts and documents to give us a glimpse into worlds very different from ours, strange and terrible ones, which throw back a strangely distorted image of our reality. Human beings can be very responsible for the world in which they live: the worlds of Alfred Vilier and Cardinal Vittorini in “The Boy in Green Velvet” and “The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini” respectively are fearsome and not like our own, I hope, but they have the power to infect our world, and this is interesting to me. A persistent theme in my stories, very much taken from life, is the way people with powerful egos can, if one is not careful, take over another person’s life. What difference do you feel in terms of building between shorter and longer plots, like the tales of the collections by Tartarus Press and the novels like Virtue in Danger (whose subtitle is quite suggestive, The Metaphysical Romance)? Have you any preference among these formats? My tendency has been towards the form of the longer short story or the novella in which there are several “acts” but where a single theme or image can be held to without tiring out the reader. In my two novels The Dracula Papers and Virtue in Danger I have created a world, a microcosm, in which the events occur. In the case of Virtue in Danger I have created quite a narrow and circumscribed world – the headquarters in Switzerland of a religious “cult”, but to populate it I have created a large cast of characters and a wide range of action from tragic to farcical. The short story is the most powerful medium for evoking a mood, an atmosphere, a character. In the longer form of the novel that mood or atmosphere becomes dissipated or simply too oppressive for the reader. Chekhov, Maupassant and Walter de la Mare, to name three of the greatest short story writers of all time, are all masters of mood and atmosphere. You seem comfortable in working with phantasmagorical elements associated with contemporary gadgets, from TVs to video-game consoles, which is curious because many imaginative contemporary authors (as Mark Valentine or D. P. Watt, for example) seem to prefer older gadgets or objects of another nature. How did this your resourcefulness with these new phantasmagoria objects? I believe in a metaphysical realm. I prefer the word metaphysical to supernatural because I do not see it as somehow “super”, that is above nature, but rather working “meta” alongside the physical world. In my view it is a living reality, and therefore just as likely to emerge from a computer as from an ancient grimoire. Modern technology moreover is constantly trespassing on the ancient world of magic. A few hundred years ago something like a television would have been seen as a “magical” and deeply sinister object. Equally Dr Dee’s “scrying stone” might be looked on by us as a kind of primitive television. All technology, moreover, is a two edged sword. The surveillance equipment, for example, in “Evil Eye” can be used for good or, in the case of the story, utterly malign purposes and can therefore be imbued with the evil of its abusers. In your most recent novel, Virtue in Danger, there is a quasi-religious movement and a rich row of characters, both seem emerging from a film by Luis Buñuel. Some critics, as D. F. Lewis, speech in some Hitchcockian ambience and complexities in this novel as well. Could you talk about the building of this characters in particular? Is there any cinematographic influences? Interesting you should say that because I have also written Virtue in Danger as a film script. It’s promising but far too long and I am consulting with people who are more expert in film than I about it. I naturally see story cinematically - in other word in “scenes” with close-ups, wide shots, montages, “dissolves” and the like. When writing for me really works it is often like simply describing and transcribing the dialogue from a film showing in my head. Many of the characters in this book are very loosely derived from actual historical figures most of whom I never met. But I got an impression of them from their writings and anecdotes about them told by people who met them. The key for me with characters is always speech. If I can hear them talking, then I know they have come alive. With the central character of Bayard, for example, it was that weird mixture of public school heartiness and quasi-religious pietism in his speech which unlocked his character and its inherent contradictions. People often inadvertently reveal most about themselves when they are being insincere. One of the elements that makes your stories remarkably is undoubtedly your work in graphic illustrations that dialogue with the fictional universe of the text. In this sense, moreover, is not just to “enlighten” the text, but use the visual element as a meaning boost to the expressed in the plot. In this sense, how is your illustration construction work? You write the story and then leans over to synthesis it in images or vice versa? The image is always made afterwards when the story is complete. The business of making illustrations for the story collection is done when all the stories are written and a table of contents drawn up. I enjoy doing the drawings very much because I can listen to music while working on them. I cannot possibly listen to music while writing. I never make the drawings simple illustrations of an event in the story; rather they are an impressionistic rendering of one or more of the story’s images. They therefore provide a reflection on, or an insight into the story. Here is my idea of the story, I am saying. It may give you a further insight, but it is not definitive; it is no more valid than yours, the reader’s. The chief means for understanding the story should be the reader’s imagination; my drawings are simply a little additional spy hole onto it. I have come to value them increasingly as part of the experience over the years, and I am aware that they have helped to distinguish me from others working in the genre! The irony is an effect that seems to me to arise from varied and complex ways in your short stories and novels. The way it appears, for example, in “The Golden Basilica”, “Lapland Nights” or “The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler” is almost like the philosophical work towards the destruction of apparent meanings towards new possibilities – something close to the idea of irony in Kierkegaard for example, that stated about the “life worthy of man” starting by the irony. The effect of irony in his plots possess an imaginative or philosophical source? Jules Renard in his journal wrote: “Irony does not dry up the grass. It just burns off the weeds.” I agree. Irony is the conscious expression of a realisation that there exists a gap between human illusion and reality. No truly serious writer can lack a sense of irony, but that should not preclude compassion. We should be aware of the “vanity of human wishes” and the emptiness of most human achievement, but this should not prevent us from feeling sad about it. “Life is a comedy to those who think and a tragedy to those who feel,” wrote Horace Walpole. To a writer it should be both tragedy and comedy, and often simultaneously. To put it another way, both detachment and empathy are necessary. My aunt, the novelist and poet Stella Gibbons, would often discuss these ideas with me. She derived this from her reading of the writer she most admired, Marcel Proust. Is there any interest in you towards the creation of imaginative/strange/weird fiction for theatre or film, for example? How would you believe his plots will work in audio-visual or theatrical fields? There is. I began life after all as a playwright. It is an area which I hope to explore more fully in the coming years. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed