|

In the film Andrei Rublev (1966) directed by Andrei Tarkovsky there is a curious scene, bizarre though valid and feasible from the point of view of a cinematographic work that was intended to be a historical reconstitution of the invisible, that is, the life of Andrei Rublev, the enigmatic Russian artist who lived in the fourteenth century, acclaimed as the most important and recognized icon painter in the History of Russia. When one character in the film, Kirill – another icon painter, extremely erudite and bookish – back to his monastery after years of wandering (recounted in episode 6, “Charity”), he realizes that a group of horsemen are being projected projected upside down on the wall opposite to the window which is closed by heavy shutters. Despite the barriers in the darkened room's window, there is space for the entrance of a tiny light beam, responsible for the marvelous and brief projection. A mediocre painter of icons, Kirill intuitively discovered the secret that afflicted the art from ancient Greece in this ad hoc camera obscura: the discovery of a method for capturing the movement of life, shaped in moving pictures. But that's not enough for Kirill to escape his own mediocrity – although inventive, he would never emulate/rival Andrei Rublev, a painter who did not need technical apparatus, narrow references in the tradition or prefabricated epiphanies. What Rublev did was paint a vision – the reality of the universe and the imagination – which only he had, something inaccessible to reproduction, even if a very sophisticated technique were employed. But humanity would pursue in devices and technological utopias the views articulated by Andrei Rublev (or Michelangelo, or William Blake, or Francisco de Goya, or Vincent Van Gogh, or Francis Bacon): cinema is perhaps the most stupendous result of this millennial effort that is both an attempt to capture the movement of life as a way to reproduce visions which we have access to only in the contemplation of great paintings or unique epiphanies.

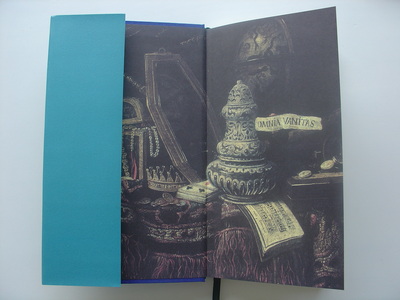

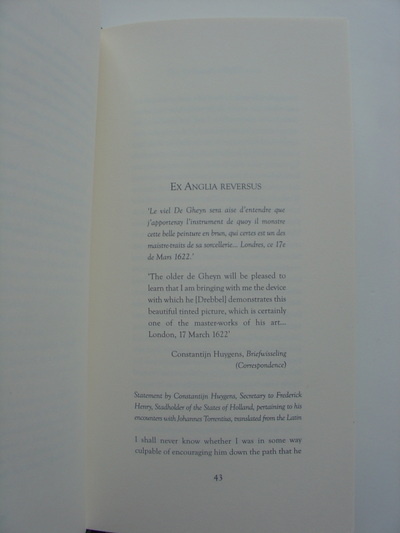

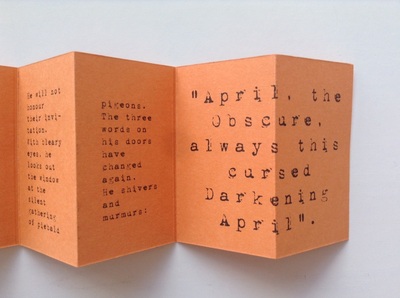

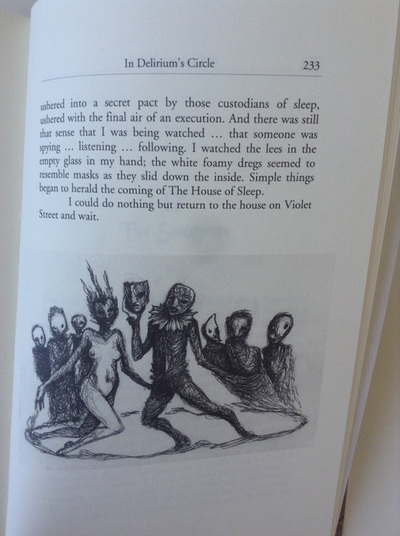

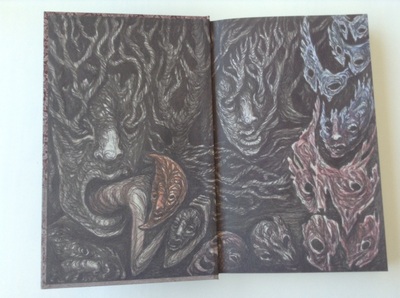

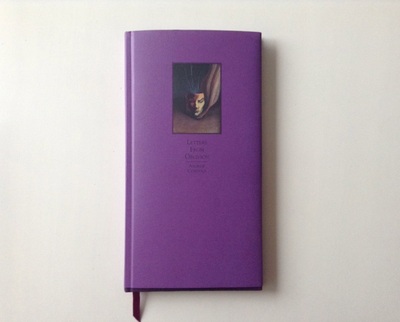

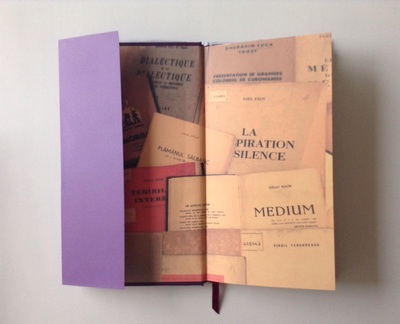

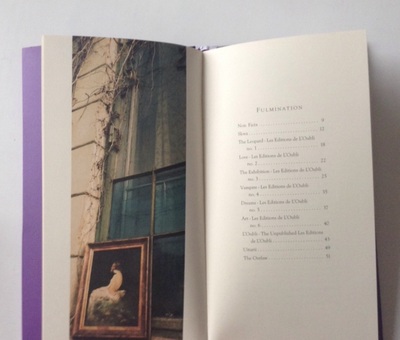

It is curious that this intuitive discovery in Tarkovsky's film, although entirely fictional, is still achievable. The history and origins of the camera obscura are large, mythical and erratic, appearing in ancient China and in the Aristotle's researches, in the medieval Arab Engineering treatises and in the experiments by Anthemius of Tralles, the mathematician who designed Hagia Sophia in the days when Istanbul was still called Constantinople. The Ancestral Skyline of History has some fixed points with conventional nomenclatures, so in the context of what we usually call “Antiquity" and the "Middle Ages” – general names for didactic purposes – the knowledge protruded from much more complicated paths that nowadays, with unifying processes, databases, instant media, systematical records or patents. The obscure details and possibilities of the past added to the desire to achieve what might be called absolute image – a paradox which brought together the perfect reproduction and the imaginative vision of complete beauty – is what fuels the extraordinary novel by Brian Howell, The Stream & The Torrent (subtitled The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius and the Followers of Rosy Cross: Vol. 1), released by Zagava/Ex Occidente Press collection Les Éditions de L'Oubli in 2014. It should be noted that Brian Howell is not a newcomer: he delved into the intricate and fascinating cultural universe of the seventeenth century (with a focus on Vermeer) in his first novel, The Dance of Geometry (2002). He also wrote a short stories collection on contemporary Japan, The Sound of White Ants (2004), recovering both Japan's tradition in his foreigner’s point of view in the style of Lafcadio Hearn and the works of Yukio Mishima. In The Stream & The Torrent, Howell returns to the world of artists, scientists, inventors, noblemen, conspirators and charlatans of the seventeenth century, but the focus is no longer a well-known painter. Johannes Torrentius (1589-1644) – who has adopted a Latinized and slightly modified version of his Christian name, Johannes van der Beeck Symonsz, in which “Beeck” means “brook” – was considered a master in Still Life already in his time, but this recognition did not prevent much of his works being burned due to accusations that the painter was a member of the Rosicrucian Order, an adherent of atheists and Satanist beliefs. The reputation of Torrentius preceded him: he was seen as “seducer of burghers, a deceiver of the people, a plague on the youth, a violator of women, a squanderer of his own and other’ money”. He stated that his works paints were “other", his paintings were the result of some kind of magic, that "it is not me who paints”. Eccentric and arrogant, he was arrested, tortured and condemned to the stake. He was saved by the king of England, Charles I, and became his protégé in 1630. For some time, Torrentius lived alone in England, at the expense of its powerful new boss. But in 1642, he had to leave his comfortable exile in London, perhaps due to the perception that the recently started English Civil War would lead his patron, fatally, to be beheaded. Torrentius returned to the Netherlands and was arrested again for some time; finally released, he went to his mother's home to die, some say due to a relentless syphilis infection. A February 7, 1644, he was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), a remarkable fact when considering the rumors about the deceased and his atheism, heresy, blasphemy and devil worship. His works have disappeared without a trace: part of them in the first imprisonment. Some works could have survived through the English exile; in fact, the inventory of Charles I mentions several paintings by Torrentius but none were found later. Only one of his works survived to be discovered in the twentieth century: Emblematic Still Life with Flagon, Glass, Jug and Bridle (1614), an extraordinary and complex allegory of moderation. The reflections' shadow-play in every surface of this painting – metal, glass, wood – seems to build a fiery and dark universe of fantasy through strange shadows and mysterious ways. This amazing painting, the only work by Torrentius that has come down to our time, it is one of the central devices in Howell's novel. The Stream & The Torrent is divided into three chapters: “Vandike and I”, “Ex Anglia Reversus” (poetically evocative and powerful expression, which was for some time the working title of the book) and “Cornelis Drubelsius Alcmariensis”. Each chapter presents a fragment of the mysterious life and work of Johannes Torrentius from a privileged witness’s point of view. In the first chapter, the very Johannes Torrentius, in a kind of diary, describes his exile in England and attempts to retrace his artificial and complicated processes to capture the life in images with blood, magic and a sort of art. In "Ex Anglia Reversus", the witness is Constantijn Huygens (father of the scientist Christiaan Huygens, inventor of a device which was the precursor to the cinema called the magic lantern, according to the historian Laurent Mannoni's researches in his book The Great Art Of Light And Shadow), the arbitrator in a strange duel of still lifes between Torrentius and the father and son De Gheyn. Finally, in the last chapter, the testimony of Cornelis Drebbel of Alkmaar, renowned for inventing the oven thermostat and for the construction of the first functional submarine; Drebbel reports his experiments alongside Jan Torrentius in London and Prague to the powerful final narrative hook. Historical characters intersecting each other in contexts not only credible but feasible: there are political games, palace intrigues, aesthetic discussions and bizarre/useless or cruel (depending on the point of view) inventions. This is a complex narrative texture, centered in fragmentary testimonies: the uncertainty of first-person narrative is multiplied by authors' distortions and manipulations, as well as the perception and reading of every fragment. The elaborate poetic construction made by dubious patches and a testimony that apparently can only be taken as true after a process of systematic collation – exactly what remains of Johannes Torrentius fascinating personality. Above all, the novel The Stream & The Torrent is a brilliant allegory of cinema, the human dream (achieved thanks to the technology) to capture life in all its detail, as through a dark process of black magic. In this sense, Brian Howell approaches Adolfo Bioy Casares novel The Invention of Morel, but exceeds the Argentine author to work not with pure fantasy invention of a machine that captures the substances and then plays this substance endlessly through a perpetuum mobile mechanism. Wonderful idea/image, but also conventional. Johannes Torrentius's “other paints” and camera obscura have an unstable concreteness provided by historical accounts, vague memories and dubious records; it is both a feasible (but unrecoverable) invention, a fraud, a hoax, a sleight of hand, a prodigy. The book, physically, follows the standard defined by the editors Dan Ghetu and Jonas Ploeger: it is an indisputably beautiful work of art. The printing is magnificent, on heavy paper with balanced typography, which reminds us of an updated version of the books that Torrentius and his friends manipulated in the seventeenth century. The internal images – curiously, none of them made by Torrentius – are beautiful still lifes of the seventeenth century, which guarantee to preserve a fully adequate air of mystery. We can only wish that the second volume is released soon, so let us enjoy the delicious, turbulent and atrocious Johannes Torrentius and his adventures in his quest for the absolute image while traversing the intricate conspiracies of this imaginary Rosicrucian Order. NOTE: Some of the historical references in the article above – especially about Johannes Torrentius – came from a series of articles (in three parts) quite enlightening by Maaike Dirkx entitled “The remarkable case of Johannes Torrentius” available at https://arthistoriesroom.wordpress.com/?s=Torrentius&submit=Search. The excellent review by Des Lewis, available on his website (https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/2014/10/24/the-stream-the-torrent/) is very useful and intriguing as well.

1 Comment

Richard P. Martin in his introductory study about Homer's Odyssey in the Edward McCrorie translation mentioned how some variation in the remaining Greek epic poem manuscripts opens a possibility of another kind of Odyssey. Because Athena, in the first canto, makes clear her intention to inspire the young Telemachus, son of Odysseus, to seek his father's whereabouts information between the Greek kings and military leaders who had returned from Troy. The cardinal points of this search, the “telemachy”, are well known: Sparta and Pylos, whose kings who gave testimonies were, respectively, Menelaus and Nestor. But in some surviving manuscripts Athena would instruct Telemachus to visit at least one more city, Crete, governed by Idomeneus. Martin then wonders if there would be a longer version of the Odyssey, which was lost in the Limbo of History, in some obscure process of textual revision probably caused by dark oscillation in which a portion – impossible to determine whether significant or irrelevant – of the poem totality was lost, probably forever. It is true that this loss survives somewhat in the and interstices more or less noticeable, in traces evoked by archaeological accuracy. Martin says, however, that there will always be something like “a provocation” in this residuum: the potential revival of the lost unknown and sectioned part, somewhere, revealing to us something new about Odyssey, allowing a new vision to the Homeric poem. The lost text stirs our curiosity and opens a breach in the stable perceptions of Literature, History, Knowledge, of the Universe. The lost, ignored, destroyed – in a word, potential – book seems to contain, at least for your achievable reader, a portion of divine revelation.

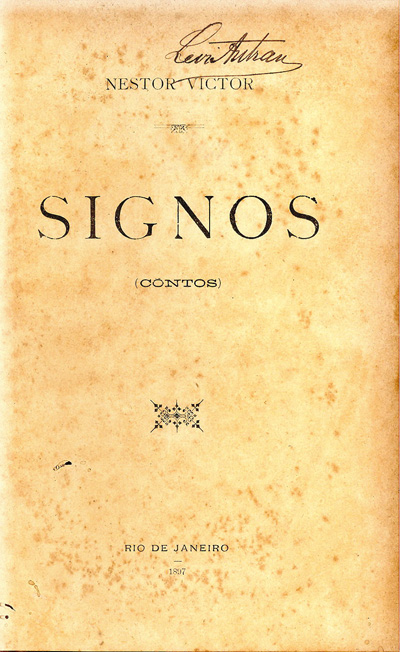

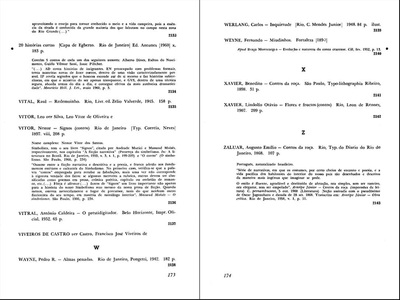

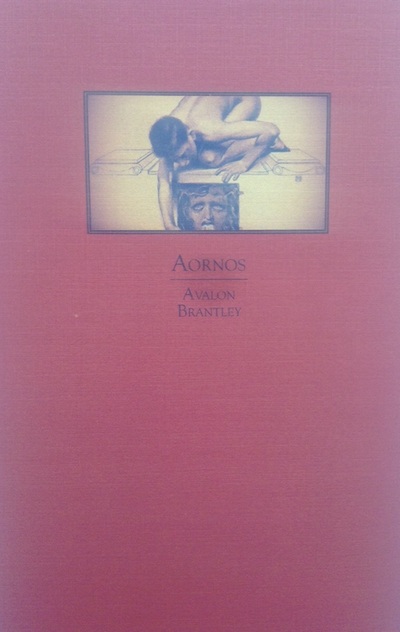

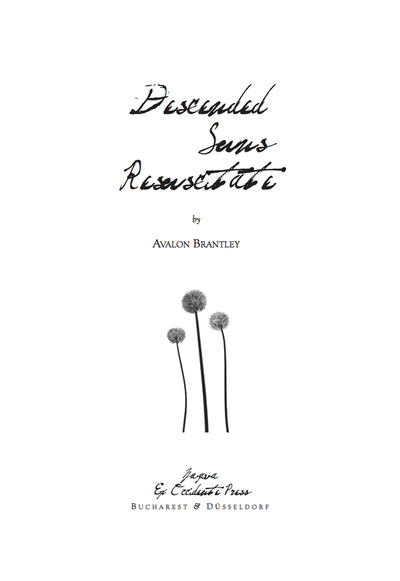

Interestingly enough the same ecstatic feeling on the discovery of a lost work of art, a landscape narrative truncated with blanks, is common in research and restorations made by film historians. Perhaps certain nearness to the Literature as idea through narrative conceptions make the cinematic restoration efforts more dramatic, indeed. Copies of rare and almost extinct movies have been found in basements, abandoned military wagons and other places even more unlikely. The extreme weariness of certain ancient films requires new procedures, technologies and approaches for this fragile, even flammable, material. A film like Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1926), for example, has a restorations history so long and complex since its launch until today (because a more complete version of Lang's film was found in 2008 at Buenos Aires Film Archive) that turns into a kind of contemporary legend and the search for the pieces of that film around the world in order to constitute a totality, the modern quest for the Holy Grail. Partially recovered films – some survived in the form of sequenced frames as the case of Bhezin Meadow (1935) directed by Sergei Eisenstein – excite the viewer's imagination in the same way as the records of a different telemachy excite Homer readers: what would be possible if that fragment there really being, the considerations about the consequences of such impossible discovery. A search for a meaning in a utopian form of discovery, the permanent reestablishment of a fragment of the past – or, at least, the evocation of what was lost – moves the archival explorers seeking to recover undeniable beauty files from the wreckage of repeated historical storms. In the process, they found obscure and esoteric references, evidence so disjointed and difficult to track so that apparently the field of historical research was lost and apparently the path is a deep swimming in the fragments of humanity's collective dream (or nightmare), embodied in an artistic shape. We might call the uncertain results of these endless investigations – ever incomplete because completeness of surveys a immense magnitude, such as the absolute recovery of the past – with a name: archival fictions. The fiction here is not only an extrapolation of historical reality given by narrative and mimetic resources. For authors such as Jorge Luis Borges, fictionalizing is to build a coherent, self-explanatory universe, methodically arranged by complex and peculiar laws, which can be shared with the everyday reality. Thus, in the Book of Imaginary Beings prologue, Borges proposed an interesting reflection on how the data from reality work to formar our perception of the wildlife at the zoo in a way far from a vision/experience of absolute terror for a child but rather a quiet journey full with wonder and even tenderness, so the trip to the zoo is usually listed as a childhood amusement. Borges then offers successive imaginative explanations for the zoo situation described by him, all at once valid and false, linked to common sense or the great traditions of philosophical thought from Plato to Schopenhauer. Fiction, accordingly, gets the curious status of a functional interpretative possibility of the reality captured by our senses and/or our consciousness since the core and raw data from reality would mean nothing without our interpretive activity. The researcher whose work relates to what we define here as archival fiction therefore works on the boundaries between reality, historical record, memory and fiction, especially when you need to describe or reconstruct some elements from the oblivion, such as biographies, trajectories, possible destinations. Therefore, the archival fictionist must exceed the literary discourse usual limits: the speculative essay runs through the borders of narrative, remembrance approaches the historical reflection, the description becomes, without warning, a poetic projection. An archival fiction archeology is a task that remains to be done, but we can say that one of his patrons is the aforementioned Jorge Luis Borges. Borges's creations put the instances of literary discourse on a unstable state, moving from a paradox to another paradox: in the borgean canon, there are imaginative fables that could be literary studies (as in the story "Pierre Menard, Author del Quijote"), philosophical essays with certain poetic resonance and narrative (Historia de la eternidad), cultural studies that plunge into the depths of imagination for new interactions and forms (Qué es el budismo?, with Alicia Jurado). Currently, some remarkable authors transiting through this equivocal universe noteworthy. Luiz Nazario, in Brazil, working with the records provided by the film, literary and philosophical imagination, especially when abandoned, overlooked or relegated to the unjust oblivion. In Europe, authors such as Mark Valentine (with two recent archival works, Wraiths and And I’d Be the King of China) and Andrew Condous (Letters from Oblivion) – whose themes are, respectively, the English decadence nineties in the last decade of the nineteenth century and the Romanian Surrealist group Infra-noir – conduct a complex recovery of obscure moments in literature, even emulating the style and perspective of their objects, seeking nearly the reproduction of definitely lost works and aborted projects. This is an impressive demonstration of the suggestive power of archival fiction, exploring the imagination and the human desire made in books (or films, or paints, or photographs), especially those missing on the fierce History skyline. At the gallery below, the frontispiece of Nestor Vítor's Signos, masterpiece of symbolist narrative in Brazil, and a brief book description by the Proceedings of the National Library (Anais da Biblioteca Nacional, vol. 87, 1967). This is such a rare book that only one copy is available for consultation. Article accomplished with the support of the PNAP-R Program at Fundação Biblioteca Nacional. Gigantic, infinite structures such as the Ocean or Cosmo, the History and the Myth remain equidistant, independent, although close. The density and complexity of these two forms hovering above the head of every human being, dead or alive, may suggest that it is a futile task to try and bring them together, or some imminent danger in the shock of both. But the ritual and fiction make this possible: Myth and History in a frame together, so that there are confluences, blends, collisions. The fierce and exquisite Avalon Brantley creations – Aornos, her new vision from the Greek Tragedy with Aristophanic irony as a design touch, the intrincated Descended Suns Resuscitate stories or the Fernando Pessoa tribute at the Dreams of Ourselves collection – at same time literature and ritual, detailed historiographical recovery and reconfiguration of personal mythologies, arises as a witness of the infinite, risky Myth and History Ars Combinatoria.

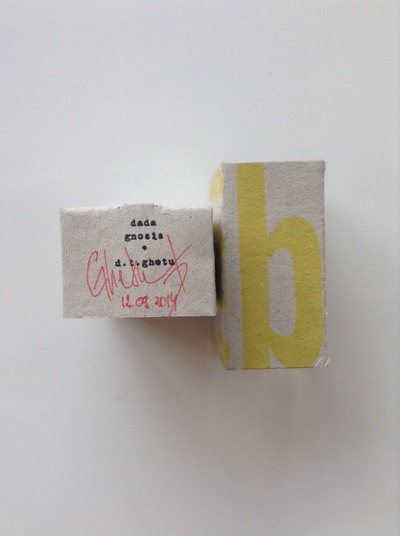

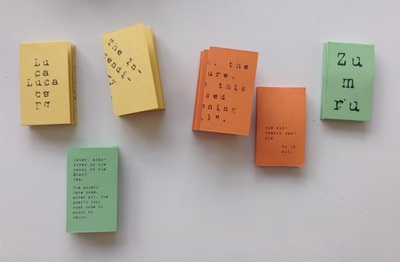

Your magnificent theater play – or perhaps narrative –, Aornos, has some resonance in Aristophanes The Frogs, something which is clear from the book epigraph (a quote from the great Greek comedy writer who serves as premonitory reference about your protagonist's name, Alektor), the theme of the descent to the dead underworld and the cicadas chorus that punctuates the plot as the chorus of frogs that accompanies the descent of Dionysus and Charon in The Frogs. Talk something about your refined work, a goldsmith labour, in the invocation of tragedy and comedy produced by Ancient Greeks. Well, I guess Aornos must be considered my first major publication, although it's by far not my first major composition. For me, however, it's definitely one of my most personally satisfying works. What surprises me about saying so is that I wrote the play in a week, when a story I had intended to include in what was meant to be my first major publication – the short story collection with Ex Occidente – instead was placed in another anthology. I wanted to fill this gap, but had nothing else I felt was fitting to include in that particular collection at the time, so I hurried through with my idea for Aornos. The seeds of that piece have in a vague way been at the back of my mind for years, though; I guess sometimes certain works mature in the mental cellars even more than their conceivers might realize until it's time to bring them to light. The Ancient Greek vision of the Underworld profoundly influenced Western literature and poetics, as well as many stages in Christian theology. For instance, there's nothing like it to be found in the Bible (Sheol and Gehenna are not the same as Hell) until the somewhat anomalous madness found in John's Revelations, and by then we're nearly a hundred years into the Christian era and referring to a book nearly discarded as apocrypha. So all the traditional visions of Hell used to terrorize sinners and Tantalise poets have tended to come at least in a greater part from pagan traditions. It's a large part of our literary heritage, and has fascinated me as a possible plane of creation for years; but I wanted to return to some of its cultural roots too, so I read a lot of comparative matter and siphoned through some out of the way materials both literary and academic, in order to work with some of the more gritty, obscure and forgotten aspects of Hades. Aristophanes is certainly a fascinating writer for me, in part because, despite that he is one of the earliest surviving satirists of the ancient world, he maintains deep reverence for certain sacred aspects of his own culture, such as the Eleusinian Mysteries (for which of course more modern critics were keen to criticize him). But in its place and context I actually find this quite a remarkable and endearing trait of his work and intention. As a student of history, I recognize exemples of unscrupulous and overly-imaginative writers whose works have hindered a reliable grasp of the past; yet, in the other hand, there are those who in a somewhat contra-rational way help to bring their readers into the key mindset of their time by this same wayward means, a context of the culture and its own dynamics and poetics, which dry history cannot do. Not only Aristophanes in this sense, but even moreso “historians” like Herodotus and Plutarch. I have very much enjoyed reading Thucydides (including his history of your namesake, Alcebiades) but his histories played no influential role in the construction of what is essentially, as I've described it elsewhere, a “mind-staged play”, a poetic rendering of the play structure perhaps, like (as you astutely pick up in your next question) Yeats' Purgatory. I did however find the history of Herodotus directly useful – for instance, the Bridge of Medea which Alektor strangely discovers in the midst of the waters whereon he has wandered comes straight from Herodotus. The point is that while Herodotus is one of our first “historians”, and Aristophanes one of our first “comedians” (at least in the sense of their subsequent influence; there were other, older writers of each kind) they both still help me to connect with a mindset long gone. I don't completely abjure the Age of Reason or Enlightenment as it were, but poetry and fantastic literature should demarcate a boundary beyond which the phantoms of so-called “reality” and reason grow misty and uncertain. The work of historians such as Thucydides or Gibbon will still be useful there too, but there the passive, intellectual process of reading for which these works were intended gives over to the dynamic, creative churnings of poetry and madness. At the final moments of Aornos – after the appearance of the extraordinary Stettix, a unique and fantastic character – becomes clear the early intuition that the reader may have noticed from the start of reading: your piece is practically non-representable. As in Ionesco Rhinoceros and Purgatory by William Butler Yeats, the scenery described in Aornos are better made by the imagination, the superior way to achieve the delicate and subtle games and images suggested by the words. Even the best set design built for a movie or a play would lose this suggestion effect. How you reached such imaginative and visionary synthesis? Is there any work that you face as a forerunner in this regard? As I couldn't help mentioning above, yes, the Imagination really is the ultimate theatre, or should be. In this age of movies chock-full of CGI, surround-sound effects, computer animation, hyper-realistic video games, all headed toward constant 3rd-party virtual reality, what I think is tragic is that part of our culture that is becoming so imaginatively lazy that it craves the crack rocks of spoon-fed media – immediate gratification of all the senses – from the outside! – which is powerful, yes, but it will allow the imagination we have brought with us since long before the dawn of literature, out of dreams and uncertainty at the vastness of this universe around us, to atrophy. So to answer your question, I would have to say that for me, the forerunner of this kind of imaginitive writing would have to be anything of a fantastic nature I read or had read to me as a child, when my undulled imagination played its part with alacrity, agility and brilliant vividness, so that I became so addicted to that aspect of reading and daydreaming that I craved it constantly. As an adult, in the empirical world, it does become progressively difficult; reading is harder work, like exercise becomes – you have to keep those muscles toned and joints limber. Not all written works readily lend themselves to this, but some will open up if approached in the right mindset, like a song you didn't care for at first but then begins to grow on you. For me, music is a very similar experience – there is an inexpressible magic in the fact that a series of patterned noises can cause entire worlds to explode into being behind closed eyes. Or just simply being in a place whose genius loci begins speaks to you, when certain special places can suddenly and inexplicably begin to whisper stories--images engendered in your head yet seemingly born straight out of stones and scents and sky. These things all have to come from the inside first, not some cinematographer's cutting room or programmer's code, but from inside the psyche itself. Or, if the opposite is true, one still has to keep the womb of Psyche ready to receive such transient gametes of inspiration. Both Aornos as the tales of Descended Suns Resuscitate worked an unusual cross between Myth, History, Daily Life and Fiction. In this sense, there is a thorough preoccupation with details, soon unfold in sophisticated language frames (the local argot, specific jargon, etc.) that evoke the past (even in their small detail everyday) while that assist in building complex narrative purposes: the irony and the mystery of the plot. What is the origin of their perception of these lines of contact between Myth and History? How to deal with the troubles related with this seemingly contradictory combination? But don't we live our lives in a seemingly contradictory universe? What perception is not at least in part a false perception, part of our contemporary mythologies? We still don't have a Grand Unified Theory of physics, and isn't there still so much that we have to admit on an epistemological and ontological basis is subjective? What fascinates me is how other cultures, without all our pintellectual taboos and inhibitions (or in this generation especially our technologized myopia), how those others might have interpreted the mystery that is being here, that is interacting with this powerful, cruel, incredible and mysterious universe. What I try to do (and perhaps it is a futile task from this vantage point (and yet poetically I don't believe that, even though intellectually I know that)) is to get into the mode of a character in a different time and place. At least, that's one of the aspects of my work that I'm most interested in concentrating on. Another time, place and culture, through the eyes that see within their belief systems, the way folk spoke, and how they lived their days, all these things would play a role in how phenomena are interpreted. These same limitations overhang us, as our children's children will all the better see, because we each can barely help interpreting the world through our own limitations and prejudices only, both personal and cultural. The reader must be somewhat out of place in the past, because just as L.P. Hartley said, “They do things differently there.” It is a different world than this. So I consider the past highly fertile ground for imaginative fiction. Also, poetically at least, I don't imagine time to be quite as strictly linear as we tend to perceive it here in our daily lives, keeping appointments and bedtimes. I try sometimes to mediate between (and amalgamate) our realities and the realities of somewhen else in a way that allows some inroad into the past but which also can maintain connections and perhaps strike sparks in the reader's frame of reference as well, a kind of literary deja-vu effect. Hence Alektor's response to the sudden apparition of Stettix arising before him out of the back of the boat is a line partly borrowed from the response of Lucifer when he encounters the monstrosity of Death in Milton's underworld. This for me again is poetic time going non-linear. Milton's words can come out of the mouth of a character set in Ancient Greece because they reached Milton's pen from out of a formless and timeless place whence the voice of his daemon (like a crouching toad perhaps?) hissed them into his ear. The Japanese writer Ueda Akinari in his book Tales of Moonlight and Rain – brilliantly adapted by the sensitive Kenji Mizoguchi in the movie Ugetsu Monogatari (1953) –, constantly works with deception, misleading cognitive perceptions that evolves from what we perceive as reality (which includes, of course, the supernatural). Many of your protagonists and characters hold this false perception of the universe around them. What would be your path to this poetic of deception, quite sophisticated in your narratives? The universe itself is a circular, loopy, tangled epic of unending deceptions. I guess my characters, just like us, have to gather up as many pieces of the puzzle as they can along the way, dropping some, mangling others, as they stagger toward whatever course on which they've set themselves. I wouldn't judge them all that much more deceived or mistaken than I (or may I venture, we?) must be, at least some of the way. Cognition, senses, perception – they are all just fallible approximative media anyway. But they're all we get so far, and despite the horrors, we sometimes catch glimpses of beauty here too. And then, when the horrors are beautiful...?! One of the Descended Suns Resuscitate tales that pleased me most was “The Last Sheaf”. In this plot there are many layers and paths: a curious and complex relationship between allegorical (peasants scything the crops, the conflicting notions of sacrifice and heroism), prosaic (a tourist trip of two students) and even caricatural or grotesque (the diary's pages, used to help in a serious case of diarrhea caused by the withdrawal of laudanum) purposes. The outcome brought to my mind the story “El Sur” (“The South”), the last of the Jorge Luis Borges collection Ficciones (1956). What procedures you employed in the construction of this (and other) tale(s)? Is there any usual method or each narrative has its own genesis and development? I think each narrative accumulates in its own way. Sometimes, as was the case with “The Last Sheaf”, a story will emerge directly from certain materials I am reading, sometimes while my eyes are on the page, sometimes after the book is closed, lights are out and eyes are closed... other stories seem to appear spontaneously from staring out of a window, listening to a song, visiting a new place.... There are constant fragments of stories, everywhere – in the ruins of an old house across a field that likely enough was once some long-departed somebody's dream home; in the faces of strangers walking past, or laughing or talking or seated in thought; in old clothes or photos, or objects in second-hand shops. Listening to these lurking stories is both an active/creative and (strangely) something of a passive process. It is work to craft a decisive cohesion to what are often only vague snatches or ideas, but in that process the strongest ideas sometimes begin to mature and develop somewhat on their own. Your stories discuss some civilization decline significant aspects: the apocalypses scales from the small to large ones, snapshots of decadence and exhaustion, voluntary and compulsory sacrifices. Two obvious examples in this sense: “The Way of Flames” and “Kali Yuga: This Dark and Present Age” in Descended Suns Resuscitate. So, perhaps it may be possible to say that your vision approaching that of James Joyce in Ulysses, about history as “a nightmare from Which I am trying to awake”. The decadence, in your narratives, was fed by philosophical reflections? Or your concern lies more significantly in the aesthetic field? Both in perhaps roughly equal measure, depending on the context. I have always been fascinated by the terrifying cyclicity of existence, of history, of human nature. The things we take for granted in developed countries are very fragile and have not tended to be the norm in most times and places. The preoccupations of decadent literature thus seem consistently à propos, and I expect will continue to be so recognized in an intermittent way, as the pendulum of history continues its wayward swaying... The music occupies, more obviously, a major space in the Aornos and the story “Hognissaga” narrative construction (although the same can be said of almost all your tales, since the musicality expands itself to the language’s core). What is your relationship with music in terms of your narrative building strategies? Is there any composer or style that is most suggestive in this regard? Again, it depends on the context (since each story develops in its own separate way) but there are times when music is the primary cofactor in the catalytic process by which a story develops itself. At other times, music might inject its own influences and ideas in ways I could never have predicted. I am extremely eclectic and enjoy a wide variety of musical styles, as well as recognize times when certain songs or styles I might generally find repugnant can in their own ironic way lend me helpful inspiration or insight. Considering that you published a dramatic narrative and short stories, it would be possible to forecast some of your future projects? Are you working on a more extensive narrative or even some visual and/or audiovisual creation, with all the powerful visionary inventiveness which is so remarkable in your stories? I have worked on a number of things which are at the moment unpublished, some of which may never be released for personal reasons (not all the writing I do is meant for publication; sometimes it just has to be done) and others I have yet to find a home. I tend to be remiss about submissions – it's my least favourite part of the entire process. I have written a full-length novel, a sort of triptychal response to William Hope Hodgson's House on the Borderland and his The Night Land. I also have both ideas and rudiments for several other projects, but right now I am working on something of a short novel, a very strange wide-ranging piece, set in different times and regions of Russia, though predominantly in the late 1930s during Stalin's Great Purge. When I have finally finished that piece (and I have no idea at the moment when exactly to expect that) there are several other areas I hope to begin to work in, probably as thematic short collections – one involving the Celtic peoples of the British Isles (a subject and setting with which I have already spent some time with the writing of my Hodgson homage), and another set in Colonial New England. Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). There are few known examples of literary works that use divination systems as a essential structure form in narrative or poetic terms. This is the case of Italo Calvino The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973), created from possible interpretations of the card sequences that illustrate each story – some of which appeared initially in an Franco Maria Ricci edition with splendid reproductions of a painted tarot deck designed by Bonifacio Bembo at the fifteenth century for the Milanese dukes. Another example: The Man in the High Castle (1962), the Philip K. Dick alternate reality novel, in which the I Ching, the classical Chinese oracular text not only appears as a narrative device but as a resource for imbroglios solution with the story employed by the author. More rare, however, are the cases in which a narrative or poetic work becomes itself an oracle, absorbing the suggestive properties of divinatory arts texts, images and symbols. This is the Los San Signos case, a kind of imagetic/interpretative translation of I Ching by the Argentine polygraph Xul Solar, into a new language – invented by the author – the Neocriollo, colored by images taken from sources such as Dante's Divine Comedy. This is also the case of Dada Gnosis, a work by the Romanian editor and writer Dan T. Ghetu, whose oracular resonance was perceived by another extraordinary author, Damian Murphy, in a review at Internet (another excellent review/experiment, a review without words, was photographed by Des Lewis).

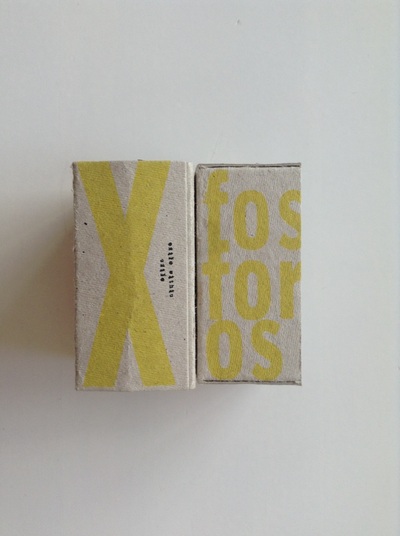

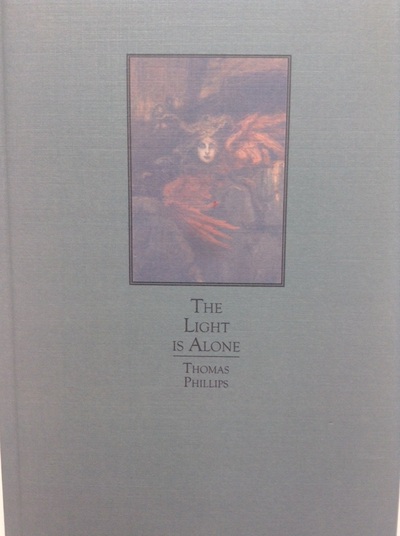

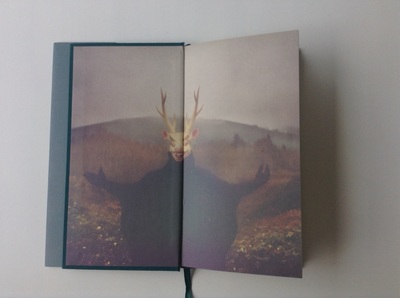

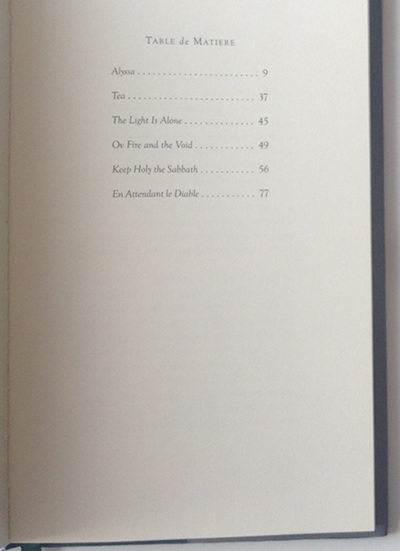

Speaking about the physical format, as a object, Dada Gnosis is not even similar to a book, because it is a box of matches littered with papers without any apparent order – in fact, there are six folded colored folios, a vague set of mini-booklets. This curiously shape refers simultaneously to a stranger tarot deck and an very appropriate scheme to the illegal texts dissemination, as papers neatly folded and hidden in unsuspected places. Each of these booklets contain poems that reference poets victimized by the terrible historical storms that harassing Romania in the twentieth century. As the title suggests, we are facing a kind of contemporary and iconoclastic gnosis, the knowledge by the power of chance and negativity, both pulsing from every one of the Ghetu poems. These vertiginous and short texts in poetic prose approach themes like the exile, loneliness, war, isolation, persecution. The Ghetu poets join the Jews in the cosmos of persecuted minority, a direct understanding of the people's fate, without any place where they can rest for a long time, before resuming his exile, his escape or death. Thus, the predictions evoked by this curious oracle are not like horoscopes designed in mass media tabloids: the possibilities are protruding from the ruins, a inescapable trend exemplified by the History, the background of each of the hexagrams of this new I Ching. Indeed, there is something ironic and enigmatic in conceiving reflections of frantic and titanic historical conflicts in small folded texts, stuffed inside a small box. These two attributes – the irony and the enigma – attached Ghetu, an editor with immense talent in his Ex Occidente Press, a legitimate heir of the Romanian avant-garde group, the Bucharest surrealists of “Infra-Noir”, who worshiped the mystery, the secrecy, the myth renovated as a strange form of revolution needed to subvert/destroy both the far right politics as the authoritarian left control, both joined by the same prejudices, the same hatred of freedom, in the same false and ridiculous mythology cult. In the Ghetu’s poem dedicated to Mehmet Niyazi, there is a very significative verse: “The angels have come, after all. The poet’s long road home is about to begin.” In the sorrow of the exile, escape, persecution, death, the poem designs the configuration of an open road, a road movie without end. The oracular happiness in Dada Gnosis emerges not from false hope or trivial everyday unreality, but from the poetic perception of a world steeped in blood, but still open, a possibility, a chance. The embodiment of terror in the mind and the perception structures, unstable, a perpetual spin, beginning and ending in cycles that could be endless. The devil, not as a folkloric, horned figure, but as a feasible existential possibility, a everyday chance, although not at all trivial. The horror story as an experiment, an outburst, musical harmony, as a new roman by Jean Ricardou or Alain Robbe-Grillet. That's all about the collections of short stories The Light is Alone and Malingerer, wide fields of audiovisual findings, diabolical presences, complex and unspeakable constructions. The author, Thomas Phillips – writer, composer, theorist – whose interview follows below.

A interesting element in your narratives is the ritual, the stylized way of life used by the characters in their interactions. Of course, some plots directly address the ritual – "Alyssa", "Keep the Holy of Sabbath", "The Evil Thereof", "Hideous Gnosis" – but in all his tales of the books The Light is Alone and Malingerer, the reality is constantly ritualized by characters, so can (or imagine) get a complex interaction with the universe around them, that is, the ritual is like a process of our nature, as meaning that we commonly use down in a universe of random repetitions and little sense. This conception of ritual emerged from some reading/theoretical interpretation or developed as a narrative construction aftermath? This is a fascinating observation, particularly in so far as I tend not think of ritual as constituting defining moments in the stories. Rather, it is more aligned with formulas that emerge from the milieu of the story itself. Satanists engage in ritual, as do fundamentalist Christians and black metal musicians; it appears in my work, then, as a kind of prop, as opposed to a theoretically-informed anchor. This is not to diminish the general significance of ritual in everyday (or exceptional) life, though I'm mostly interested in literary style and form over such content. I realize in reading your stories, a complex approach to spatial displacement: places that lose their usual concreteness (the dentist's office in "Ground Drilling" or the beach in "Ov Fire and the Void") or characters that become, in a way or another, exiles, expatriates, individuals who are forced to displacement by external, unmanageable forces. This spatial issue arose by personal experiences? How did you get this approach to the exile, the instability of the usual space? I've spent significant periods of my life living abroad, in Finland and Quebec, in addition to casual traveling. Though these experiences have been largely positive and formative of what is perhaps an idiosyncratic literary sensibility, at least in the context of American fiction, they have certainly provided a taste of displacement or dislocation that is inevitably as challenging as it is productive. One can go a certain distance in determining the quality of one’s interiority, in controlling one's reactivity, but the external forces you mention may be especially robust when acting on us in relatively unfamiliar contexts, which of course is an excellent reason to live abroad, to abandon, however temporarily, what is safe and comfortable. From a theoretical perspective, I've always been keen on Viktor Shklovsky's notion of literary defamiliarization, of removing an idea, a character, or an object from a familiar context and placing it elsewhere so as to produce a novel perspective. I suppose this is what we do with ourselves when leaving habitual terrain, be it geographical or psychological. Some of your stories deal with the baffle interpretations by humanities and social sciences at our time, by the use of exquisite and sophisticated irony. Philosophy, semiotics, anthropology and some analytical social conceptions arise especially in Malingerer (I think the first tale and "Hideous Gnosis” as good examples). His interest in these disciplines is related to research or emerged as a form of ironic treatment of excessive systematization of our perceptual reality, a veritable trap of all our systems of meaning? I was introduced to post-structuralist and postmodernist theory as a young literary student and was immediately captivated by its resonance with certain religious or mystical ideas that had come to inform my sense of humanity's severe limitations as well as its prospects of more or less transcending the latter. Theory can doubtless be excessive in so far as it operates as yet another mere institution, a doctrine that ultimately elevates the ego, particularly one in process of chasing an academic career, though it also has much to teach us regarding said limitations and, in a few cases (Deleuze comes to mind), techniques of unblocking ourselves, of stripping away the paint of normative ideology and hegemony. With horror fiction, I tend to be most concerned with exposing impediments and blockages, particularly those that arise from rather gruesome power structures. Of course, I’m also interested in the presentation of unsettling atmospheres, creepy, confrontational ambiance. In my opinion, the element that makes the HP Lovecraft's fiction extraordinary is the systematic use of synesthesia for narrative construction – the monsters, the scenes, a whole world emerges from evocations based at the crossroads of senses associations. I think your stories have, accordingly, certain resemblance to the Lovecraft work: in them, there is also the systematic use of synesthesia. Although the central element of perception in your plots seem to be aural because the characters construct and deconstruct scenes and moments using auditory perception, by the sounds that evoke images, colors and movements. What strategies do you use to build this universe of indirect perception? How you work out the synesthesia and the aural assault, in preparing your fictions? I must confess that I don't evoke a particular strategy in this regard. That said, music/sound/listening have always been important in my life, so it's no surprise that they emerge periodically in the writing. Another way of addressing this issue is, as the question suggests, to reference other writers. Lovecraft is certainly an influence. I think, too, of Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House and the manner in which the house manifests its anthropomorphism via sound, how it affects the senses with relative nuance. Perhaps we could even speak of a synesthesia of influence, of how particular words and tones, their signification, provoke related but divergent responses in a reader/writer. Your production is multifaceted, wide: there are essays, novels, short stories, musical compositions. Theory, narrative, music. On the other hand, their narratives reveal a close co-existence of all these elements, especially by synesthesia and ritualization (in the case of the theoretics). How the narratives came under your creative possibilities? Emerged as a result, simultaneously or preceded other activities? As it happens, my initial forays into creative writing, as a young teenager, explored the horror genre. Jackson, Lovecraft and Clive Barker were my primary guides. It was only later, in my twenties, and following committed, university literary studies, that I began writing novels prompted by the "synesthesia" of reading different writers – Kundera, Duras, Hesse, Baldwin – a peculiar assortment. By the time I discovered contemporary French writers associated with publishing houses such as Éditions de Minuit and P.O.L., I recognized a literary voice, or voices, that I had to make my own. Writing has been a staple throughout my life. The same can be said for music as well; as a listener and practitioner, I've never been without it. Inevitably, the disciplines (and they certainly require discipline) inform one another, which speaks again to your observation about the role of sound in my stories. While my novels tend to focus on the psychology of the quotidian, with few of the trappings of more conventional fiction, horror is a unique pleasure for me because it relies on provocation of the senses. Though my horror fiction isn't especially conventional, relying, like the novels, as it does on a minimalist aesthetic, the genre requires tension born of atmosphere, (in my case) a modicum of but a charged and immediate mode of description. If the novels are akin to a minimal, delicate music composition, the horror stories, though still reduced, are more aligned with a short blast of harder, heavier music. Theory, of course, is yet another writing mode that offers its own pleasures, and like other genres, is one that is always evolving in my practice. How to maintain a level of stylistic ingenuity, to balance this with clarity, and still operate within the confines of certain academic formulas – this is an ongoing effort for me. The infernal power is a recurring element of the tales of The Light is Alone and Malingerer, although the evocation – so to speak – of the demonic being is never straightforward. Your devil is a possibility, a suggestion, a peculiar form of Nature not bend to human plans – even in the case of some soi disant adepts. The demoniacal force comes suddenly, an inadvertent event even for those who are waiting eagerly (as in the short story "En Attendant le Diable"), a possibility impossible to frame in traditional tables of philosophy, history, theology. How did you come to this original narrative perception of evil? What, in this sense, your main influences? There are two central points of origin here. First, I enjoy horror that examines not simply the figure of Satan, which of course I regard as nothing more than a myth, but human – all too human – practitioners of Satanism, people who are inevitably flawed, damaged, or simply over-invested in the ego and yet, as a result of their suffering, manifest exceptional power in the context of quite ordinary, bourgeois society. Such characters make for fascinating narrative constructs in so far as they speak to a general dis-empowerment in the everyday and our collective yearning for agency. And naturally, as with any fictional form, the uneasiness that almost invariably results from efforts to advance tipping over into raw egotism is tremendously seductive. Like most readers, I receive a kind of perverse pleasure from the violence of witnessing people rise and fall. Which is not to say that I'm in any way misanthropic or particularly negative. Consider the incredible tension in the children's stories of Dr. Seuss or Charles Schulz. On the other hand, there are real dangers in the world, all of which, I believe, can be understood from the perspective of unconscious, reactionary modes of being. Terry Eagleton makes the point that reactionaries, in the form of religious and political fundamentalists, those of us who haven't the self-respect or motivation to think critically and intellectually about what it means to be a self among others, are weighted down by a surfeit of being, a crystallized or monolithic identity, as opposed to the non-being that allows, and indeed, compels one to embrace a more fluid and open existence, which, of course, is the nature of our collective experience, try as we may to impose embarrassingly absurd and paranoid boundaries around ourselves. This condition signifies true evil to me – unconsciousness – the face of Satan that is far more frightening than any horned figure. Hence a Tea Party Rally as Black Mass in the story "Tea,” or an evangelical school teacher whose patriarchal neurosis around sexuality, Biblical literalism, and a particularly American work ethic finally summons a rather vicious demon. The structure in the tales of The Light is Alone and Malingerer seems to favor the narrative as a short form – even though there is the suggestion that the tales of the two books have resonances, closeness, including by this curious sequel relationship between "Alyssa" and “Malingerer (is That you, Alyssa?)". The decentralized, fragmented construction with incessant new beginnings that we see in your tales benefited the choice for short narratives, these diabolic tales? Have you any plans to expand these tales in a much longer narrative someday? Despite the gravity of my response to the above question, horror is first and foremost a source of joy for me as a writer. I love reading it, watching it. As such, the short story format is perfectly suited to my ambitions in terms of occupying relatively short bursts of writing that may be, ironically, even more experimental than my novels to the extent that I give myself the freedom to do anything with the former – as long as it communicates a sense of darkness. So at the moment, I don't have any concrete plans to write a horror novel, though it isn't outside the realm of possibility. I've just finished the first draft of an academic book on liminal narrative that addresses horror in a longer form and, I must say, this experience was delightful. So perhaps I will turn that theoretical lens toward an extended burst of fiction at some point. The question makes me think of T.E.D. Klein's wonderful story, "The Events at Poroth Farm" and how I remain anxious about tackling the related novel, The Ceremonies. I suspect this is my loss. Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN). If there is something that makes the narrative something close to a witchery, a gesture that belongs less to the human and more to fields related to the supernatural sphere, the metaphysics speculations and fears, is the Mystery. And there are a kind of Mystery overflow in Jonathan Wood stories, as in the participation that he made at the volume in honor of Fernando Pessoa, Dreams of Ourselves, released recently by Ex Occidente/Zagava Press. This is a a fundamental and transcendent Mystery that disrupts the very reality, not just our usual perception of reality. In the following interview, we propose not to deciphering the mystery, vain and destructive activity, but to contextualize the Jonathan Wood fascinating creative mind.