|

For the extremely active Jesuit Athanasius Kircher – collector of the exotic itens from the Past, Egyptian hieroglyphs peculiar descrambler, prodigious instruments designer – the play of light and shadow that simulates the movement and the life, that trick or effect that one day will be called Cinema, was very more than a base trick to deceive the senses. It was, rather, a peculiar way to interact with reality: something that was called at that time magic – the ways to access the positive or negative forms of Wonder and Nature. In the Dutch city of The Hague, not far from the home of Father Kircher in Rome, Christian Huygens, a notable Scientist in the fields of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy created a new way to project skeletons and ghosts in animated sequences – an exciting new game room with lights and images made by light. Both, Kircher and Huygens, were opponents located at the points of the sphere of knowledge ranging from Science to Quackery. Even so, in the case of the invention whose paternity is attributed to both, the magic lantern, the path traversed by either are the evil, death, and grotesque way, a possible uncontrollable route. The emblems of Kircher becomes dance of death in Huygens, imagination and Science conceptualization converge in grotesque images. This union of paradoxical facets, however complementary in some way, building a wonderful, technological, worthless and evil instrument emerges as central leitmotif of the new book by DP Watt, The Phantasmagorical Imperative & Other Fabrications. In this extraordinary book, each narrative emerges marked by tension between the prodigious and terrible, between the simple beauty of the obsolete/rare object and apocalyptic imagerie, between the elegiac evocation and ironic red smile, often soaked with blood.

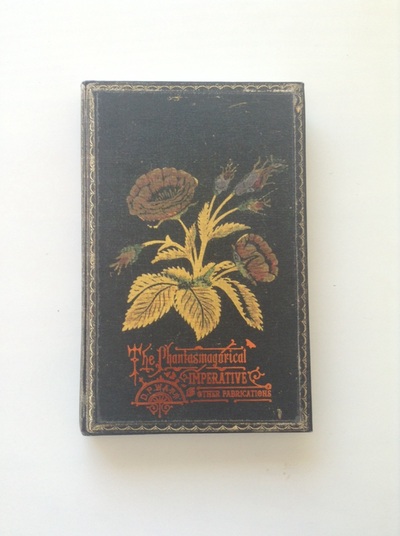

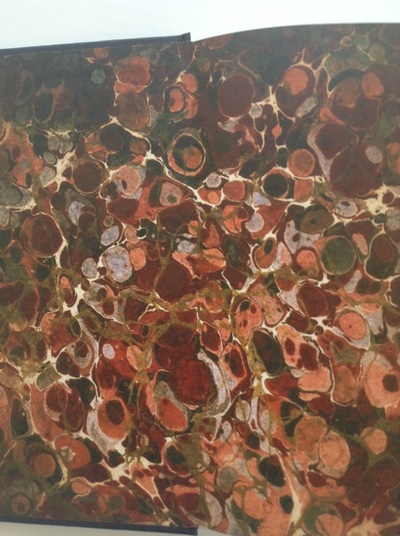

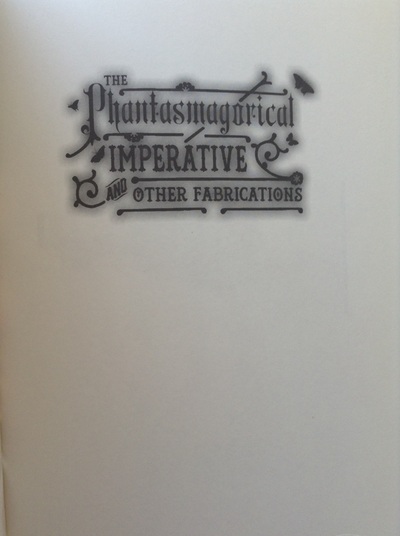

The D. P. Watt fiction is a new life form for an old insight that struck Heraclitus of Ephesus, for example: the awareness that there is a terror and a latent horror in the flow of dead objects that we believe are our objects and tools. Endlessly unable to break the chain of continuous metamorphoses, we suffered with the definitive loss of a solid identity that we believed so sound just a minute ago. So, the narratives that we find in The Phantasmagorical Imperative, superficially, could be seen as the collection of a beautiful and elaborate cabinet of curiosities. We have prestidigitation and metamorphosis, inanimate objects that come to life and vice versa, heavenly music from infernal instruments, photographic effects, and audio-visual transitions, faery landscapes from dreams and nightmares. But all this wild parade is just opening to the Watt real entertainment. These short stories protagonists – usually both witnesses, victims, executioners –, outsiders who have something moving: dissatisfied with the limitations of life, they found in some objects, instruments, miniatures and mirages new possibilities, perhaps what seems to be the only solution to the tedious cyclic continuum of the existence. Indeed, these objects these objects go far beyond the everyday, but not in the way our protagonists thought and this ironic solution summarizes the phantasmagorical imperative. Eugene Thacker mentioned in the afterword of the book, the Kantian notion of categorical imperative: the notion that we must act only according to a maxim which formulation is such that we want it to become Universal Law. That is an awesome and eerie resonance, a game of make-believe which aims to apply to the Ethics reign the made of steel invariable/intolerable and universal laws like those of Mathematics. Watt constantly reproduces the ambitious Kantian formula with some distressed and sinister results. The book The Phantasmagorical Imperative is a beautiful and fascinating object. The Egaeus Press exquisite edition evokes a refined object, although worn by use, found in the corner of an antiquarian. This effect is caused by the clever use of contemporary print reproduction technologies applied to a simulacra of the corrosive effects of time, an illusory game that anticipates those we see in the Watts plots: for example, there re, at the cover composition, the dimmed and toxic taste of obsolescence (the flower image, the typography), and the same happens with pagination and layout. The images reproduced in the edition are found objects, in the best Surrealist tradition, apparently torn photos and graphics (belonging to other books? Found on the street or anywhere else? Edited in software to look old and torn?). The history of this imagerie are truncated and finds a kind of mirror in the narratives – more than occasional illustrations, but comments linking the stories to fortuity, the usual way of mutation. The path that Mr. Watt chose to follow in his ferocious stories, to the endless reader delight.

0 Comments

The Egaeus Press creator, writer, editor, Mark Beech would first be remembered as the publisher of the cult small literary zine Psychotrope at 1990s. Nowadays, with Egaeus Press, his vision is "moved by the concept of the world as a haunted house, and by the paradox of all life’s darkest fears and most ecstatic wonders being essentially one and the same.” (from the Egaeus Press website).

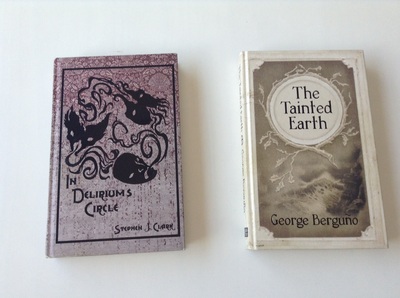

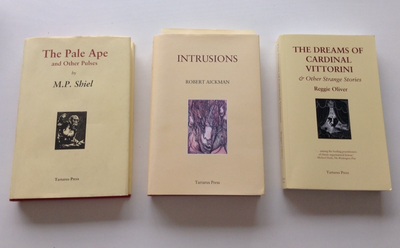

Although Egaeus Press is a young publish house, the first three book releases demonstrate breath and reasonably ambitious project. Could you tell a little more about the history of Egaeus? Perhaps the biggest considerations when starting Egaeus Press was wanting to stand out from other publishers. I wanted to hit the indie publishing scene fully formed and to make Egaeus Press books look and feel different from anything else that was out there - which was a little over-ambitious to be honest. From a business and design point of view, there are things I could have done better in those first months; and things I couldn't possibly have known without trying. But the books came out pretty well all in all, and I think I managed to stand out. I was of course very lucky to have Reggie Oliver, Stephen J. Clark and George Berguno for those first books. My own (very rare) writings had appeared in (quite obscure) anthologies alongside all three – although we had never communicated – which I think gave me the courage to get in touch with them, though I'm not sure it was much of a factor in their acceptance of my proposal. I explained what I hoped to achieve with the look and feel of Egaeus Press books, and I'm very pleased they trusted me. One of the most notable features of the Egaeus Press editions is it's the book design: illustrations, art, typography and book form mixed up in a rare harmony in a incredible way that the hardcover books seem lightweight and portable as paperbacks. What are the references for this exquisite graphic work? Some publisher in past as a influence? The only unifying factor in the design of Egaeus Press books is the impression of age; not necessarily of great antiquity, but of some other time. This isn't done through pastiche – and I don't think any Egaeus publication could be mistaken for an older book – but by using unfashionable design conventions and very simple things like header pagination and endpapers. I hope it works, in some intangible way on the reader – a hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck thing. I'm not sure I can name many publishers specifically as influential in the design of the book. I love old Edwardian children's novels and annuals because they are so over-designed, gaudy even. But evocative. Quality adult books of the era are often more austere, though there are some nice art nouveaux designs. No doubt these sort of books were not taken too seriously – likewise Victorian pulps are beautifully evocative. But just the dirt, the fade, and the library stamps in old books unintentionally add something evocative for me. With the design of Egaeus Press books I attempt to capture what elements of these sorts of designs and glitches work in a spine-tingling sense. Some publishers have a unifying vision or even a principle, a theoretical formulation that serves as some kind of guideline. There would be something similar in the case of Egaeus Press? It would be possible to define your editorial house with an idea, a word, a speculative notion? "Morbid and Fantastical Works" as the Egaeus Press subtitle says pretty much covers it. I don't like to spend too much time saying what I do and don't like to publish, because I too often these days come across writing which surprises me by defying its own limitations. There is a list of things on the website which it says Egaeus Press likes... including stuff like 'Clocks and clockwork', 'Crumbling ancestral homes' and 'The folk tales of Europe', but I was careful not to include what I don't like. As long as something 'feels' like it belongs to the kind of world Egaeus Press inhabits, then that's probably enough. Were there plans to expand the Egaeus Press catalog to other traditions of the fantastic: perhaps old authors or translations? If there is something, what would the authors that could be translated or published? The hardest thing is finding the time to expand Egaeus Press into areas I'd like to explore. At present I have enough going on to take me into the latter part of 2014, and ideas for projects beyond that. Another thing is that I like to be able to run ideas for the design of the books past the writers and make sure they have some input. It's become a very important part of what I'm doing. The books should have a little of the writer in them. To publish / republish / translate older books, perhaps by dead writers would require a different approach to the design. It's do-able, but it'd take some serious thought. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. In the Ex Occidente Press – a publish house with some works by D. P. Watt in its catalogue – web site, unfortunately nowadays deactivated, we found a small, but subtle and intriguing description about the author: “D.P. Watt is a writer living in the bowels of England. He balances his time between lecturing in drama and devising new ‘creative recipes’, ‘illegal’ and ‘heretical’ methods to resurrect a world of awful literary wonder. Recent appearances with Ex Occidente Press include his collection, An Emporium of Automata, in 2010, and tales in both Cinnabar’s Gnosis and The Master in Café Morphine. His first fiction collection, Pieces for Puppets and Other Cadavers (InkerMen Press) was first published in 2006 and reprinted in 2010.” The Watt’s fiction, in which the usual or unusual object appears as an element of amazement and uncanny, is very close to the heretical and illegal, in fact. The first steps in this unsound but fascinating universe can be followed at his Interlude House.

Your fiction (I take as an example your The Ten Dictates of Alfred Tesseller, a wonderful novella full of transformations), has an ingenious structure, in which there are moments when the reality seems stable with moments of full transfiguration – that's the best word I can find for your fiction effect –, with several elements of that reality changed in new and complex forms. This process/mechanism is the narrative itself, in same way. Surrealism seems to be the initial reference, but not the only one. There is a shift to the free form narrative, more freer than what we see in some cyclical narratives like in Alain Robbe-Grillet, but your narrative reserves a clear plan, far from cut ups or free association that we found in William S. Burroughs. Could you comment a little bit about this process of composition and the references that uses in it? It is difficult to comment on Tesseller, as this novella is a very particular case. There I was attempting to experiment with different perspectives of narrative from a position of flux. The being narrating it is engaged with the reader directly, claiming to have known them in youth, but also they are our connection to Tesseller, himself a consciousness in flight, beyond the grave. Each section is driven by its attempt to create that sense of another transformation without losing the overall coherence of the plot around Tesseller. In parts it succeeds, in others it becomes a little mired in some of the more poetic aspects I was trying to introduce. The transformation of reality is important to me, yes, but this comes, in many ways, more from the theatre than it does from literature. The process of composition changes with each story, and I have no particular allegiance to any movement, nor indeed anything as well-formed as a technique that I can deploy. My writing seems now to be more driven by scenes that emerge as I am working. Sometimes these can develop relatively coherently and chronologically, at other points they are very separate and can take many months to piece together, sometimes even swapping over from one story to another. I mentioned in the previous question, the terms "ingenious structure" and "mechanism" and, in certain way, your fiction seems fascinated by these elements. But it seems to me that your focus is not gigantic engineering works, openly devouring humans (which we see in certain fiction of the 1970s, as the mobile city in the novel The Inverted World by Christopher Priest or the highway infernal maze in J. G. Ballard's Concrete Island), but the works with subtle engineering, the smaller scale employed to deceive the perception postulated by everyday reality: the effects of prestidigitation, the cinematographer, the praxinoscope, automata, ventriloquist puppets, etc. What would be the source of this fascination? Yes, this is right. I am not that interested in timeless monsters from the nether regions of space or zombie apocalypses—although they can be fun. I find there are far too many monsters and apocalyptic tendencies within each of us. I am interested in how the ‘everyday reality’ you mention and those smaller moments contribute to a larger effect though. The strange, weird, supernatural, whatever you would like to call it, is happening all around us. Not as a manifestation of something, or somewhere, else, but rather as an example of our own otherness; those hidden and devious methods through which we manipulate, control, hurt and subjugate others. Puppets, vent dummies, magic tricks etc. are means by which to explore self-deception through that sliding, fading, or failing perception of the world. As I mentioned above it is the world of performance that has influenced me more than anything—Strindberg’s Dream Play, Jarry’s Ubu Roi, Gordon Craig’s uber-marionette and Kantor’s bio-object. In the puppet theatre and the carnival, or fairground, we find an alternate reality that seeks so hard to entertain through showmanship; just by twisting the performative slightly one can distort the real and explore our relationship to those things that we seem to find so fascinating and frightening; sex, death and nostalgia (or dreams). That all sounds very grand. It is not meant to be—quite the opposite in fact. It is from these minor, devalued things, slight experiences, supposedly unimportant ‘entertaining’ events, that I think fiction can comment upon the world with humour—by disrupting the real, playfully and experimentally. In this sense, the cinema seems to occupy an interesting place: the moving picture appears to broaden the infinite possibilities of deception and this is replicated in your fiction. I have in mind, in this regard, especially your short story "Dr. Dapertutto's Saturnalia". This impression has some basis? In this sense, what author or cinema style often useful as your inspiration? I’m intrigued there by your use of the word deception in relation to cinema. It seems to me that writing is also manipulative and it must be aware of the timeframe it operates in just as much as cinema. This is what interests me most about the relationship between author and reader. As much as you may work at the pace of writing it cannot deliver this in the same manner as a work for the screen. Pace might be manipulated in minor ways, perspectives shift back and forth, but it requires more control and patience to generate something that is not simply a confused wreck. Film can, as in many ways the theatre can too, always rely upon its visual aspects to further control meaning and, as you say, “deceive". Where lengthy descriptive elements in fiction intervene they can be either revelatory or calamitous, by that I mean unnecessarily disruptive, especially in short fiction. The form of film work that most interests me is animation, especially the works of makers such as Starewicz, Barta, Svankmajer, Norstein and the Quays. Its artifice is obvious, its materials frequently poor; rubbish, broken wood, discarded toys, rusted metals, meat, dust and dirt. From this they elaborate magical transformations through a painfully slow process. Charles Patin, in his letters to the Duke of Brunswick, describes a magic lantern show, patenting the famous phrase "l'art trompeur" to characterize this strange spectacle in which convergent images "rolling about in the darkness". That expression reminds me quite your fiction, in which visual and descriptive elements seems essential as structuring the plot, however these visual artifacts soon proves fallacious. How about the relationship between visual, descriptive and literal elements in your narratives? You use some visual procedure (image or object found, for example) in preparation? Often the writing starts from a particular object, or image. At the moment I am very interested in cartes-de-visite and have just completed a story, "By Nature’s Power Enshrined", based upon a chance find of a particular card. The staged environment of the early photographic studio fascinates me. The patience to produce something quite akin to a painting, and the careful balance of components that give meaning, such as the backdrops, the props etc. Now that we merrily snap away every second of our lives and then distribute the images widely to those we know neither well, nor closely, seems to lose some of the care of the staged image. I suppose a scene in a story also goes through processes of ‘rolling about in the darkness’, both in the mind of the writer and the reader. Its coming to clarity is not guaranteed on either side. If it survives as an image that intrigues and provokes thought, much as the magic lantern, then that may well be enough. There is certainly nothing as elaborate, or controlled, as a procedure. Sometimes an object, or image, may be too close or too known, and that can be difficult to work with. I prefer things that call a little to be reworked, or explored, through a piece of writing. One of his last works, published by Egaeus Press, was this narrative piece about the transfiguration of the Mr. Punch, this strange and curious theatrical plot on violence and crime for children. In fact, it seems to me that your fictional universe is very close to the spirit of this ancient popular work. Your approach to the ancient sources is often more intuitively, transforming them into symbols, or you prefer an approach based on historical research and some archeology? Yes, Mr Punch is close to me, as are all puppets, but there is something especially enduring about the way that Punch has travelled, popping up in his various guises around the place. His violence speaks of the drive to become oneself, at the expense of other selves, and maybe some of my stories explore that tension between an ethical compulsion to eradicate self and the relentless urge to make one’s presence known to the world. Certainly there is historical research, but again this occurs rather chaotically and I attempt rather to draw out, maybe ‘intuitively’, maybe through ‘symbols’, those aspects of a particular historical incident, life, or span of culture, that—through fiction—might be seen to be grotesque versions of our reality. Are there any plans in adapting your work for the cinema or another audiovisual, theatrical or multimedia expression? There are no current plans for adaptations of my work in any format. Well, nobody has approached me about it anyway! I would enjoy seeing some short films of stories, especially those that might evoke some of the strangeness of objects that has always fascinated me. As a final question, it would be interesting to know the authors, past and present, that you admire or consider important for the construction of your narrative style. When I began writing prose I attempted something along the lines of Beckettian narratives, but without any of the skill to extract and edit to the point of absolute purity of expression. At the point that I relaxed and no longer attempted to emulate the works of those I admired I think I began to enjoy reading again—when it was no longer about learning, but appreciating the work for what it did, rather than how I might attempt to deploy it. Given that, I wouldn’t know where to start in charting what might be important in how my narrative style has developed from other authors. Perhaps it is enough simply to cite some of those authors whose work has particularly struck me. My main interests focus upon European writers, particularly E.T.A. Hoffmann, Maurice Blanchot, Stefan Grabinski, Franz Kafka and Bruno Schulz. My interest in “weird" writers is fairly predictable, including Arthur Machen, Robert Aickman, Sarban and M. John Harrison. There are so many contemporary writers whose work I have been enjoying, including Michael Cisco, Jonathan Wood and Derek John’s work in particular. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. Currently, the statement that the artistic avant-garde of the early twentieth century expanded the space and freedom of artistic inventions is almost a platitude. In this sense, the new possibilities and paths opened up by modernity in the Art also reached the narrative construction: after the realism developed throughout the nineteenth century achieve an amazing level of plot detail, even with the mimetic reproduction of nuances and peculiarities in perception, time, space, the modernity surpassed the need for systematic reproduction of the moment, the usual possibilities provided by common layers in everyday. Such creators have rediscovered the form of the plot without the myth of psychological, social and historical “need for depth", emphasizing repetition, ritualization, false paradoxes, erasure. In a word, returned in Space and Time for the powerful energies of myth, fairy tale, the legend, the supernatural. In this sense, the avant-garde artistic movements in the early twentieth century sought a curious ascendency, strains of certain antiquity, points of contact, missing links - a thriving and turbulent universe of narratives and representations was recovered within the huge and febrile, contradictory and conflicting tableau of aesthetic avant-gardist conceptions. It is in this complex context of rediscovery and conflict about this new territories we found the work of Roger Caillois (1913-1978).

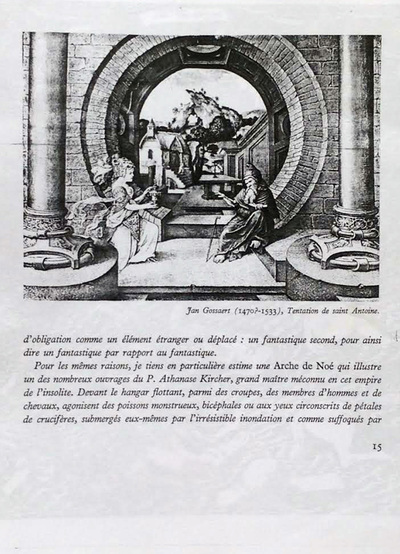

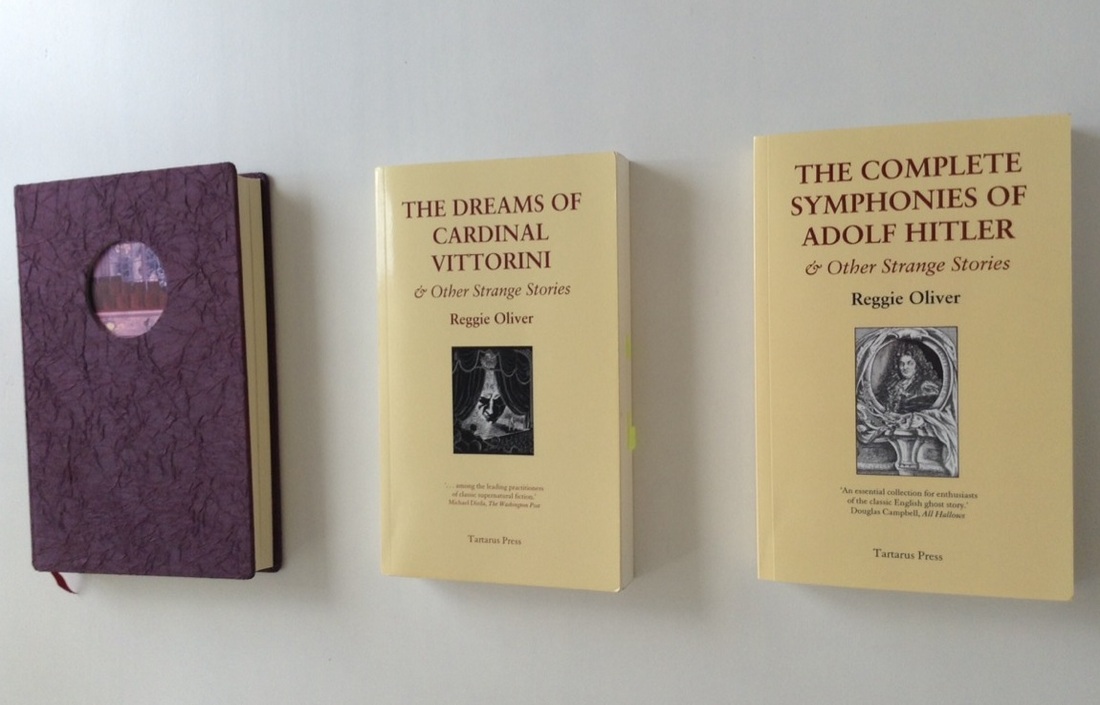

Caillois was a sui generis author that driving between sociology and literature, Latin America and the Europe, the game and the sacred: in the youth, was attracted into the orbit of the Surrealists but soon stood against the movement, sensing his own directions (as some any of his allies, Georges Bataille was the best known among them, in Acéphale magazine and the Collège de Sociologie). Escaping the Nazis, he left France in 1939 and went into exile in Argentina, where he remained until the end of World War II. In this active exile, he discovered the literary experiences developed by authors such as Jorge Luis Borges, Alejo Carpentier, Victoria Ocampo among many others that he would present to the French public in the collection of books (released by Gallimard) La Croix du Sud, already in the 1950s. Caillois sought to unify the experience that can not be reduced to everyday perception (the dream, the myth, the delirium, the supernatural, the random order) of the individual to the collective sphere, being one of the first analysts to seek a sociological, anthropological and political reading these seemingly fragmentary, inaccurate, absurd and unreadable data, so commonplace in the kind of experience that shatter the usual existence. In this sense, the notion of fantastic would be very helpful: very important in French literature, the fantastic began to be treated more differently by critics even in the 1950s, largely due to the avant-garde work (notably the Surrealists) with the term commodification, repositioned to qualify narratives with that peculiar effect of ambiguity and disruption. In this effort is inserted the short treatise of the fantastic art by Caillois, Au cœur du fantastique, published by Gallimard in 1965. The volume is a reflection and a beautiful tribute to the theme, but soon to be harshly criticized by another critic interested in the fantastic, Tzvetan Todorov in his Introduction à la littérature fantastique (1970). The bold analysis and discontinuous intuition employed by Caillois, despite its magnitude, would have no place in the geometrical view of Todorov structuralism. Putting Caillois and Lovecraft in the same compartment, Todorov simply qualifies both as "little serious critics” (so it would not be good to find serious critics defending the theories of both) that seek to define the fantastic in terms of cold-blooded reader or a vague notion of rupture/discontinuity of the "real world”. For the Bulgarian structuralist, it is vagueness, "fallacy of intentionality" and theoretical incompetence simultaneously the defect in these fragile competitors theoretical constructs. To illustrate his point of view, Todorov makes some brief quotes from the study of Caillois without mention that Au cœur du fantastique addresses figurative, not narrative issues. But this was no impediment to Todorov, although he probably should have read, impassive, the open of the first cailloisian approach. When trying to define an effect even difficult to express, passing literally before the eyes of a spectator contemplating a painting – and that Caillois knew, such an effect would have a different behavior in literary terms – the truth is that the old surrealist goes far beyond the structuralist. Already in the introduction Caillois propose the existence of a latent fantastic effect in the nature itself encoded in images and patterns, exemplified by this little critter, the mole nose-star, more suggestive to him than a Bosch hybrid. Much more than a break from everyday legality, Caillois fantastic resembles the rediscovery of these fringes defective in our fragmentary perception, the nonsense of a project to reduce the immaterial to nothing in the name of a principle of almighty reality. The Cailloisian fantastic is the mark of a strange imagery in Reality, shattering illusions of continuity and permanence. I found this wonderful book at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo (MAC-USP) library after to track it for years – a period without internet in which such findings, when it happened, was slowly enjoyed. Therefore, I have a copy, reliable and widely used. The book, to my knowledge, has never been reissued by Gallimard or any other publisher and also has no translation. mong the narrative tools universe, the dialogue stands as one of the most complex and fertile: this interaction between the characters through communication devices (immediate or not) allows the oscillation between the said and the unsaid, expressed and hidden, true and false, intentionality and involuntary. At the same time, the dialogue connects the flow of human existence in narrative terms mimicking the numerous discussions that impart (or not) our existence with meaning. The drama, no doubt, places this tool at its center, but it arises in other conceptions of plot; for example, the philosophical dialogue since Plato, who knew how to put the dialogue in the service of philosophical exposition and irony, the element that dialogue facilitates and enhances. In this sense, the playwright, biographer, short story writer and novelist Reggie Oliver captures both the theatrical tradition and the use of dialogue as a tool to improve the irony impact, and it is one of the most skilled contemporary writers using the powerful tool of dialogue in his plots. Accomplished atmosphere builder both in short stories (in collections like The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini or The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler, both by Tartarus Press) and romances (The Dracula Papers, Book I: The Scholar’s Tale by Chômu Press and Virtue in Danger by Ex Occidente and Zagava Press) endow his ghostly plots of fierce urgency and complexity – unfortunately rare in contemporary literature.

The theatrical universe arises in many of your stories, some like elements essential to the atmosphere and ambience. However, there are plots such as, for example, "The Black Cathedral" or "Evil Eye" which, although far of that theatre atmosphere had some theatrical aspects and complex scenes. It seems to me that in this sense, the dialogues appear as the key element in such a process, the dialogue as the way to the revelation small or big details. You could talk about how is the development of dialogues in your plots. I began my writing career as a playwright, although I was writing prose fiction as well, but my first professionally published works were plays. I have continued to write plays and have had some success also with translations or adaptations of French plays. What I enjoy about the use of dialogue is that it can show or suggest without stating. This sets up a relationship with the reader who can pick up on what is happening without being told. To give a simple example. I could say simply X was very angry but pretended not to be. Or I could suggest it by dialogue by having Y saying: “You’re not angry, are you?” And X saying: “No, I’m not angry! Of course not! I’m not angry at all.” That way, you not only make the scene more alive, you manage to suggest all sorts of things without spelling it out, like X’s irritability, his hypocrisy, his possible self-deception etc. etc. It is a primary principle with me that readers should be given the space to have their own views of events, to work things out for themselves. In “Evil Eye” which, as you perceptively point out has theatrical reverberations, I was concerned with ideas about spectators and participants. A spectator merely by spectating can alter the character of what happens. Perhaps one could go so far as to say that there are no such things as spectators, only active or passive participants. Also, the theatre universe appear as a backdrop for some of your stories seems so detailed to the reader that suggest a profound experience with such a universe, a deep knowledge about the daily out of scenes dramas and questions. It is a reflection of your personal and professional experiences, or a matter of search/retrieval literary backstage narratives and plots? In any case, what about the maturation process and research in plots like “The Copper Wig” or “The Skins”? My mother was an actress and I grew up around theatres. I have always loved everything about the theatre, particularly this interplay between illusion of reality. Stories are derived partly from my own experience, partly from stories I have picked up from my mother or old actors and actresses I have worked with. Performers, when not acting, are great story tellers. For example “The Copper Wig” which is set in the 1890s, derives from a number of sources. I talked with various actors who had been in the profession before this first world war and they gave me odd little details which bring the story to life, like the theatrical Sunday trains which were often met by theatrical landladies touting for custom. The detail about lying in bed in the morning and listening to the clatter of clogs on cobble stones as the mill workers went to the factory I got from my mother. On the other hand the copper wig itself I got from my own experience. I once shared a dressing room with a bald old actor who had a variety of wigs which he had neatly arranged on wig blocks, looking, from the back, like a row of neatly severed heads. The one that particularly fascinated me was a bright copper colour which gleamed under the strong dressing room lights. “The Skins” derives partly from playing the “skins” part in pantomime of King Rat in Dick Whittington, partly from the memory of a husband and wife variety act I once worked with. I am interested in the “quiet desperation” of most lives lived in the theatre: not the stars who achieve fame and success but the moderately talented people who just keep going. I am interested in how we bear our own mediocrity. One of your stories that impressed me most was "The Boy in Green Velvet", because there is in it a universe of suggestions which we have only a vague perception, a human vileness so terrible in which the supernatural element appears only as a catalyst. The same impression astonishing, indeed, I had to read another of your flawless narratives towards construction aspects, "The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini". Both plots, moreover, using unreal objects or almost unreal (paper theatre toy, memories of a lost book) in the construction of the narrative. In your opinion, this suggestive effects would rises from the objects in the scenery? As a note, when I visited the Benjamin Pollock's Toy Shop in Covent Garden, his short story "The Boy in Green Velvet" appeared, materialised before my eyes. The toy theatre – a very English phenomenon, though it has been picked up on the continent – has always fascinated me. I think it was because of the very peculiar and strange world it evoked of 19th century theatre before the advent of “realism”. In “The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini” I used various manuscripts and documents to give us a glimpse into worlds very different from ours, strange and terrible ones, which throw back a strangely distorted image of our reality. Human beings can be very responsible for the world in which they live: the worlds of Alfred Vilier and Cardinal Vittorini in “The Boy in Green Velvet” and “The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini” respectively are fearsome and not like our own, I hope, but they have the power to infect our world, and this is interesting to me. A persistent theme in my stories, very much taken from life, is the way people with powerful egos can, if one is not careful, take over another person’s life. What difference do you feel in terms of building between shorter and longer plots, like the tales of the collections by Tartarus Press and the novels like Virtue in Danger (whose subtitle is quite suggestive, The Metaphysical Romance)? Have you any preference among these formats? My tendency has been towards the form of the longer short story or the novella in which there are several “acts” but where a single theme or image can be held to without tiring out the reader. In my two novels The Dracula Papers and Virtue in Danger I have created a world, a microcosm, in which the events occur. In the case of Virtue in Danger I have created quite a narrow and circumscribed world – the headquarters in Switzerland of a religious “cult”, but to populate it I have created a large cast of characters and a wide range of action from tragic to farcical. The short story is the most powerful medium for evoking a mood, an atmosphere, a character. In the longer form of the novel that mood or atmosphere becomes dissipated or simply too oppressive for the reader. Chekhov, Maupassant and Walter de la Mare, to name three of the greatest short story writers of all time, are all masters of mood and atmosphere. You seem comfortable in working with phantasmagorical elements associated with contemporary gadgets, from TVs to video-game consoles, which is curious because many imaginative contemporary authors (as Mark Valentine or D. P. Watt, for example) seem to prefer older gadgets or objects of another nature. How did this your resourcefulness with these new phantasmagoria objects? I believe in a metaphysical realm. I prefer the word metaphysical to supernatural because I do not see it as somehow “super”, that is above nature, but rather working “meta” alongside the physical world. In my view it is a living reality, and therefore just as likely to emerge from a computer as from an ancient grimoire. Modern technology moreover is constantly trespassing on the ancient world of magic. A few hundred years ago something like a television would have been seen as a “magical” and deeply sinister object. Equally Dr Dee’s “scrying stone” might be looked on by us as a kind of primitive television. All technology, moreover, is a two edged sword. The surveillance equipment, for example, in “Evil Eye” can be used for good or, in the case of the story, utterly malign purposes and can therefore be imbued with the evil of its abusers. In your most recent novel, Virtue in Danger, there is a quasi-religious movement and a rich row of characters, both seem emerging from a film by Luis Buñuel. Some critics, as D. F. Lewis, speech in some Hitchcockian ambience and complexities in this novel as well. Could you talk about the building of this characters in particular? Is there any cinematographic influences? Interesting you should say that because I have also written Virtue in Danger as a film script. It’s promising but far too long and I am consulting with people who are more expert in film than I about it. I naturally see story cinematically - in other word in “scenes” with close-ups, wide shots, montages, “dissolves” and the like. When writing for me really works it is often like simply describing and transcribing the dialogue from a film showing in my head. Many of the characters in this book are very loosely derived from actual historical figures most of whom I never met. But I got an impression of them from their writings and anecdotes about them told by people who met them. The key for me with characters is always speech. If I can hear them talking, then I know they have come alive. With the central character of Bayard, for example, it was that weird mixture of public school heartiness and quasi-religious pietism in his speech which unlocked his character and its inherent contradictions. People often inadvertently reveal most about themselves when they are being insincere. One of the elements that makes your stories remarkably is undoubtedly your work in graphic illustrations that dialogue with the fictional universe of the text. In this sense, moreover, is not just to “enlighten” the text, but use the visual element as a meaning boost to the expressed in the plot. In this sense, how is your illustration construction work? You write the story and then leans over to synthesis it in images or vice versa? The image is always made afterwards when the story is complete. The business of making illustrations for the story collection is done when all the stories are written and a table of contents drawn up. I enjoy doing the drawings very much because I can listen to music while working on them. I cannot possibly listen to music while writing. I never make the drawings simple illustrations of an event in the story; rather they are an impressionistic rendering of one or more of the story’s images. They therefore provide a reflection on, or an insight into the story. Here is my idea of the story, I am saying. It may give you a further insight, but it is not definitive; it is no more valid than yours, the reader’s. The chief means for understanding the story should be the reader’s imagination; my drawings are simply a little additional spy hole onto it. I have come to value them increasingly as part of the experience over the years, and I am aware that they have helped to distinguish me from others working in the genre! The irony is an effect that seems to me to arise from varied and complex ways in your short stories and novels. The way it appears, for example, in “The Golden Basilica”, “Lapland Nights” or “The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler” is almost like the philosophical work towards the destruction of apparent meanings towards new possibilities – something close to the idea of irony in Kierkegaard for example, that stated about the “life worthy of man” starting by the irony. The effect of irony in his plots possess an imaginative or philosophical source? Jules Renard in his journal wrote: “Irony does not dry up the grass. It just burns off the weeds.” I agree. Irony is the conscious expression of a realisation that there exists a gap between human illusion and reality. No truly serious writer can lack a sense of irony, but that should not preclude compassion. We should be aware of the “vanity of human wishes” and the emptiness of most human achievement, but this should not prevent us from feeling sad about it. “Life is a comedy to those who think and a tragedy to those who feel,” wrote Horace Walpole. To a writer it should be both tragedy and comedy, and often simultaneously. To put it another way, both detachment and empathy are necessary. My aunt, the novelist and poet Stella Gibbons, would often discuss these ideas with me. She derived this from her reading of the writer she most admired, Marcel Proust. Is there any interest in you towards the creation of imaginative/strange/weird fiction for theatre or film, for example? How would you believe his plots will work in audio-visual or theatrical fields? There is. I began life after all as a playwright. It is an area which I hope to explore more fully in the coming years. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. Some curious mechanisms and tricks developed by the Modern Art allowed the reemergence of the polygraph character – the artist/scientist who tries to conquer various matters of Spirit and Form available on the known and unexplored connections between Culture and Nature territories. In general, this figure is usually represented by names such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Athanasius Kircher and Emanuel Swedenborg. The polygraphic view of the universe requires a singular displacement from some concrete problem (usually technological in nature) to more abstract layers of Culture, involving language and cognition: such displacement is the work of a polygraph complex flyover and flux which marks the language limits and possibilities, even when the "theorizing" side (since inception in multiple areas of knowledge necessarily leads to a continuous effort to theorizing and justification) shows absurd, outdated or invalid aspects. Essential to the Renaissance spirit, the polygraph reappears in the Twentieth Century incarnated by figures like the Italian Luigi Russolo, the Russian Velimir Khlebnikov, the Argentine Xul Solar or the Portuguese teacher, editor, graphic, philanthropist, philologist Paulo de Cantos (1872-1979). A contemporary of Portuguese modernists like Fernando Pessoa, Cantos built a work based on the imaginative dissemination of Science in books like Astrarium (1940) or O Homem Máquina (1930-36). But, in Cantos, the imagination always exceeds the momentum of systematic dissemination of Science and History in its atrocious or beneficial consequences or constructions, by the use of a creative typographic images and text recreations from edifying volumes by scientists and philosophers.

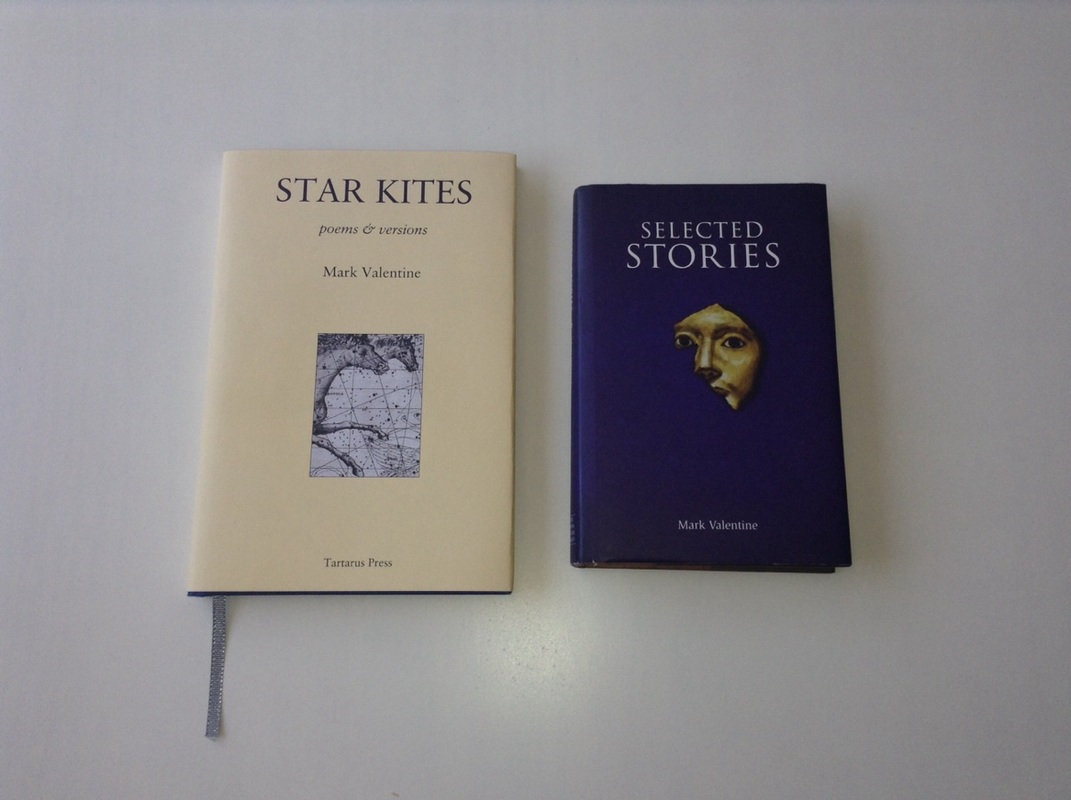

The "cantian" work – as it is known by its new researchers – invisible and ignored for long time, now beginning to be discovered by young Portuguese designers, delighted by the creative use of typographical and editorial elements in all the weird books published by Cantos. However, the original poetic language designed in complex configurations created by Cantos still await systematic analysis. Below, pictures of books Astrarium and Adagios/Maxims (1946), taken from articles on websites Montag and The Ressabiator. An interesting video produced and published by the magazine Público, addressing initiatives about rediscovery Paulo de Cantos works, can be seen here. Mark Valentine is a remarkable author who works the contemporary tradition of a kind fiction whose name is legion – fantastic, imaginative, visionary, weird, strange, uncanny, supernatural and so on. He is also had biographical works about important contemporary writers of imaginative fiction (Arthur Machen and Sarban), a scholar of the fantastic genre at the magazine Wormwood and blog Wormwoodiana. Valentine built a fictional universe full of details, filigree and subtle shifts of everyday reality in books like Secret Europe (with John Howard), At Dusk (both by Ex Occidente Press) and Seventeen Stories (Swan River Press). It is not absurd to say that this elegant fiction would be dredged by the attraction power of poetry, and it is possible to see in one of his latest books, Star Kites (Tartarus Press).

One of your latest books is a volume of poetry, Star Kites. The poems presented in the book have a tendency to disintegration of elements on the perception of reality – objects, shapes, even raw materials like marble – seemingly simple but impenetrable (as in the poem with the so suggestive title, "Marble"). This effect was obtained without tricks like objets trouvé or another surrealist intervention. Moreover, this work with the object seems inscrutable feed your creation as a writer. Could you talk a little about your relationship with this usual object, with the same matter, which suddenly turns into a fantastic element, unstable and unpredictable. In my childhood, toy marbles were usually not made of marble, but of glass: real marbles were very highly regarded. Nevertheless, though of glass, they were still shining talismans. In the poem “Marbles”, I try to evoke what these “little beautiful lost planets” meant to me as a first sign of wonder. The swirls in the marbles were mysterious: their colours were a delight. The game involved, of course, rolling these precious spheres along the gutter, to try to strike against your rival’s marble, which meant you won it from them. So there was always an edge of peril and a chance of plunder: you might at any moment lose your own favourite or gain another. And there were other risks: your marble might, as it rolled, disappear down a drain forever. So to this boy’s mind, beauty and wonder were also fraught with fragility and loss. But that did not stop the game, any more than we, mirrors of wonder, can avoid the dust. There is a noted quote by Arthur Machen to the effect that we are made for wonder, for the contemplation of wonder, and it is only taken from us by our own frantic folly. He also noted that “All the wonders lie within a stone’s throw of King’s Cross”, a busy railway station. He did not mean, of course, there was anything special about this area of London: he meant that “all the wonders” may be found anywhere. And so I have found: when we take the chance to stop and look, then a stone, a leaf, a shadow, rust, moss, rainwater, can seem to us strange and beautiful. There are also moments, rare enough, where what we see seems to tremble on the edge of becoming something else: as Pessoa said, “everything is something else besides”. I try in my writing to suggest these things, as best as I can. In the second part of Star Kites there is a work of recovery, and reconstruction, of the poetry traditions (and the poets as well, in the verge of the narrative representing some kind of authentic seer or metaphysical witness in the World) represented by a sort of opaque language (Esperanto to Portuguese, represented by two great authors of modernity in Portuguese, Fernando Pessoa and Florbela Espanca) and style (Ernst Stadler, known as German Expressionism prototype recovered in its most symbolic and mystical) to the point of view of usual reader. Not exactly a translation, but a task of essential and singular visions recovery of these authors, expressed in the poems. Thus, this part of Star Kites brought to mind the stories about poets of your At Dusk. Was there really a relationship, a joint project between the two books? As observation or curiosity, I add that "The Ka of Astarakahn" was one of the best stories I've read in 2012. Yes, both At Dusk and the versions in Star Kites come from the same inspiration, the modernist poetry of the first half of the 20th century. I think that even the most canonical figures in this field can be too little-known amongst English-speaking readers. Those who are further out, on the horizons, are even less known, and yet there is so much to discover here, so much subtle, strange, visionary work. I wrote the versions in Star Kites first, as a way of getting to know the work better: the act of translation is also an act of homage and respect. I am sure that other, better, versions than mine could be made, but quite a few of these poems had never been translated at all, so at least I have made a start. Then, after these, At Dusk is an experiment in a new form. Most of the passages mingle my own phrases, attempted epitomies of the poets, with allusive (rather than direct) quotations. This was an attempt to try something different in the way of "translation" in the broadest sense - the next step further on from the idea of "versions". As with the selections in Star Kites, I chose poets both from the acknowledged canon of modernist poetry and from further out: lesser known poets and lesser known languages. Many of those I chose were cosmopolitan in outlook, using several languages, and choosing (or being forced into) exile: their very lives and work question the validity of nationalism. The modernist poet has no nation but the library, and no language except the images of the spirit, glimpsed. Another front of your fictional creations was, apparently, the empire's twilight: there is in many of his narratives attempting to retrieve a particular universe, these crepuscular atmosphere of empires in the early twentieth century, notably the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Tales like "The Dawn at Tzern", for example, capture something of the atmosphere of this fascinating historical moment on the edge of the World War catastrophe, orderly and traditional, but carrying unthinkable chaos in its structure. Tell me a bit about your job in recreating this historic moment, if would be some consult to historians texts, for example (or, if it is the case, movies, photos, etc.) essential in recreating that subtle feeling. There has been a tendency for history to be viewed from the centre, the capital. In “The Dawn at Tzern”, I asked myself how the news of the death of the very long-lived Emperor of Austria-Hungary would be received further out, on the edges of the Empire, in some remote village. I wondered both how the news would reach the village and what effect it would have. The story tries to explore this through several characters: the diligent postmaster, the radical cobbler, an exiled priest (for what other sort would be sent here?), and soldiers in retreat from the war. The visionary youth Mishael is a shadow thrown by one of the three Jewish youths condemned by Nebuchanezzar to the fiery furnace, who came out unscathed, due to angelic protection. He is still safeguarded, but he remembers his protector in a changed way, as a form from Jewish folklore, a strange great bird. The story tries to convey the different ways open to the dying empire; duty, faith, magic, revolution, retreat. The details are mostly imagined, but it has a little of the influence of Bruno Schulz's story "Spring" and Herman Hesse's novel "Demian". Of course, I do not say it aspires to these. In the previous questions I mentioned historical issues about universes and unique traditions rebuild or evocation, in fact, this is an important facet in your work as a whole, I think. In this sense, your work as a biographer (of authors such as Arthur Machen and Sarban) and as an editor and critic (in the journal Wormwood) would be directly related, would impact their sphere of fictional production or the reverse would be correct? Yes, I was once asked why I devoted time to forgotten authors when I might be writing fiction instead. The answer is that the two fields often work well together. For example, my story “The 1909 Proserpine Prize” imagines a strange episode in the judging of an Edwardian literary prize for dark fiction, partly inspired by my reading of such work. Also, I like to write pieces where the line between story and essay is not always clear. “White Pages” seems to be about a series of authentic Edwardian novelty books issued by a certain publisher, which were mostly ways of making books of blank pages seem more interesting and exciting. Almost everything in the piece is factual, drawing on my research here, but there is a slight turn towards the end which changes the essay into a story. I may also add that when I am writing about a lost or forgotten author, and dwelling upon their life and work, it often seems that some unseen presence or semblance of the author is about, as if they are keen to see their story is told. There is a type of character that you worked a few times: the detective in themes about the occult and the supernatural (for example, Ralph Tyler and the Connoisseur, in collaboration with John Howard). However, your narratives constructed around these character types retain the visions and obsessions that could be found in many of his plots and poems. Apart from the obvious references and tributes, which would be more around these occult detectives peculiar that you invented? Are the narratives based in some historical events, facts and people? The Ralph Tyler stories, which were mostly written in the Nineteen Eighties, are usually set in my home county of Northamptonshire, an unregarded area, essentially a crossing place. They sometimes draw on authentic local history and folklore, but more often the inspiration is the landscape. It has rightly been noticed that this country reveals its mysteries more to the dweller than the visitor: for on the surface it seems pleasant but unremarkable. When I grew up there I would often walk or cycle along lonely lanes to remote villages, and I hope some of my sense of this “lost domain” might have found its way into the stories. The Connoisseur stories, by contrast, often have beneath them the idea that certain properties may be found in art or craft that will offer us a hint of the numinous or magical, and that these may be found at times in everyday objects too. The effect of sunlight or shadow can transform how we see a piece, and I sometimes wonder if there are other transformations possible too, either in how we see, or in how something is. A famous partnership in crime fiction (and film as well) was that of french authors Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, creators of plots that gave rise to such films as Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958) and Henri-Georges Clouzot Les diaboliques (1955). The partnership between of the two authors worked as follows: Boileau came with the plots and Narcejac, atmosphere and characterization. In the case of The Connoisseur, I believe that the way to creating was another, was not? How did working in partnership with John Howard? The first volume of Connoisseur stories, In Violet Veils, was written alone. In the second volume, Masques & Citadels, there were two of the stories, one about interwar Romania and the other about the first crossing of Spitsbergen (Svalbard), where I had made a good start but did not see how to go on. John was able to rescue the stories. This worked so well that we shared all subsequent stories in the series, so that John is rightly now a co-creator of the character. We also wrote a shared volume, Secret Europe, set among the cities and remoter places of interwar Europe: however, in this case, the stories were written individually and are simply published together. John has also, of course, published several volumes of his own work, most recently Written in Daylight (The Swan River Press, Dublin), which ought to be read by anyone who enjoys subtle, finely-shaded supernatural fiction. Are you working on some new narrative or project (there are many characters and plots like The Connoisseur or the poets life of At Dusk that would be fantastic in the Movies) at the moment? Talk about some of your future plans. I don’t know very much about film. I have never owned a television and rarely go to the cinema. Among current projects, a few turns of chance have recently led me back to some sound recordings I did in the early Nineteen Eighties. I was much impressed then by the do-it-yourself spirit of new wave: like many others, I published a zine and wrote for others, and issued my own tapes and contributed to others. That restless sense of just getting on and making things, even if you weren’t trained or proficient, has probably been a great influence. Recently, an experimental musician has been working on pieces based on crude reed organ tunes I recorded then: and a field recording I made (with others) of the sea and a lighthouse foghorn in West Cornwall has been broadcast regularly on an online radio station. I’m also started to look at old, time-stained book covers as a form of abstract art: how the chance markings can seem to have mysterious forms. With my wife Jo, under our Valentine & Valentine imprint, we’re also issuing handmade books of pieces that wouldn’t find larger publication: rare lost literature, translations, obscure essays and prose sketches. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. The First World War, a very complex conflict and a absurd and incredibly bloodthirsty gone through Europe, was an apocalyptic event without any doubt. It is unlikely to have been the first of its kind, but is notable for its scale: millions of dead and wounded, calcined cities, economies destroyed, crushed or "betrayed" revolutions. In this History as a sea water murky and turbulent, the vision becomes essential tool and Art wins a new possibility tied to clairvoyance, revelation, extrasensory perception, visionary activity. The Art of this kind of crisis that was Expressionism, especially in its German setting was in this sense a perfect creative expression to the distressed historical moment on the eve of the First World War. Initially a visual expression, the expressionism soon expanded to creative universes multifaceted as film and poetry and philosophy, the short time of an explosion or a lapse look capable of upsetting our perception of reality, since the expressionist proposal was to expand the subversion of the Art sphere in the galleries to political reform guided by pacifism and utopian, unrealizable systems. "Surpassed" shortly after the First World War, pushed to the space designed for the absurd idealism by perceptions that declared themselves to be "realistic" or "critical", as realize Luiz Nazario – in the essay at the volume on the subject edited by Perspective with the title O Expressionismo –, this Jewish and secular Renaissance based in the denying of the permanence and its many avatars, opting instead for the unstable direction and the constant threat of dispersion and exile. The dispersion of the death and the reality of exile, moreover, was the expressionism creators fate already during the 1914-17 War, then along the whirlwind of revolutions and strong regimes across Europe in the years 1920-30 to the seizure of power by the Nazis in Germany, World War II and the Holocaust. Thus, the artists who survived the persecutions and remained more or less faithful to the spirit of the crisis, germinal essence of Expressionism (few artists of these kind of spirit, it is true however, were converted to Nazism often to be thrown out shortly after as occurred with Gottfried Benn or Emil Nolde) could, from the distant exile view, to attend the detonations of the two atomic bombs in Japan, strange ritual closing of 1939-45 cycle that seemed to crown human barbarity, the last brick in the pile of atrocities. This happened with, among others, the extraordinary Yvan Goll .

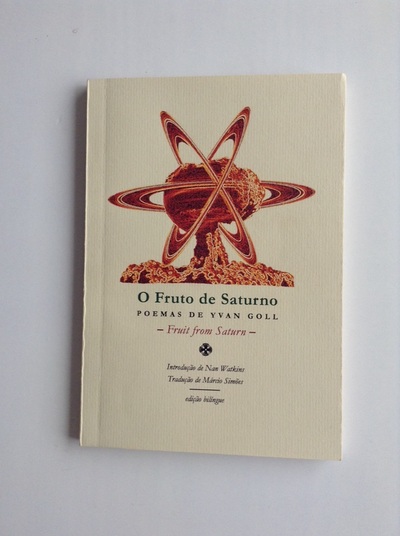

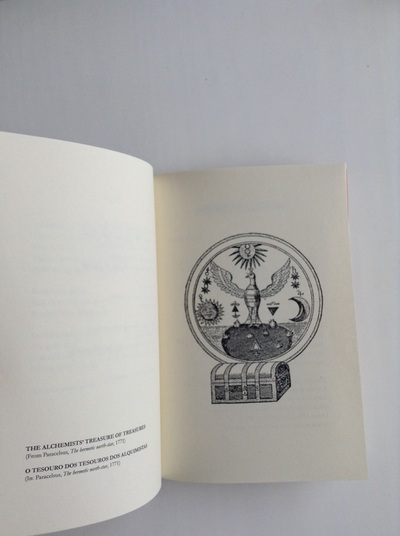

Born in St. Dié, France, in 1891, Goll represented the most cosmopolitan European culture and German face in the early twentieth century. He was a friend of Stefan Zweig, Hans Arp, James Joyce, engaged in polemics with André Breton, organiser of literary journals throughout much of Europe and USA, initially an author that illustrated the programmatic aspects of expressionism called "the social scream" by critics like João Barrento. Goll poems in this period as much like "Der Panamakanal", filled with a visionary social messianism in verses like the following (in translation of João Barrento from the collection A alma e o caos: 100 poemas expressionistas): "They knew nothing about the oceans and humankind liberation. / Nothing about the radiant revolution of the spirit." Some critics, like the Barrento in the introductory essay to the translation, may undervalue these first poetic moment images at the Goll's work, filled with an exalted and abstract politicisation, but it is undeniable that Fruit from Saturn is beyond the possible limits of utopian or merely idealized worker, science, progress, future figuration. In the face of the new, obscure and barbarous atomic myth Goll can only give the poetic deconstruction answer of this very myth through the short circuit of dying esoteric and sacred conceptions. The result is a brief and intense cycle of poems in English created during his last exile (in the U.S.), in which we could see the continuous atomic birth / destruction of the Tree of Knowledge fruits. Chain reaction, which raises the atomic energy via automatic, unstoppable process in which birth and death appear solidly connected, neutralising the long mythical dance of overcome past religions. Thus, the energy evoked by modern physics makes all the deities, extinct or persistent, laughable to put forth a Sun in full splendor in the middle of a city or in some prosaic task like driving a reactor to light a city or boost a submarine. Goll realizes very well that the new atomic religion can only be understood and demystified by the use of old knowledge schemes, the old religion and its myths: suddenly, there are this metaphysical parade where we could see Lilith, Raziel, Maimonides, Abulafia, Memnon, the Samsara. The crushed Myths resurface to salute the absolute destructiveness of the new atomic world, destructiveness that was previously only mentioned in the epic poetic imagination: "From earth arose the flaming Name / From floral whorls from spectral horns / On the high hour of death." The small cycle of poems by Yvan Goll had a deserved editorial treatment given by Brazilian Sol Negro Edições, from Natal (RN). A artisan and meticulous design work makes the bilingual book a little publishing gem with some image reproductions extremely significant accompanying each poem, plus critical introduction and an interesting manifesto authored by Goll, with his peculiar vision of surrealism. We look forward to not only new editions of the Sol Negro, but that its initiative inspires other small publish houses in all Brazil. Ray Russell runs the Tartarus Press with Rosalie Parker, but had some fiction works already published at other publishing houses (Ghosts, Russell collection of stories, for example was published by Swan River Press). In the rich Tartarus Press catalogue, it is possible to find titles by old masters like Arthur Machen, H. G. Wells and the Robert Aickman complete "strange stories" works. But contemporary writers is not overlooked at the Tartarus catalogue, with works by Reggie Oliver, Mark Valentine and Anne-Sylvie Salzman.

Could you tell something of the History of your publish house? Perhaps the first steps, initial ideas, choice of first authors, difficulties at first moments and the aims and strategies in the very first days. Tartarus Press was initially set up by me, Ray Russell, to publish a few booklets for friends and fellow enthusiasts of the work of Arthur Machen, Ernest Dowson and John Gawsworth. The first mistake I made was to use the profit from my first booklet to pay for the second, which was then given as a gift to those initial customers. For the third booklet I had to start all over again financially :-) The first Tartarus Press hardback, Chapters Five and Six of The Secret Glory, came about because I had been transcribing the manuscript of the previously unpublished parts of Arthur Machen’s novel, and various friends asked if they could have a copy when I had finished. Publishing it as a proper hardback book was the most sensible way of making it available. The main problem I encountered in the early days was unscrupulous printers who told me they could print a book for me, but obviously couldn’t! Finally I found The New Venture Press, who had not printed a book either, but were honest about it. We worked out how it should be done together, which was very instructive. Then we had to find binders… In those early days it was a hobby, without any idea that I might try and make a living out of publishing, as I do now. Some publishers have a unifying vision or even a principle, a theoretical formulation that serves as some kind of guideline. There would be something similar in the case of Tartarus Press? It would be possible to define your editorial house with an idea, a word, a speculative notion? I started Tartarus with the idea of simply publishing and sharing obscure writing that I really enjoyed. My partner, Rosalie Parker, joined Tartarus about fifteen years ago with a determination to do exactly the same thing. The publishing policy of Tartarus is still guided by our personal literary tastes. In my vision, I realize that there are two paths preferred by Tartarus Press: one, digging in the early, forgotten and/or traditional imaginative works by authors like Arthur Machen, Thomas Owen, H. G. Wells, Robert Aickman, etc. The other one, more focused in contemporary authors like Reggie Oliver, Mark Valentine, Nike Sulway among many others. There are, in this dual pathway, some kind of balance between two sides, even in the editorial choices (authors and titles)? We see the historic and the contemporary writers as being complimentary. A love of the work of Arthur Machen led naturally to us publishing Walter de la Mare and Oliver Onions. L.P. Hartley took the supernatural fiction genre further forward into the twentieth century, and Robert Aickman was their natural modern successor in the second half of the century. And by publishing contemporary, twenty-first century authors like Simon Strantzas and Mark Samuels, there has been a line that can be traced back down through all those writers I have already mentioned. Obviously, Angela Slatter and Nike Sulway are writing in a slightly different tradition, and Reggie Oliver with a different background again. The Tartarus Press editions, even in the paperback form, are beautiful in every sense. The short-run editions is a huge indicate of this precious work. But there are a solid investment, as well, in e-book edition, with the careful attention to nearly all formats available. This editorial vision at Tartarus could be a way between physical and digital war format in the book market, perhaps? Are there plans to expand the digital production at Tartarus Press? At heart we are book lovers, and nothing can replace the enjoyment of reading great fiction in a well-made book. As soon as I started to understand book production, I wanted to produce beautiful editions that I would want to keep and read myself. It was tempting to try and print books letter-press, and have more bound by hand, but we didn’t want to make them unaffordable. I hope we have a good compromise. But realising that our limited edition hardbacks are still perceived as expensive by some readers, paperbacks have been introduced for reprints. We still try and make them as elegant and nicely-produced as possible. Ebooks are less enjoyable to produce. We know, though, that for some people they are very convenient. It has very hard to sacrifice so much design work to create ebooks, but we make them as well as we can. Are there a best/favorite edition or collections for the Tartarus editors? As with your own children, it would be unfair to choose some over others! A recent edition, The Life of Arthur Machen by John Gawsworth, had a interesting extra: a DVD with a BBC film about the book theme. This is a familiar format for the Film Art collectors (usual at some DVD/bluray labels like the American Criterion Collection) and it's great to find in a book with the already mentioned Book as Art Object vocation. But are there another plans for editions with films and audiovisual material as bonus/part of the edition? There are no immediate plans for us to become multi-media publishers. The John Gawsworth DVD was a fortuitous opportunity that we couldn’t afford to miss. We will always be primarily an old-fashioned print publisher. In the same way of the last question: what about the Tartarus Press future plans? More translations or the archeological task of Master Works restoration? We are superstitious about discussing future plans, because announcing projects too early often means there is some reason why they are then delayed… We do have new books by some great contemporary authors on the horizon – some known and some unknown… This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research. The short story "La escritura del dios" by Jorge Luis Borges (published in the collection El Aleph, 1949) presents an intriguing plot: a priest (perhaps an Aztec priest) is trapped in a dark and gloomy dungeon by the new SPanish rulers, with only a moment of light by day when receiving meal and water. The only other being in prison is a jaguar (later called the Tiger), which shares with the priest the same narrow, dark and miserable space. The priest, plunged into despair and boredom, finds a task: to decode a secret message that his god wrote somewhere, in the large space of the Nature. With a insight, the priest discovers that the pattern of spots on the skin of the big cat in the cell is not random, but the encrypted message from god (as the title tells us, though the protagonist once mention "gods") and he, the chosen one to decipher it. A message of power, revenge and destruction, weapon of mass destruction that the priest, however, does not trigger simply because, after the discovery of the absolute, the human contingencies seem distant, incomprehensible, frivolous for him. The message of god, we know by the plot, is a total word, which encompasses the universe, what came before and what is after. But now imagine that god decided to write an encyclopedia, a volume that includes knowledge of various disciplines into a synthetic whole. It is likely that this encyclopedia follow some rules of the genre: perhaps a didactic division between the knowledge in areas like technological devices, geography, fauna, flora, history. Although this encyclopedia includes elements of our world – after all, also part of this god's creation – these elements do not appear in the spectrum of our usual understanding. Would be transfixed, perhaps even by the mood of such a god, a mood that could be, in any case, dark or sinister. Although we have made a brief and idle speculative exercise from a plot of Jorge Luis Borges, the truth is: this encyclopedia has already been created and its name is Codex Seraphinianus.

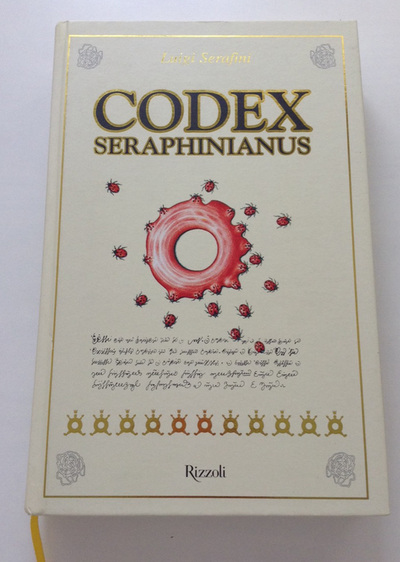

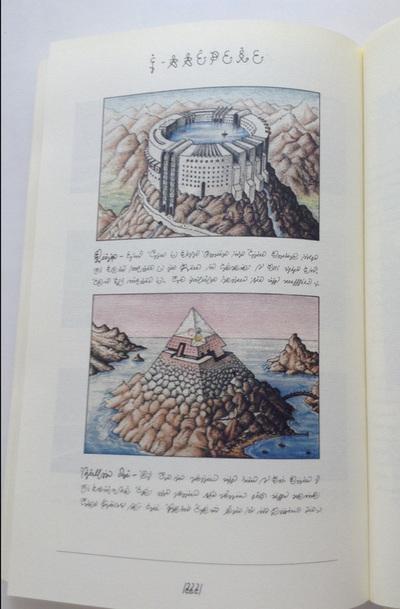

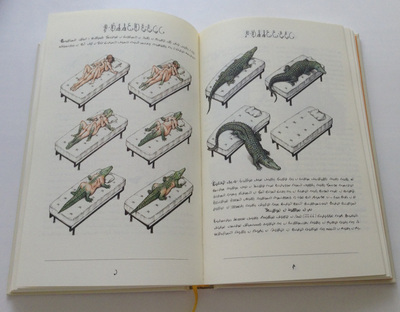

Originally a manuscript built by the Italian architect Luigi Serafini between 1976 and 1978 – the complex and whimsical pictographs, alien characters entirely invented, and the illustrations –, was published in 1981 by the luxurious and prestigious Franco Maria Ricci in two volumes, with a Italo Calvino introduction, "Orbis Pictus". The author's declared source was the enigmatic Voynich manuscript, fifteenth century codex in strange alphabet, never deciphered. The essayist Alberto Manguel, who was FMR editor in the early 1980s, was the one who received the bulky serafinian manuscript by mail. In his book A History of Reading, Manguel recounts his encounter with this strange manuscript, calling the work "one of the most curious examples of an illustrated book I know", created "entirely of invented words and pictures", something that forces the reader to a process of decoding the text without the aid of any formalized natural language. It is an invitation to the reader to transform the usual reading activity into a dynamic process of interpretation/creation of a young, wild and throbbing universe. Thus, the elements of the book are not entirely alien: it is possible to recognize human figures (the whole or cut into pieces, sectioned to perform new functions: eyes that turn into fish, for example), animals, plants, technologies (for cars with melted parts or made of unusual materials) etc. You can also see, in the same manner, that the strange alphabet is provided with a organization process with elements in common to human languages: clauses, sentences, titles and so on. However, this perception does not contribute to the advancement of understanding, capturing or establishment of the text definitive meaning. Instead, gave rise to ambiguity. So, if we can find some recurrent features in the serafinian images and text – for example, the principles of fusion and transformation – we soon discovered that there are other principles permanently conflicting with, and the irony that runs through these pages just neutralizes categorical definition. Franco Maria Ricci has released two editions of the book (in two volumes and as a single volume), both sold out and reaching astronomical prices on specialized sites and bookstores worldwide. Later editions of other publishing houses are rare, all sold out, as the versions by Prestel (Germany) or Abbeville Press (USA). The latest edition (first issue came out in 2006 and the second in 2008) is the Milanese Rizzoli, much cheaper than usual for the luxurious album. Serafini, meanwhile, continued producing beautifully illustrated albums, like Pulcinellopedia (under the pseudonym P. Cetrullo) or an illustrated version of Les Histoires Naturelles by Jules Renard. This books are even more inaccessible and invisible, rare pleasures for rich bibliophiles. Anyway, it is curious that Codex Seraphinianus has gained cult status on the Internet with amazed articles on websites and publications like The Believer or Dangerous Minds, given the limited and short publishing history and the type of challenging "reading" activity proposed by this book. Maybe it's the fact that the reading of this strange encyclopedia whose content is a knowledge supposedly universal anticipate what we see at Internet, a entropy whose chaotic surface is unfortunately far from possessing the same wry humor. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed