|

The embodiment of terror in the mind and the perception structures, unstable, a perpetual spin, beginning and ending in cycles that could be endless. The devil, not as a folkloric, horned figure, but as a feasible existential possibility, a everyday chance, although not at all trivial. The horror story as an experiment, an outburst, musical harmony, as a new roman by Jean Ricardou or Alain Robbe-Grillet. That's all about the collections of short stories The Light is Alone and Malingerer, wide fields of audiovisual findings, diabolical presences, complex and unspeakable constructions. The author, Thomas Phillips – writer, composer, theorist – whose interview follows below.

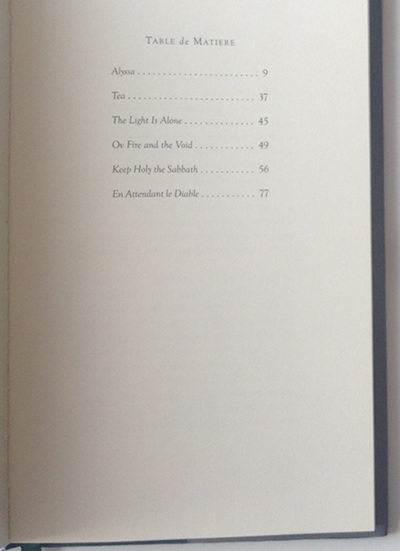

A interesting element in your narratives is the ritual, the stylized way of life used by the characters in their interactions. Of course, some plots directly address the ritual – "Alyssa", "Keep the Holy of Sabbath", "The Evil Thereof", "Hideous Gnosis" – but in all his tales of the books The Light is Alone and Malingerer, the reality is constantly ritualized by characters, so can (or imagine) get a complex interaction with the universe around them, that is, the ritual is like a process of our nature, as meaning that we commonly use down in a universe of random repetitions and little sense. This conception of ritual emerged from some reading/theoretical interpretation or developed as a narrative construction aftermath? This is a fascinating observation, particularly in so far as I tend not think of ritual as constituting defining moments in the stories. Rather, it is more aligned with formulas that emerge from the milieu of the story itself. Satanists engage in ritual, as do fundamentalist Christians and black metal musicians; it appears in my work, then, as a kind of prop, as opposed to a theoretically-informed anchor. This is not to diminish the general significance of ritual in everyday (or exceptional) life, though I'm mostly interested in literary style and form over such content. I realize in reading your stories, a complex approach to spatial displacement: places that lose their usual concreteness (the dentist's office in "Ground Drilling" or the beach in "Ov Fire and the Void") or characters that become, in a way or another, exiles, expatriates, individuals who are forced to displacement by external, unmanageable forces. This spatial issue arose by personal experiences? How did you get this approach to the exile, the instability of the usual space? I've spent significant periods of my life living abroad, in Finland and Quebec, in addition to casual traveling. Though these experiences have been largely positive and formative of what is perhaps an idiosyncratic literary sensibility, at least in the context of American fiction, they have certainly provided a taste of displacement or dislocation that is inevitably as challenging as it is productive. One can go a certain distance in determining the quality of one’s interiority, in controlling one's reactivity, but the external forces you mention may be especially robust when acting on us in relatively unfamiliar contexts, which of course is an excellent reason to live abroad, to abandon, however temporarily, what is safe and comfortable. From a theoretical perspective, I've always been keen on Viktor Shklovsky's notion of literary defamiliarization, of removing an idea, a character, or an object from a familiar context and placing it elsewhere so as to produce a novel perspective. I suppose this is what we do with ourselves when leaving habitual terrain, be it geographical or psychological. Some of your stories deal with the baffle interpretations by humanities and social sciences at our time, by the use of exquisite and sophisticated irony. Philosophy, semiotics, anthropology and some analytical social conceptions arise especially in Malingerer (I think the first tale and "Hideous Gnosis” as good examples). His interest in these disciplines is related to research or emerged as a form of ironic treatment of excessive systematization of our perceptual reality, a veritable trap of all our systems of meaning? I was introduced to post-structuralist and postmodernist theory as a young literary student and was immediately captivated by its resonance with certain religious or mystical ideas that had come to inform my sense of humanity's severe limitations as well as its prospects of more or less transcending the latter. Theory can doubtless be excessive in so far as it operates as yet another mere institution, a doctrine that ultimately elevates the ego, particularly one in process of chasing an academic career, though it also has much to teach us regarding said limitations and, in a few cases (Deleuze comes to mind), techniques of unblocking ourselves, of stripping away the paint of normative ideology and hegemony. With horror fiction, I tend to be most concerned with exposing impediments and blockages, particularly those that arise from rather gruesome power structures. Of course, I’m also interested in the presentation of unsettling atmospheres, creepy, confrontational ambiance. In my opinion, the element that makes the HP Lovecraft's fiction extraordinary is the systematic use of synesthesia for narrative construction – the monsters, the scenes, a whole world emerges from evocations based at the crossroads of senses associations. I think your stories have, accordingly, certain resemblance to the Lovecraft work: in them, there is also the systematic use of synesthesia. Although the central element of perception in your plots seem to be aural because the characters construct and deconstruct scenes and moments using auditory perception, by the sounds that evoke images, colors and movements. What strategies do you use to build this universe of indirect perception? How you work out the synesthesia and the aural assault, in preparing your fictions? I must confess that I don't evoke a particular strategy in this regard. That said, music/sound/listening have always been important in my life, so it's no surprise that they emerge periodically in the writing. Another way of addressing this issue is, as the question suggests, to reference other writers. Lovecraft is certainly an influence. I think, too, of Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House and the manner in which the house manifests its anthropomorphism via sound, how it affects the senses with relative nuance. Perhaps we could even speak of a synesthesia of influence, of how particular words and tones, their signification, provoke related but divergent responses in a reader/writer. Your production is multifaceted, wide: there are essays, novels, short stories, musical compositions. Theory, narrative, music. On the other hand, their narratives reveal a close co-existence of all these elements, especially by synesthesia and ritualization (in the case of the theoretics). How the narratives came under your creative possibilities? Emerged as a result, simultaneously or preceded other activities? As it happens, my initial forays into creative writing, as a young teenager, explored the horror genre. Jackson, Lovecraft and Clive Barker were my primary guides. It was only later, in my twenties, and following committed, university literary studies, that I began writing novels prompted by the "synesthesia" of reading different writers – Kundera, Duras, Hesse, Baldwin – a peculiar assortment. By the time I discovered contemporary French writers associated with publishing houses such as Éditions de Minuit and P.O.L., I recognized a literary voice, or voices, that I had to make my own. Writing has been a staple throughout my life. The same can be said for music as well; as a listener and practitioner, I've never been without it. Inevitably, the disciplines (and they certainly require discipline) inform one another, which speaks again to your observation about the role of sound in my stories. While my novels tend to focus on the psychology of the quotidian, with few of the trappings of more conventional fiction, horror is a unique pleasure for me because it relies on provocation of the senses. Though my horror fiction isn't especially conventional, relying, like the novels, as it does on a minimalist aesthetic, the genre requires tension born of atmosphere, (in my case) a modicum of but a charged and immediate mode of description. If the novels are akin to a minimal, delicate music composition, the horror stories, though still reduced, are more aligned with a short blast of harder, heavier music. Theory, of course, is yet another writing mode that offers its own pleasures, and like other genres, is one that is always evolving in my practice. How to maintain a level of stylistic ingenuity, to balance this with clarity, and still operate within the confines of certain academic formulas – this is an ongoing effort for me. The infernal power is a recurring element of the tales of The Light is Alone and Malingerer, although the evocation – so to speak – of the demonic being is never straightforward. Your devil is a possibility, a suggestion, a peculiar form of Nature not bend to human plans – even in the case of some soi disant adepts. The demoniacal force comes suddenly, an inadvertent event even for those who are waiting eagerly (as in the short story "En Attendant le Diable"), a possibility impossible to frame in traditional tables of philosophy, history, theology. How did you come to this original narrative perception of evil? What, in this sense, your main influences? There are two central points of origin here. First, I enjoy horror that examines not simply the figure of Satan, which of course I regard as nothing more than a myth, but human – all too human – practitioners of Satanism, people who are inevitably flawed, damaged, or simply over-invested in the ego and yet, as a result of their suffering, manifest exceptional power in the context of quite ordinary, bourgeois society. Such characters make for fascinating narrative constructs in so far as they speak to a general dis-empowerment in the everyday and our collective yearning for agency. And naturally, as with any fictional form, the uneasiness that almost invariably results from efforts to advance tipping over into raw egotism is tremendously seductive. Like most readers, I receive a kind of perverse pleasure from the violence of witnessing people rise and fall. Which is not to say that I'm in any way misanthropic or particularly negative. Consider the incredible tension in the children's stories of Dr. Seuss or Charles Schulz. On the other hand, there are real dangers in the world, all of which, I believe, can be understood from the perspective of unconscious, reactionary modes of being. Terry Eagleton makes the point that reactionaries, in the form of religious and political fundamentalists, those of us who haven't the self-respect or motivation to think critically and intellectually about what it means to be a self among others, are weighted down by a surfeit of being, a crystallized or monolithic identity, as opposed to the non-being that allows, and indeed, compels one to embrace a more fluid and open existence, which, of course, is the nature of our collective experience, try as we may to impose embarrassingly absurd and paranoid boundaries around ourselves. This condition signifies true evil to me – unconsciousness – the face of Satan that is far more frightening than any horned figure. Hence a Tea Party Rally as Black Mass in the story "Tea,” or an evangelical school teacher whose patriarchal neurosis around sexuality, Biblical literalism, and a particularly American work ethic finally summons a rather vicious demon. The structure in the tales of The Light is Alone and Malingerer seems to favor the narrative as a short form – even though there is the suggestion that the tales of the two books have resonances, closeness, including by this curious sequel relationship between "Alyssa" and “Malingerer (is That you, Alyssa?)". The decentralized, fragmented construction with incessant new beginnings that we see in your tales benefited the choice for short narratives, these diabolic tales? Have you any plans to expand these tales in a much longer narrative someday? Despite the gravity of my response to the above question, horror is first and foremost a source of joy for me as a writer. I love reading it, watching it. As such, the short story format is perfectly suited to my ambitions in terms of occupying relatively short bursts of writing that may be, ironically, even more experimental than my novels to the extent that I give myself the freedom to do anything with the former – as long as it communicates a sense of darkness. So at the moment, I don't have any concrete plans to write a horror novel, though it isn't outside the realm of possibility. I've just finished the first draft of an academic book on liminal narrative that addresses horror in a longer form and, I must say, this experience was delightful. So perhaps I will turn that theoretical lens toward an extended burst of fiction at some point. The question makes me think of T.E.D. Klein's wonderful story, "The Events at Poroth Farm" and how I remain anxious about tackling the related novel, The Ceremonies. I suspect this is my loss. Interview conducted with support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed