|

In the film Andrei Rublev (1966) directed by Andrei Tarkovsky there is a curious scene, bizarre though valid and feasible from the point of view of a cinematographic work that was intended to be a historical reconstitution of the invisible, that is, the life of Andrei Rublev, the enigmatic Russian artist who lived in the fourteenth century, acclaimed as the most important and recognized icon painter in the History of Russia. When one character in the film, Kirill – another icon painter, extremely erudite and bookish – back to his monastery after years of wandering (recounted in episode 6, “Charity”), he realizes that a group of horsemen are being projected projected upside down on the wall opposite to the window which is closed by heavy shutters. Despite the barriers in the darkened room's window, there is space for the entrance of a tiny light beam, responsible for the marvelous and brief projection. A mediocre painter of icons, Kirill intuitively discovered the secret that afflicted the art from ancient Greece in this ad hoc camera obscura: the discovery of a method for capturing the movement of life, shaped in moving pictures. But that's not enough for Kirill to escape his own mediocrity – although inventive, he would never emulate/rival Andrei Rublev, a painter who did not need technical apparatus, narrow references in the tradition or prefabricated epiphanies. What Rublev did was paint a vision – the reality of the universe and the imagination – which only he had, something inaccessible to reproduction, even if a very sophisticated technique were employed. But humanity would pursue in devices and technological utopias the views articulated by Andrei Rublev (or Michelangelo, or William Blake, or Francisco de Goya, or Vincent Van Gogh, or Francis Bacon): cinema is perhaps the most stupendous result of this millennial effort that is both an attempt to capture the movement of life as a way to reproduce visions which we have access to only in the contemplation of great paintings or unique epiphanies.

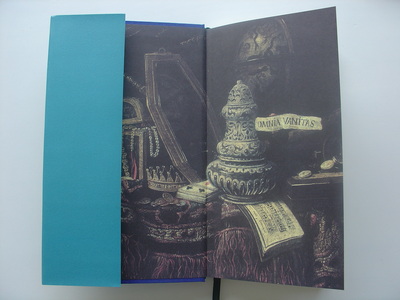

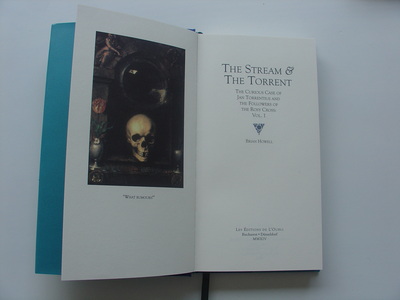

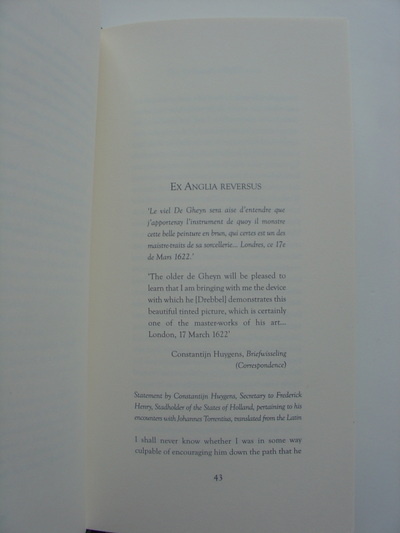

It is curious that this intuitive discovery in Tarkovsky's film, although entirely fictional, is still achievable. The history and origins of the camera obscura are large, mythical and erratic, appearing in ancient China and in the Aristotle's researches, in the medieval Arab Engineering treatises and in the experiments by Anthemius of Tralles, the mathematician who designed Hagia Sophia in the days when Istanbul was still called Constantinople. The Ancestral Skyline of History has some fixed points with conventional nomenclatures, so in the context of what we usually call “Antiquity" and the "Middle Ages” – general names for didactic purposes – the knowledge protruded from much more complicated paths that nowadays, with unifying processes, databases, instant media, systematical records or patents. The obscure details and possibilities of the past added to the desire to achieve what might be called absolute image – a paradox which brought together the perfect reproduction and the imaginative vision of complete beauty – is what fuels the extraordinary novel by Brian Howell, The Stream & The Torrent (subtitled The Curious Case of Jan Torrentius and the Followers of Rosy Cross: Vol. 1), released by Zagava/Ex Occidente Press collection Les Éditions de L'Oubli in 2014. It should be noted that Brian Howell is not a newcomer: he delved into the intricate and fascinating cultural universe of the seventeenth century (with a focus on Vermeer) in his first novel, The Dance of Geometry (2002). He also wrote a short stories collection on contemporary Japan, The Sound of White Ants (2004), recovering both Japan's tradition in his foreigner’s point of view in the style of Lafcadio Hearn and the works of Yukio Mishima. In The Stream & The Torrent, Howell returns to the world of artists, scientists, inventors, noblemen, conspirators and charlatans of the seventeenth century, but the focus is no longer a well-known painter. Johannes Torrentius (1589-1644) – who has adopted a Latinized and slightly modified version of his Christian name, Johannes van der Beeck Symonsz, in which “Beeck” means “brook” – was considered a master in Still Life already in his time, but this recognition did not prevent much of his works being burned due to accusations that the painter was a member of the Rosicrucian Order, an adherent of atheists and Satanist beliefs. The reputation of Torrentius preceded him: he was seen as “seducer of burghers, a deceiver of the people, a plague on the youth, a violator of women, a squanderer of his own and other’ money”. He stated that his works paints were “other", his paintings were the result of some kind of magic, that "it is not me who paints”. Eccentric and arrogant, he was arrested, tortured and condemned to the stake. He was saved by the king of England, Charles I, and became his protégé in 1630. For some time, Torrentius lived alone in England, at the expense of its powerful new boss. But in 1642, he had to leave his comfortable exile in London, perhaps due to the perception that the recently started English Civil War would lead his patron, fatally, to be beheaded. Torrentius returned to the Netherlands and was arrested again for some time; finally released, he went to his mother's home to die, some say due to a relentless syphilis infection. A February 7, 1644, he was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), a remarkable fact when considering the rumors about the deceased and his atheism, heresy, blasphemy and devil worship. His works have disappeared without a trace: part of them in the first imprisonment. Some works could have survived through the English exile; in fact, the inventory of Charles I mentions several paintings by Torrentius but none were found later. Only one of his works survived to be discovered in the twentieth century: Emblematic Still Life with Flagon, Glass, Jug and Bridle (1614), an extraordinary and complex allegory of moderation. The reflections' shadow-play in every surface of this painting – metal, glass, wood – seems to build a fiery and dark universe of fantasy through strange shadows and mysterious ways. This amazing painting, the only work by Torrentius that has come down to our time, it is one of the central devices in Howell's novel. The Stream & The Torrent is divided into three chapters: “Vandike and I”, “Ex Anglia Reversus” (poetically evocative and powerful expression, which was for some time the working title of the book) and “Cornelis Drubelsius Alcmariensis”. Each chapter presents a fragment of the mysterious life and work of Johannes Torrentius from a privileged witness’s point of view. In the first chapter, the very Johannes Torrentius, in a kind of diary, describes his exile in England and attempts to retrace his artificial and complicated processes to capture the life in images with blood, magic and a sort of art. In "Ex Anglia Reversus", the witness is Constantijn Huygens (father of the scientist Christiaan Huygens, inventor of a device which was the precursor to the cinema called the magic lantern, according to the historian Laurent Mannoni's researches in his book The Great Art Of Light And Shadow), the arbitrator in a strange duel of still lifes between Torrentius and the father and son De Gheyn. Finally, in the last chapter, the testimony of Cornelis Drebbel of Alkmaar, renowned for inventing the oven thermostat and for the construction of the first functional submarine; Drebbel reports his experiments alongside Jan Torrentius in London and Prague to the powerful final narrative hook. Historical characters intersecting each other in contexts not only credible but feasible: there are political games, palace intrigues, aesthetic discussions and bizarre/useless or cruel (depending on the point of view) inventions. This is a complex narrative texture, centered in fragmentary testimonies: the uncertainty of first-person narrative is multiplied by authors' distortions and manipulations, as well as the perception and reading of every fragment. The elaborate poetic construction made by dubious patches and a testimony that apparently can only be taken as true after a process of systematic collation – exactly what remains of Johannes Torrentius fascinating personality. Above all, the novel The Stream & The Torrent is a brilliant allegory of cinema, the human dream (achieved thanks to the technology) to capture life in all its detail, as through a dark process of black magic. In this sense, Brian Howell approaches Adolfo Bioy Casares novel The Invention of Morel, but exceeds the Argentine author to work not with pure fantasy invention of a machine that captures the substances and then plays this substance endlessly through a perpetuum mobile mechanism. Wonderful idea/image, but also conventional. Johannes Torrentius's “other paints” and camera obscura have an unstable concreteness provided by historical accounts, vague memories and dubious records; it is both a feasible (but unrecoverable) invention, a fraud, a hoax, a sleight of hand, a prodigy. The book, physically, follows the standard defined by the editors Dan Ghetu and Jonas Ploeger: it is an indisputably beautiful work of art. The printing is magnificent, on heavy paper with balanced typography, which reminds us of an updated version of the books that Torrentius and his friends manipulated in the seventeenth century. The internal images – curiously, none of them made by Torrentius – are beautiful still lifes of the seventeenth century, which guarantee to preserve a fully adequate air of mystery. We can only wish that the second volume is released soon, so let us enjoy the delicious, turbulent and atrocious Johannes Torrentius and his adventures in his quest for the absolute image while traversing the intricate conspiracies of this imaginary Rosicrucian Order. NOTE: Some of the historical references in the article above – especially about Johannes Torrentius – came from a series of articles (in three parts) quite enlightening by Maaike Dirkx entitled “The remarkable case of Johannes Torrentius” available at https://arthistoriesroom.wordpress.com/?s=Torrentius&submit=Search. The excellent review by Des Lewis, available on his website (https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/2014/10/24/the-stream-the-torrent/) is very useful and intriguing as well.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed