|

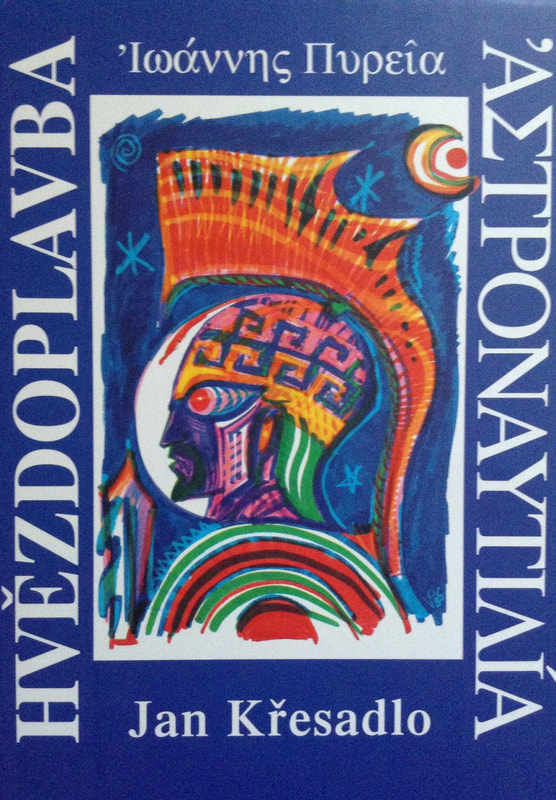

Some books have a special impact from their very existence, their being in the world; by not having a standardized presentation, a conventional exterior structure, become objects of fascination even before they are opened. Some present a strange, shocking or extraordinary cover illustration, this image being its source of magnetism more evident and concrete. Thus, the French translation by François Rivière of the J. G. Ballard’s novel The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), entitled La Foire aux Atrocités, published in 1976 by Editions Champ Libre – for the collection Chute Libre (“free fall”) – presents one of these extraordinarily picture with some striking layers. It is a kind of portrait, in the form of an illustration whose authorship is unknown, in which we have a face (female, probably) obliterated by blindfold and gag. The colors of the image (deep red, green, light brown, black that creates violent contrasts) are powerfully evocative, though the image itself has little to do with the content of the book, rounding the sex, yes, but not that way. Another more complex way for a book to express its potency in itself is by its volume, the way its outward structure is presented to the reader – in this sense, the recent collections Booklore and The Whore is This Temple are magnificent in a peculiar way. The first one, evoking the multiplicity of a library by its conflict between format and content; the second, because it is a kind of impossible object, a contemporary grimoire for personal rituals although it is not that, in fact, but a collection of narratives and poetic creations. Astronautilia is close to these two trends, but in a very unique way, because their impact happens in successive waves, that plays with expectations of the reader from one seemingly surpassed fright to another, culminating in a very own final decisive impact. In its dust cover, with a strong blue tone, a suggestive illustration by Václav Pazourek, the first image of the book and its real gateway: a portrait, in profile, quite colorful (the style suggests a vaguely primitivist expressionism) of what appears to be a warrior of the past, probably a hoplite of Ancient Greece. It is possible to identify in the image the shield, the helmet, the spear that this soldier holds. But the illustration, however, escapes this determination of meaning by a trait of technological futurism that runs through it – the white space between the face and the background of the image suggest an astronaut's helmet, adapted for use in sidereal space; the elaborate arabesques in the helmet suggest a civilization and a history that are not entirely human; the eye of the hoplite, at last, with a stylizedly almondlike shape and multiplied (by lenses? Or it’s an alien eye, in fact?) by the subtle effects used by the illustrator, a secure support for the odd strangeness. This extraordinary image covers and contrasts with the hard cover, much more austere – gently marbled dark blue, with the Greek part of the title engraved in silvery tones while the Czech part is in low relief – which refers to collections such as translations of classical and bilingual (Greek and Latin, of course) works published by publishers such as Éditions Les Belles Lettres. But the impact of the dust cover rich imagery, the fastness of the cover, and even the volume of this reasonably thick book constitute the first moment, preparing for the still greater impact with what we might call the linguistic discovery of its contents. For in the very first pages the reader is threw in a confusio linguarum of considerable proportions: there are texts in English, Latin, Czech – but all this is only the preparation to the poem, thousands of hexameters in glorious Homeric Greek handwritten.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed