|

Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, in a particularly fierce aphorism of their Dialectic of Enlightment latter section – a treatise about the rationality booby traps – saw some similarities between the haruspex in a pagan altar and the professor working on a dissecting table of a ultra-modern laboratory. For the two German philosophers both the priest and the scientist represents the Man and the Humanity devoted to the ecstatic observation of Nature in bloody agony, slowly tasting the perverse pleasure that such activity can provide. Of course, it is not the suffering of Nature as a totality, since the focus is on the potential and preferred victims, seen as the weakest links in the terrible chains of natural and social logic – captured animals, the natural sources with easy access, peaceful and isolated communities, segregated human groups, women – chosen for sacrifice. When faced all the blood, viscera, and the torment of open wounds, the owners of knowledge (scientific or ritualistic) seek signs, evidence, portents. So this brief aphorism, titled “Man and beast”, presents the thesis, central to Adorno and Horkheimer philosophy, that the brutal and fearful exploitation of Nature reflects the brutalization of man from the remotest origin, the most distant historical sign and myth. The devastated Nature and the Humanity enslaved reflected each other, lighting points, details and degrading aspects. Thus, the fierce and brutal Cannibals of West Papua, a novel by Brendan Connell recently launched by Zagava Press not only takes up the thesis of the philosophers like Adorno and Horkheimer as the turns inside out their propositions, thanks to the almost unlimited resources of an intricate and fluid narrative, which gives the reader the vertiginous sense of risk, as we should possibly feel when entering an unknown and uncivilized jungle.

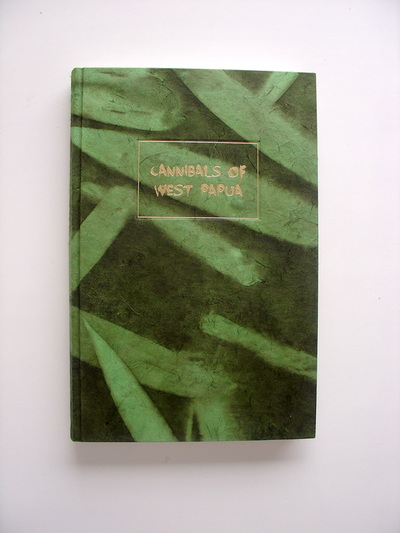

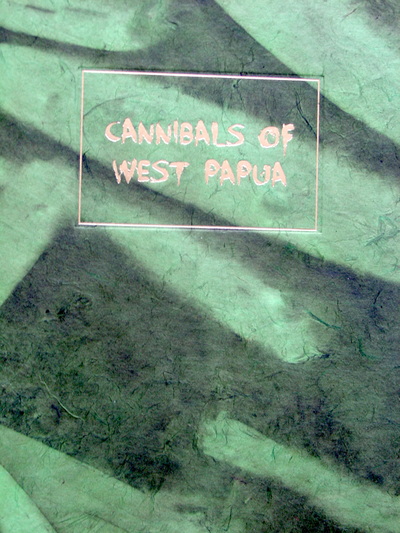

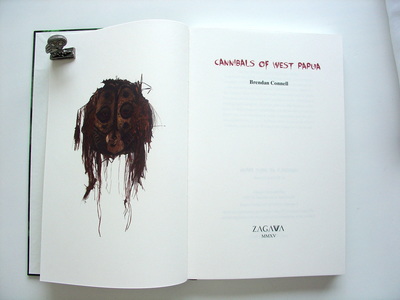

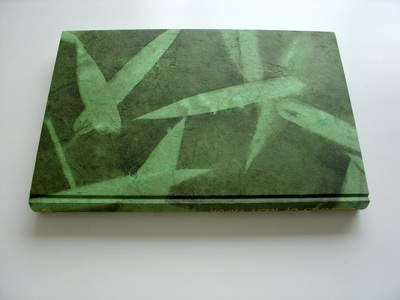

On your journey to South America in 1832, Charles Darwin was deeply impressed with a native tribe of Tierra del Fuego living in a primitive state bordering the unthinkable to the young Victorian naturalist: “One can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow-creatures, and inhabitants of the same world”. This tribe, the Selk'nam, had a kind of photographic testament in a brief peaceful moment before the extinction thanks to the Martin Gusinde, an Austrian priest, between 1918 and 1924 (these photographs were published in the book The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego). The Gusinde arduous struggle to preserve at least the image and the memory of the Selk'nam conflicted with the genocidal fury of Julius Popper, a Romanian engineer who performed manhunts since the early 1890s with the intention of pacifying the territory, facilitating the work of miners and ranchers. It would not surprise if the Patagonian Indian hunters – adepts, by the way, of the documentary photography, especially to record the dead human prey – imagined that the Selk'nams, with their stylized and complex rituals, were cannibals, a powerful argument to help in the rationalization of murders. A hypothetical meeting between Gusinde and Popper (impossible, for the second died peaceful in 1893), in turn, would be an interesting opportunity to put face to face antagonistic perceptions of savagery, civilization, progress, dialogue, peace. The Cannibals of West Papua central characters, Don Ramiro Duarte and Fr. Massimo Tetrazzini embody the extreme positions of civilizational scope in the similar manner as Popper/Guslinde – the first, preaching the forced conversion and the imposition of industrial rationality; the second, adept at a less radical position, searching for some understanding with the natives. This does not mean, however, that the novel is based on manicheistic oppositions; apart from the secondary characters contributed with some nuances to the question (as Sergio Manuel, the helicopter pilot, or Vali, a native of Patntrm tribe) the position of the two main characters is far from solid. An initiatory path is imposed on those two Catholic priests, a way that the reader follows anxiously, though that's not to say that the Connell’s novel is a kind of conventional thriller in the same pattern as The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan. It is a narrative much more complex, which approximates the Hades of Dantesque feature to the eastern Buddhist hells, the prose of gothic horror to the criticism of the Nature and Culture destruction by the illicit interests, the ethnographic poetry of oral indigenous people to the visions about the infernal gears of Natural World worthy of the Fitzcarraldo, the Werner Herzog movie. The unique structure of the Connell's fiction comes in a flash on the first page of the novel, when Don Ramiro notes terrified “that vast expanse of green, deceptively beautiful, without any signs of highways, housing or civilization – instead a flowing sea of hypnotic violence." Cannibals of West Papua is a sequel of a previous novel, involving one of the protagonists (Fr. Massimo Tetrazzini), The Translation of Father Torturo (Prime Books, 2005). However, despite this relationship of continuity, clear at times in passages related to the past of Fr. Massimo, the new novel works very well alone. With the focus on the enhancing a wide evocative universe that goes far beyond the West Papua, Connell elegantly avoids the pitfalls of novels serialization. Such elegance is expressed in every detail of the novel, from the language to the creation of a timeless atmosphere, despite all the signs of modernity that appear particularly in the novel's introductory four chapters. After the discovery of the isolated and aggressive tribe of Up-Rivers in the chapter V, the plot leaves any strictly realistic or casuistry restriction to plunge into a chaotic universe full of violence and supernatural (a exquisitely and unique supernatural proposition, in fact), although without losing the subtlety and the systematic development of the narrative structures. As in The Day of Creation or The Crystal World, both by J, G. Ballard, Connell's novel is crisscrossed by two conflicting principles: the reversal and the hybridization tendencies. The central characters, in their successive and agonizing metamorphoses, put both principles in collision and conflict. Not coincidentally, the tradition (in pictorial or narrative terms) enshrines these two foundation concepts to the characterization of hell and thanks to the old and new potentates of the Earth (which are the subject of the author's disgust and anger in the epigraph that opened the book) our planet acquires the features of a continuous and exquisitely Hades, bureaucratized and inescapable, as described in detail by the Connell’s sulphureous prose. The book as an object, produced by Jonas Ploeger of Zagava Press, is intensely beautiful. There are two editions with covers based in the random and unique patterns of leaves – one of this editions with only 26 copies in leather. These patterns suggest, both in visual and tactile terms, a dense, mysterious rainforest. It is impossible not to continuously contemplate, in the reading intervals, this strange and beautiful cover, in search of some hypnotic revelation. Each edition is signed by the author and, although there is no illustrations – just an amazing mask appears in the first pages of the book – the general layout and the paper have a perfect balance, which greatly facilitates the reading. A simple and competent editorial jewelry, the perfect way for a novel that affects the reader, as described by Kafka, like an ax blow. This review was accomplished support from PNAP-R program, at the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional (FBN).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed