|

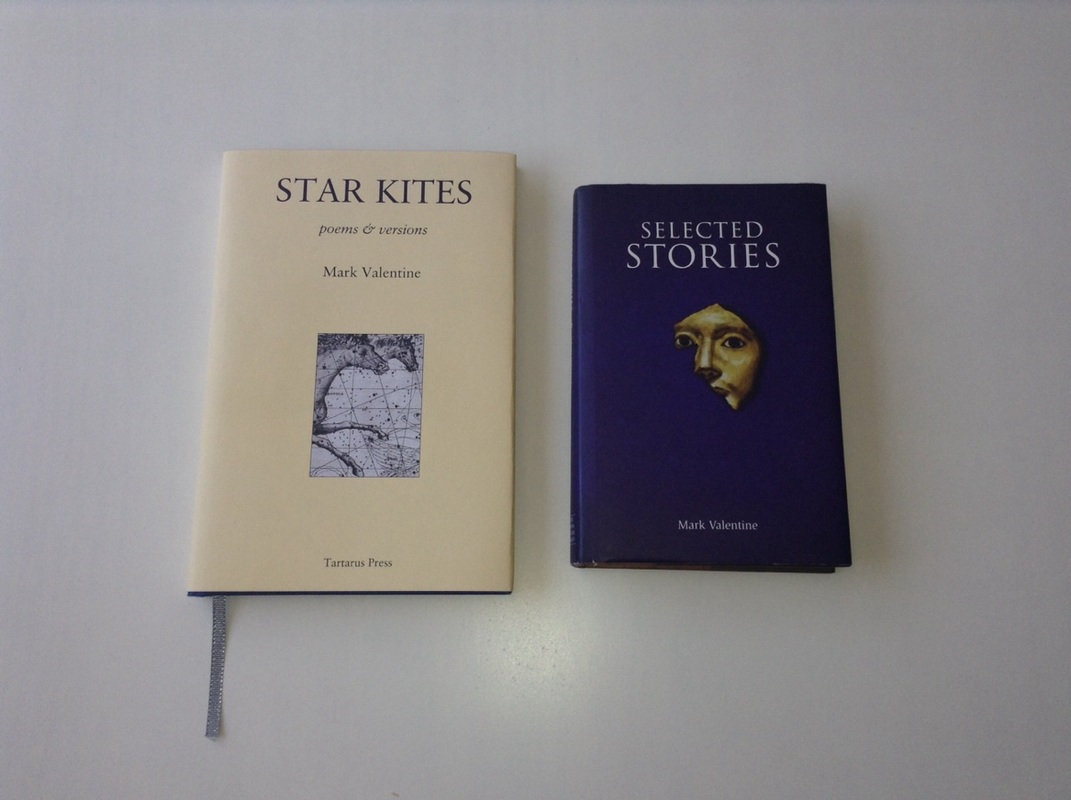

Mark Valentine is a remarkable author who works the contemporary tradition of a kind fiction whose name is legion – fantastic, imaginative, visionary, weird, strange, uncanny, supernatural and so on. He is also had biographical works about important contemporary writers of imaginative fiction (Arthur Machen and Sarban), a scholar of the fantastic genre at the magazine Wormwood and blog Wormwoodiana. Valentine built a fictional universe full of details, filigree and subtle shifts of everyday reality in books like Secret Europe (with John Howard), At Dusk (both by Ex Occidente Press) and Seventeen Stories (Swan River Press). It is not absurd to say that this elegant fiction would be dredged by the attraction power of poetry, and it is possible to see in one of his latest books, Star Kites (Tartarus Press).

One of your latest books is a volume of poetry, Star Kites. The poems presented in the book have a tendency to disintegration of elements on the perception of reality – objects, shapes, even raw materials like marble – seemingly simple but impenetrable (as in the poem with the so suggestive title, "Marble"). This effect was obtained without tricks like objets trouvé or another surrealist intervention. Moreover, this work with the object seems inscrutable feed your creation as a writer. Could you talk a little about your relationship with this usual object, with the same matter, which suddenly turns into a fantastic element, unstable and unpredictable. In my childhood, toy marbles were usually not made of marble, but of glass: real marbles were very highly regarded. Nevertheless, though of glass, they were still shining talismans. In the poem “Marbles”, I try to evoke what these “little beautiful lost planets” meant to me as a first sign of wonder. The swirls in the marbles were mysterious: their colours were a delight. The game involved, of course, rolling these precious spheres along the gutter, to try to strike against your rival’s marble, which meant you won it from them. So there was always an edge of peril and a chance of plunder: you might at any moment lose your own favourite or gain another. And there were other risks: your marble might, as it rolled, disappear down a drain forever. So to this boy’s mind, beauty and wonder were also fraught with fragility and loss. But that did not stop the game, any more than we, mirrors of wonder, can avoid the dust. There is a noted quote by Arthur Machen to the effect that we are made for wonder, for the contemplation of wonder, and it is only taken from us by our own frantic folly. He also noted that “All the wonders lie within a stone’s throw of King’s Cross”, a busy railway station. He did not mean, of course, there was anything special about this area of London: he meant that “all the wonders” may be found anywhere. And so I have found: when we take the chance to stop and look, then a stone, a leaf, a shadow, rust, moss, rainwater, can seem to us strange and beautiful. There are also moments, rare enough, where what we see seems to tremble on the edge of becoming something else: as Pessoa said, “everything is something else besides”. I try in my writing to suggest these things, as best as I can. In the second part of Star Kites there is a work of recovery, and reconstruction, of the poetry traditions (and the poets as well, in the verge of the narrative representing some kind of authentic seer or metaphysical witness in the World) represented by a sort of opaque language (Esperanto to Portuguese, represented by two great authors of modernity in Portuguese, Fernando Pessoa and Florbela Espanca) and style (Ernst Stadler, known as German Expressionism prototype recovered in its most symbolic and mystical) to the point of view of usual reader. Not exactly a translation, but a task of essential and singular visions recovery of these authors, expressed in the poems. Thus, this part of Star Kites brought to mind the stories about poets of your At Dusk. Was there really a relationship, a joint project between the two books? As observation or curiosity, I add that "The Ka of Astarakahn" was one of the best stories I've read in 2012. Yes, both At Dusk and the versions in Star Kites come from the same inspiration, the modernist poetry of the first half of the 20th century. I think that even the most canonical figures in this field can be too little-known amongst English-speaking readers. Those who are further out, on the horizons, are even less known, and yet there is so much to discover here, so much subtle, strange, visionary work. I wrote the versions in Star Kites first, as a way of getting to know the work better: the act of translation is also an act of homage and respect. I am sure that other, better, versions than mine could be made, but quite a few of these poems had never been translated at all, so at least I have made a start. Then, after these, At Dusk is an experiment in a new form. Most of the passages mingle my own phrases, attempted epitomies of the poets, with allusive (rather than direct) quotations. This was an attempt to try something different in the way of "translation" in the broadest sense - the next step further on from the idea of "versions". As with the selections in Star Kites, I chose poets both from the acknowledged canon of modernist poetry and from further out: lesser known poets and lesser known languages. Many of those I chose were cosmopolitan in outlook, using several languages, and choosing (or being forced into) exile: their very lives and work question the validity of nationalism. The modernist poet has no nation but the library, and no language except the images of the spirit, glimpsed. Another front of your fictional creations was, apparently, the empire's twilight: there is in many of his narratives attempting to retrieve a particular universe, these crepuscular atmosphere of empires in the early twentieth century, notably the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Tales like "The Dawn at Tzern", for example, capture something of the atmosphere of this fascinating historical moment on the edge of the World War catastrophe, orderly and traditional, but carrying unthinkable chaos in its structure. Tell me a bit about your job in recreating this historic moment, if would be some consult to historians texts, for example (or, if it is the case, movies, photos, etc.) essential in recreating that subtle feeling. There has been a tendency for history to be viewed from the centre, the capital. In “The Dawn at Tzern”, I asked myself how the news of the death of the very long-lived Emperor of Austria-Hungary would be received further out, on the edges of the Empire, in some remote village. I wondered both how the news would reach the village and what effect it would have. The story tries to explore this through several characters: the diligent postmaster, the radical cobbler, an exiled priest (for what other sort would be sent here?), and soldiers in retreat from the war. The visionary youth Mishael is a shadow thrown by one of the three Jewish youths condemned by Nebuchanezzar to the fiery furnace, who came out unscathed, due to angelic protection. He is still safeguarded, but he remembers his protector in a changed way, as a form from Jewish folklore, a strange great bird. The story tries to convey the different ways open to the dying empire; duty, faith, magic, revolution, retreat. The details are mostly imagined, but it has a little of the influence of Bruno Schulz's story "Spring" and Herman Hesse's novel "Demian". Of course, I do not say it aspires to these. In the previous questions I mentioned historical issues about universes and unique traditions rebuild or evocation, in fact, this is an important facet in your work as a whole, I think. In this sense, your work as a biographer (of authors such as Arthur Machen and Sarban) and as an editor and critic (in the journal Wormwood) would be directly related, would impact their sphere of fictional production or the reverse would be correct? Yes, I was once asked why I devoted time to forgotten authors when I might be writing fiction instead. The answer is that the two fields often work well together. For example, my story “The 1909 Proserpine Prize” imagines a strange episode in the judging of an Edwardian literary prize for dark fiction, partly inspired by my reading of such work. Also, I like to write pieces where the line between story and essay is not always clear. “White Pages” seems to be about a series of authentic Edwardian novelty books issued by a certain publisher, which were mostly ways of making books of blank pages seem more interesting and exciting. Almost everything in the piece is factual, drawing on my research here, but there is a slight turn towards the end which changes the essay into a story. I may also add that when I am writing about a lost or forgotten author, and dwelling upon their life and work, it often seems that some unseen presence or semblance of the author is about, as if they are keen to see their story is told. There is a type of character that you worked a few times: the detective in themes about the occult and the supernatural (for example, Ralph Tyler and the Connoisseur, in collaboration with John Howard). However, your narratives constructed around these character types retain the visions and obsessions that could be found in many of his plots and poems. Apart from the obvious references and tributes, which would be more around these occult detectives peculiar that you invented? Are the narratives based in some historical events, facts and people? The Ralph Tyler stories, which were mostly written in the Nineteen Eighties, are usually set in my home county of Northamptonshire, an unregarded area, essentially a crossing place. They sometimes draw on authentic local history and folklore, but more often the inspiration is the landscape. It has rightly been noticed that this country reveals its mysteries more to the dweller than the visitor: for on the surface it seems pleasant but unremarkable. When I grew up there I would often walk or cycle along lonely lanes to remote villages, and I hope some of my sense of this “lost domain” might have found its way into the stories. The Connoisseur stories, by contrast, often have beneath them the idea that certain properties may be found in art or craft that will offer us a hint of the numinous or magical, and that these may be found at times in everyday objects too. The effect of sunlight or shadow can transform how we see a piece, and I sometimes wonder if there are other transformations possible too, either in how we see, or in how something is. A famous partnership in crime fiction (and film as well) was that of french authors Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, creators of plots that gave rise to such films as Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958) and Henri-Georges Clouzot Les diaboliques (1955). The partnership between of the two authors worked as follows: Boileau came with the plots and Narcejac, atmosphere and characterization. In the case of The Connoisseur, I believe that the way to creating was another, was not? How did working in partnership with John Howard? The first volume of Connoisseur stories, In Violet Veils, was written alone. In the second volume, Masques & Citadels, there were two of the stories, one about interwar Romania and the other about the first crossing of Spitsbergen (Svalbard), where I had made a good start but did not see how to go on. John was able to rescue the stories. This worked so well that we shared all subsequent stories in the series, so that John is rightly now a co-creator of the character. We also wrote a shared volume, Secret Europe, set among the cities and remoter places of interwar Europe: however, in this case, the stories were written individually and are simply published together. John has also, of course, published several volumes of his own work, most recently Written in Daylight (The Swan River Press, Dublin), which ought to be read by anyone who enjoys subtle, finely-shaded supernatural fiction. Are you working on some new narrative or project (there are many characters and plots like The Connoisseur or the poets life of At Dusk that would be fantastic in the Movies) at the moment? Talk about some of your future plans. I don’t know very much about film. I have never owned a television and rarely go to the cinema. Among current projects, a few turns of chance have recently led me back to some sound recordings I did in the early Nineteen Eighties. I was much impressed then by the do-it-yourself spirit of new wave: like many others, I published a zine and wrote for others, and issued my own tapes and contributed to others. That restless sense of just getting on and making things, even if you weren’t trained or proficient, has probably been a great influence. Recently, an experimental musician has been working on pieces based on crude reed organ tunes I recorded then: and a field recording I made (with others) of the sea and a lighthouse foghorn in West Cornwall has been broadcast regularly on an online radio station. I’m also started to look at old, time-stained book covers as a form of abstract art: how the chance markings can seem to have mysterious forms. With my wife Jo, under our Valentine & Valentine imprint, we’re also issuing handmade books of pieces that wouldn’t find larger publication: rare lost literature, translations, obscure essays and prose sketches. This interview was conducted with the support of FAPESP, as part of my post-doctoral research.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed