|

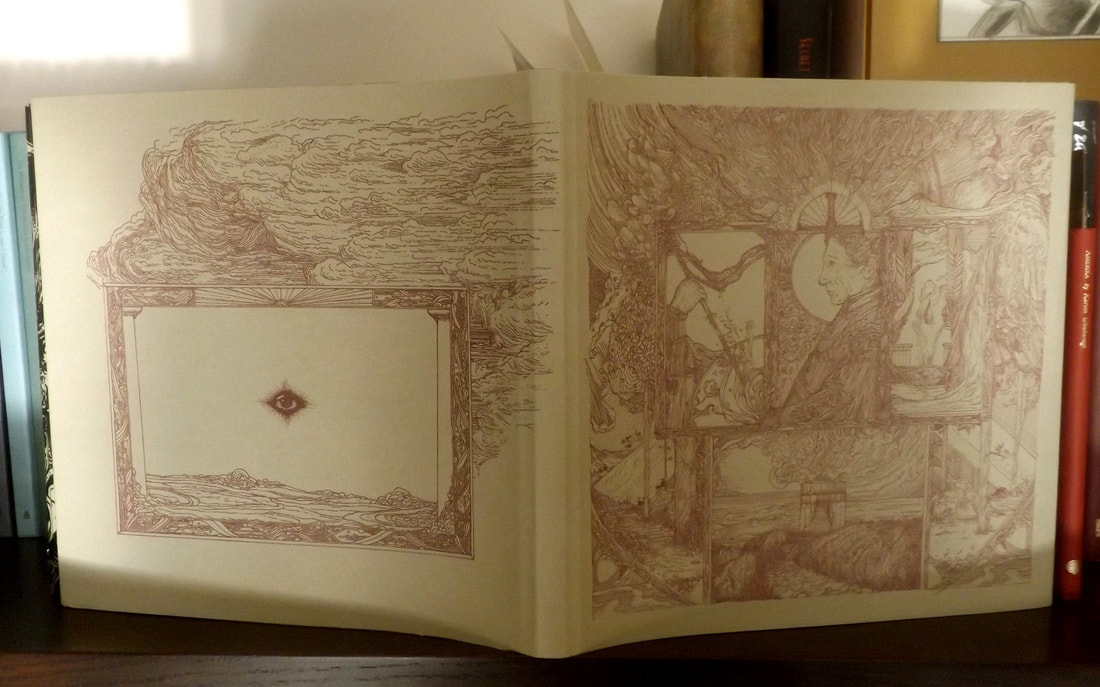

I wonder how the land of Prester John would be in my dreams – perhaps, it would be a territory where milk and honey would flow from the earth. Or, on the contrary, an arid place, in which only the tears would serve to soften the stones. No matter: in my imagination, the possibilities are endless, contradictory, simultaneous. However, this imagined territory needs a map: this map should be a thematic hotel room, in which the borders of Prestes John’s country appear delimited in their physical, political, artistic, and social aspect. In this hotel room, I can begin the unstable rituals for the destruction of this concrete, dull world, which must be gradually replaced by that, wild, that exists only in the impossible continuity of the imagination. Damian Murphy's novels The Academy Outside of Ingolstadt and Abyssinia with its elegant structure, extraordinary images, fascinating characters and situations, not only offers us a remarkable narrative but the powerful resonance of a ritual, unknown and exquisite.Both books deals with geography – an exquisite geoscience, vague, starting from the subjective perception of a seemingly limited space but soon expands to much larger dimensions. The strange locations of both novels becomes, by complex processes of analogy and symbolic perception, in Europe and them, by a new metamorphosis, a scenery that could be, perhaps, our whole universe. In the book books, there are long, ritualistic and initiatory processes, a series of occult, hermetic meanings arise in denser layers. Novels that the spirits of Gustav Meyrink, Bruno Schultz or Franz Kafka would applaud – wherever they may be. Below, two brief interviews with the author about these unique narratives. Photo taken from the Ziesings website. On The Academy Outside of Ingolstadt. 1) What would be the origin of this extraordinary conception of his academy, a teaching institution so peculiar as that outlined in the novel. During the reading, I thought of the many schools, background of so many narratives – for some obscure reason, her academy of Ingolstadt reminded me of the women's school of the book (by Joan Lindsey) and the film (by Peter Weir) Picnic at Hanging Rock. But in any case, your academy has so many unique characteristics that it would be interesting to know the details of its elaboration. There are two teaching institutions described in the book—The Academy and The Institute. Both of these are partly based on my experiences living and working with the administrators of an esoteric order, but also on Gurdjieff’s Fontainebleau Priory and the boy’s academies imagined by William S. Burroughs. The Benjamenta Institute from Robert Walser’s Jakob von Gunten was certainly an influence, as was the Gormenghast of Mervyn Peake. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the school from Picnic at Hanging Rock unconsciously comprised part of The Academy. I’m quite a fan of both the book and the film and am almost kind of surprised that it didn’t occur to me to deliberately include elements from that institution in my own. I can only imagine that it unconsciously influenced the girl’s school described in the red notebook. The spirit of Kafka looms over the text as well, although, as with so many of my influences, the message contained within the book is very much the opposite of that of his work. 2) A visionary aspect is quite evident throughout the structure of his novel. But these are carefully structured visions, perhaps employing some method of conception such as that imagined by William Butler Yeats in his treatise on the subject entitled A Vision. In this sense, talk a little about creating the visions that drive the characters in your book. There’s a very particular mystery at the heart of the story which is never defined directly. It’s indicated in almost every part of the story, including some of the most seemingly trivial details. I don’t know if I could possibly articulate it in a purely rational way—some ideas need to be veiled in order to find expression. It took writing the entire book for me to elaborate it. The structure of the more enigmatic sequences in the narrative refer back to this mystery. This is especially true of the string puppet performance that takes place in the Institute. The vision that unfolds at the beginning of the book arises as a sort of warning for the main character. The second world war approaches, and the character is in very real danger. The Academy seems to stand entirely outside of the shifting tides of European power, and can serve him as a stronghold in which to wait out the coming conflagration. He also needs to return to the school to confront the ordeal that he passed through there in his youth. The school itself, so the impression is given, is endowed with a sort of sentience. If Fräulein Weiss is to be believed, it stands as the repository for the surviving fragments of a lost tradition. It’s reasonable to assume that the intelligence behind the institution remains in contact in some way with its former members. 3) There exists in this book, as in several of your narratives, the book / manuscript found, which structures the vivid unfolding of the plot. But the diary discovered in The Academy Outside of Ingolstadt this scheme is much more complex. From whence came the conception of the red diary and its rich gallery of rituals and characters. Initially, I wanted to explore some of the methods used in the teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff (which themselves provided a certain amount of inspiration for the working methods my own former teacher). Herr Schwarz is almost entirely based on that particular figure. The almost unfathomable depths of Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson, Gurdjieff’s unwieldy masterpiece, provided some inspiration, but only in the most incidental and oblique way. Some of the content in the journal came directly out of dreams. The two schools—the Academy in the main part of the narrative, and the Institute which is described in the journal—mirror and oppose each other in several ways, and are connected by numerous threads that wind their way through both sides of the story. The journal sections contain hidden keys to the non-journal sections, and vice-versa. Of course, an explicit connection between the two organizations is revealed at some point in the book—but then, can Franz be certain that this is genuine? I think it’s made clear that The Academy is not above making use of outright deception, even betrayal, if the administrators think this will further its teachings. There’s a certain amorality at play. 4) The structure of the academy/institute, with its intuitive learning scheme based on the discovery of symbolic elements (the relics) and on growing threats that need a kind of thought that is both elaborate and intuitive. It is a formulation that makes this entity, the academy, extremely alive, throbbing. What is the path to the elaboration of such a pedagogical structure? What is your inspiration in this regard? The escalating severity of the lesson types given in The Academy reflect, on the one hand, the full range of initiatory ordeals presented to the aspirant on the path of occult development, and, on the other, the perilous nature of some of the work undergone at the hands of my teachers. The most profound changes often come about as a result of crisis. This is definitely the case with the main character in the story, in whom a crisis of a somewhat drastic nature is deliberately induced. Photo by Dan Ghetu, at Ex Occidente website. On Abyssinia.

1) At the beginning of the book, there are a reference of three films, obviously fundamental in its composition. In this sense, Abyssinia was thought in cinematographic terms from the scratch – perhaps, as a script for a film, a narrative with visual elements? Is it possible to say that the powerful images that appear in the plot would have originated in this cinematographic sense? The original impetus for the story came not from any of the three films listed at the beginning of the book (Altman’s Three Women, Chabrol’s Les Biches, and Bergman’s Persona), but from the film version of Destroy, She Said by Marguerite Duras. As the narrative developed, the atmosphere gradually drifted more toward that of the three above-mentioned films. I was definitely thinking in terms of the feeling imparted by certain types of cinema when I was writing the book. Often, I’ll watch a single scene from a film over and over again, having become obsessed with the idea of somehow recreating the atmosphere in my writing. In this case, it was more the backdrop for the story, rather than the images themselves, that were inspired in this way. Things like the dream described by Dominik from the balcony of his hotel room, the war stories recounted by Karl Reginald, the images of The Apostate and his wife—these all came from other sources, while the world that they existed in was shaped in accordance with the impressions I received from these films. 2) I think it is curious that in the short list of films mentioned, there is no Last Year at Marienbad (1961), the famous collaboration between Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet. There are some elements in Abyssinia more or less close to the creation of Resnais / Robbe-Grillet, notably the labyrinthine hotel as a backdrop, although with very different results, techniques and narrative strategies. Was such a film an indirect influence, an inspiration by elective affinity to your novel? Last Year at Marienbad is very much a favorite of mine. I’ve seen it so many times that I suspect it casts its shadow over everything I write. 3) There is, in the novel, a fascinating shadowplay between the animate and the inanimate, the active and the inactive, the simulacrum and the real living being. What artifices did you use to create this universe? How did the idea of this dizzying game of projections and mirrors come about? Part of that, especially in the case of doll that Celia manipulates and talks for throughout the story, must have come from the way in which the characters of a story come alive for me in the process of writing. No matter how many times this happens, it surprises me in every instance. The characters of any given piece are at once part of myself and have a life of their own. As they arise, take form, unfold and develop, they tend to take over a portion of my personality. So much so that I’ve actually had to learn how to allow this to happen without letting it affect my outward behavior in inappropriate ways. It’s been said that when an artist reaches a certain level of maturity, they become capable of creating something that’s more than a mere expression of themselves. On the other hand, Jean Cocteau, in his Testament of Orpheus, shows himself attempting to sketch an image of a rose, and instead ends up, to his great frustration, sketching an image of himself. Well, if Jean Cocteau, toward the end of his life, still found himself falling into that trap, I won’t be too hard on myself for succumbing to the same tendency. On the other hand, while everything I write is in a sense a self-portrait, in another sense there’s a different element that arises in the text as well, something that I can’t entirely understand. The same is true with Celia and Karl Reginald—on the one hand, the doll is a projection of something in her personality, part of which is known to her and part of which reveals itself only through his monologues, and yet there’s clearly something else as well. Karl Reginald is at least partly endowed with a life of his own that lies completely outside of his controller. As for how the complex structure within the story was created—I don’t really know how that happens, to be honest. There’s almost always a hidden structure that underlies my stories and which keeps all of the different elements from falling into incoherency. Sometimes this structure is present from the beginning, while at other times, as with Abyssinia, it reveals itself to me a little at a time. Colonel Olcott’s book of maxims reveals the barest outlines of this particular structure, while Karl Reginald’s remembrances (along with several other elements of the narrative) cast it into a different light. Parts of it remain unknown to the reader. I like to think that it can be caught sight of in completion by the intuition alone. 4) In Abyssinia, the reader is constantly placed in a situation in which it is difficult to apprehend the changes in the fluid territory between dream, memory, imagination and perceived reality. This ambivalent atmosphere allows the emergence of characters with powerful symbolic meaning, such as the Apostate – enigmatic, threatening, hieratic. How was the development of this character and the mythic-ritualistic effects in the novel? The figures of The Apostate and his wife made themselves known to me very strongly right at the beginning of the process of writing the story. I didn’t fully understand them until well past the halfway point. By the time I’d finished the piece, I’d written somewhat of a treatise (in my private notes) pertaining to their mythological significance. Still they seem very real to me—they’re larger than life, almost as if I’d encountered them myself in exactly the same way as did Petra. Of course, they’re meant to be personifications of undying principles with which, in very different forms, I have quite a bit of familiarity. Karl Reginald, on the other hand, was loosely (though not too loosely) drawn from a set of real-life experiences. 5) Do you intend, in the future, to resume the fascinating characters and unique universe of Abyssinia? I must say that leaving them behind after the reading experience was somewhat hard. I would be reluctant to return to a character I’ve already created—there are so many new voices that want to have their chance to speak. The feeling of not wanting to let go of a character or set of characters is precisely as intended. Hopefully, they’ll live on in the reader’s mind and continue to reveal things that I would not be capable of revealing myself.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed