|

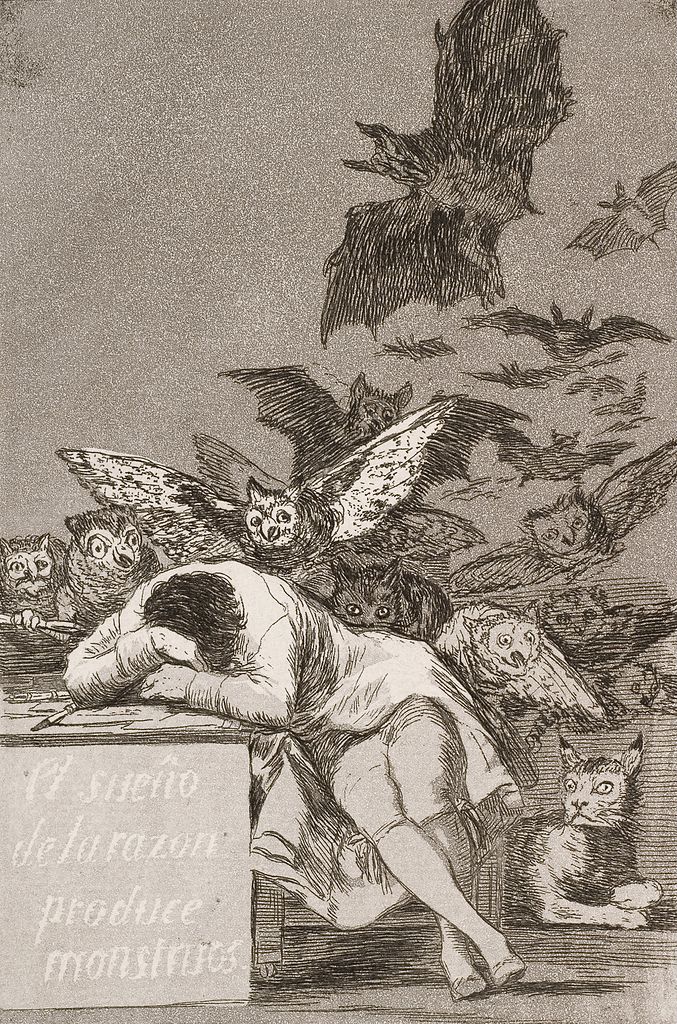

El sueño de la razón, an engraving by Goya. There are some quotes so well known that their interpretation becomes very close to its own formulation – a more or less fixed interpretation, like common sense itself. Thus, the well-known phrase that Goya used in one of his best-known engravings (at No. 43 of Los Caprichos), "The sleep of reason produces monsters", is simply a recognized thought formulaic expression. The speculative dimension is lost, and we have only the premonitory aspects – we need to prevent reason from sleeping, or dreaming, and so we simply avoid the emergence of monsters (in political terms, probably). But if, by a brief speculative (and narrative) exercise, we ignore the prescribed notion of premonition? And if we allowed reason to sleep and dream? A reason with a specific core – historical, social, civilizational. What would happen? What images would the dreams and nightmares of this apparently autonomous reason produce? I believe something very close to that evoked in the fiction of Karim Ghahwagi, especially in this small breviary that is Children of the Crimson Sun, published by Egaeus Press. In the two narratives contained of the book, there is a visible, almost obsessive dedication of history, following the accurate evocation of past events. In the first tale, which borrows title to the book, we have a doctor who tries to help a girl, victim of astonishing ecstatic states. In the second tale, entitled "A Haunting in Miniature," a woman makes an investigation into strange supernatural phantasm in a group of Napoleonic Wars aficionados, making gruesome findings. In both tales, we have powerful historical facts moving to the background, like an amazing shadowplay. In the foreground, there are the so called “minor” events that flow in a dynamic of mutation, change, inconstancy – something that would the happiness of Heraclitus. But these events staged in the limelight are, in turn, petty, seemingly distant from the historical relevance of the great facts and narratives. As in a nightmare, the monster that emerges from the sleep of Historical Reason that is the focus of Karim, we have fragments, daily and prosaic details that are transfigured into a powerful and grim narrative. The logic of mutations in the two tales, thus reveals itself as the threads of a dream, a perpetual dreamlike activity, which our author chooses not to suppress but to elaborate in the most sophisticated way possible. The title story, in fact, made me think of the idea of vicious circle and Pierre Klossowski's strange philosophical novel, The Baphomet, but in a different pitch – very peculiar and far from philosophical experimentation imagined by Klossowski. The edition of Egaeus Press, in turn, is a exquisite beauty object, part of the collection Keynote Editions, with all its gold, its appearance of prayers breviary. A unique book, no doubt. And following an exclusive interview with the author. Regarding the two narratives of the book Children of the Crimson Sun, I realize that both work not so much with the History of great and main events (which nevertheless remains in the two plots as a background phantasmagoria). In both "Children of the Crimson Sun" and "A Haunting in Miniature", we have at the center of the stage the history of minor events, of hidden or secondary traditions, of tragedies whose metaphysical dimension often exceeds the apparently banal limits of the facts narrated. Talk a little about your methodology of approach to History and the story building on that curiously smaller, but not less effective, scale. I think that the protagonists in both novellas, ‘Children of the Crimson Sun’, and ‘A Haunting in Miniature’ are outsiders to some extent, while having certain profound connections to the cultures and traditions in which their stories unfold. Sometimes they are trapped and disadvantaged by the circumstances they find themselves in, other times their distinct perspectives lends them certain advantages – for good or ill. While both stories take place in particular historical settings and milieus, both protagonists often navigate, or mine, and investigate certain spaces or narrative cracks in the status quo of the stories and their settings. I think both Martina Voleron and Izabel Jelinek share certain existential dilemmas too; they both profoundly adhere to the tenets of their situations, and paradoxically also find themselves to be in conflict with them, especially when their intentions are benign, or when they seek to disentangle some mystery, or attain some form of enlightenment, for themselves- or for the communities in which they themselves, are part. I think therefore, that one historical approach, in employing a vast sort of canvas, can also be investigated in miniature, sometimes through a single character, or via the examination of a particular group of individuals, and perhaps from a slightly different perspective, in the hope of attaining some additional clarity in what is often a complex historical or metaphysical dilemma or situation . In the second novella, ‘A Haunting in Miniature,’ the protagonist, a priest of the Moravian Church, is investigating a series of hauntings in a small village in the Czech Republic. The story in part concerns a community of eccentric ‘old –school’ miniature painters and gamers, particularly interested in the Napoleonic period. In a sense they seem to want to sustain a certain coda, or even resurrect notions intimately connected to reenactment – and their art form by extension; this gives rise to all sorts of specters, locally, and perhaps in a wider context. Perhaps looking at something in miniature, as a synecdoche of a larger canvas, might help in certain circumstances; it might also prove entirely myopic for certain psychological reasons etc. I suppose both novellas deal with certain juxtapositions of belief systems, sometimes divorced from the sequential temporality in which they developed, often by the intrusion of the dark fantastic, or all too human agency. The power of the images in the two narratives are impressive. The cave scene in the first one or the presentation of the different types of enthusiasts in Napoleonic wars simulations are extraordinary – so complex that they seem to throw the reader into a kind of interpretative vertigo. How do you build such images; was it a slow, layered process, or did they emerge as ghosts and visions from your mind? Thank you for saying that. I had attempted to write the first novella, ‘Children of the Crimson Sun’, almost ten years ago, and wasn’t able to do it. I tried again about five years later, and found it utterly overwhelming and all but impossible. I cannot entirely remember any longer which images arose at what point, but the first draft of the first half of the story was written while visiting Tripoli, Libya, and I recall writing the story each morning while on holiday and hearing the sound of the call to prayer from a nearby mosque at the time. The latter half of the images in the story are much more recent and have certain connections to a horror story I wrote called Horrill Hill, which appeared in a Cioran anthology, and images in my novella Europa, an homage to William Blake and Mikhail Bulgakov. While I am quite comfortable with the technical aspects of say photography, to understand things like f-stops, shutter speeds, image composition etc, the ‘exposure’ of inner images is an utter mystery to me, and that in part has inspired the writing. Some images are artifacts of gleaned things buried in memory and the subconscious to resurface, some sort of synthesis I suppose, while others simply just seem to make themselves present, and I guess that part of the writing process is also an attempt to understand, or decode some of them. As regards to my approach in the first novella ‘Children of the Crimson Sun’, I spent the formative years of my childhood in Malta. I lived there from the age of six until I was sixteen, often spending summers and some Christmases in Denmark. I grew up surrounded by the buildings and fortifications of the Hospitaller Knights, and I remember visiting a megalithic temple in Tarxien to the south east of the island for the first time, and the caves of Ghar Dalam in Birzebbuga on a school trip when I was about eight or nine. I also remember seeing a recreation of the Great Siege of Malta in a museum-commissioned film, done entirely with silhouettes, fire and dramatic music and narration when I was about ten, that made a significant impression. I attended a private English Catholic all-boy’s school in that period, and had some teachers there who were nuns and priests. Those ancient caves and remaining fragments of megalithic temples, so prevalent on the islands, and the story of the Hospitaller Knights, and the Catholic faith, are certainly elements in the novella ‘Children of the Sun’, that I wanted to explore, and which then inspired further images. Malta is also particularly rich with local ghost stories and legends. It appears to be a kind of nexus, for various reasons. It has been about seventeen years since I was last in Malta, and I had opportunity to visit there again, just before I set to write the later chapters of the novella, but I decided that I wanted to describe any exterior elements of the islands from childhood memory, especially towards the conclusion of the story, in its more fantastical scenes. Also being a life-long miniature painter myself, I do enjoy the painting aspects of the hobby, and had opportunity to then introduce some of those elements into the setting of ‘A Haunting In Miniature’, into a sort of antiquarian ghost story. The novella "Children of the Crimson Sun" seems to have its center of gravity in the notion of mutation. The character's gender shift, for example, between pages 24 and 25, happened so suddenly that, in the eyes of the reader, it emerges at the same time as a rupture and as a possible event in the fluidity of the events of the plot. What was your inspiration for such a complex mutation approach? For nearly a decade I was unaware of the main character’s true nature. It was revealed to me only when it happened in the scene. I had written an earlier draft of the scene, where this moment had not occurred, and then wrote the next three chapters also. Then when I returned to that scene later to expand it, I was completely taken back when it happened - I remember just staring at that sentence with utter surprise, and then a substantial, subsequent section of the story became clearer to me, and allowed me to dare to attempt to finish the story. In retrospect there was already a certain ambiguous fantastical element introduced for the first time into the story in that scene, but then an additional sort of non-fantastical transformation also then occurred, and it then allowed me to understand that the novella was perhaps hovering between these two approaches in many different moments of the story, which I felt were interesting to explore. And certainly, there are other transitions, or mutations, or transformations in the story too, both physical, psychological and spiritual, and eventually even geographical/ architectural. There is certainly a preoccupation with particular religious iconographies, and certain religious tableaus in the Catholic tradition, of both the heavenly and infernal, that form part of the imagery of the story. I think also, that there is a certain ambiguity, in the moments of transformation or inversion, or a wavering, unsettled fluctuation between the one and the other. I had not considered the idea of rupture in the context of transformation or mutation, as a possible event in the fluidity of the plot, but you bringing it up here in context of the moment’s initial creation, or in the moment of mutation, and the effect it had on the rest of the story, is entirely persuasive, and an exiting thought to me. D'vorah's visionary state is quite peculiar: it is a elaborate synesthesia of colors and sounds, which the monks seek to reproduce literally, for the sonorities emitted by the child seem to defy the cognitive limits of consciousness. I wonder what the records of these monks would look like, what each one would contain. What is the immediate inspiration of that visionary state of your novella? I think it was interesting to attempt to map a certain belief system, that then found itself visited by a different sort of transcendent system, glimpsed in the inner eye of the beholder, perhaps spurred by an instigator of ambiguous origin. There is a certain dynamic montage, or polyphony of voices and sources, where perhaps something vaster than the sum of its parts is spurred into some sort of being, whether or not this is divine, or of some other origin, is perhaps part of the frisson of the story. I think that there is a certain ambiguity in the story in the relationship between muse or revelator or augur, and the perception of the receiver. I like the idea of a certain dynamic polyphony that the reader is presented with, an accumulation of glimpses that might draw the reader towards creating his or her own imagery in the mind. There is this notion of a kind of transference, or communicative non-verbal link, spurred by sound and perhaps by other energies, which then transform into certain sequences of words, language, images, architecture- all notions I find to be compulsively interesting to explore. In both novellas I was interested in having images fluctuate between their purely so-called ‘cinematic’ dimensions, and then for other images to function or manifest in a different sort of space. I guess in the story they are both manifested equally in the lexis of language, but then language can serve, or be employed, or have, certain other functions. To clarify this perhaps, I think sometimes of Arthur Danto’s aesthetics theory on the institutionalization of the art object. An object for example, can be so-called raised into the realm of ‘Art’, can be moved or taken from the ‘real world’ and repositioned into the ‘Art world’ because it is surrounded by language, that asserts that it is so. Language has an institutional function, it surrounds, or raises, or argues for placing that object into the ‘Art World’ -a different realm, or it adds a different, additional dimension to that object. You can be entirely critical of this, or find it partly persuasive, but it is interesting to explore in context of belief systems, applied to the understanding of how belief systems propagate, are understood, are psychologically digested, how they flower, and how they decay. As regards to the actual recording of the augur’s ambiguous condition, the manuscripts would not be unlike the illuminated sixteenth century Benedictine texts. Two texts are created on sheets of vellum at dusk and dawn by a rotating group of scribes, and the texts are then assembled into a single volume by Piranelli in the story. Abbot Jaccard believes that in the spirit of the child’s polyphony, the texts could be shuffled indefinitely, and thereby continuously create a sort of dynamic ‘shoal’ of meaning. There are small unresolved enigmas (at least in a linear and obvious way) in the plot of "Children of the Crimson Sun”: the destiny of the child's grandmother, the location of the ancient temples of Malta, etc. Has this non sequitur strategy of plot lines been deliberate, keeping gaps to widen the aura of mystery? Yes I think this deepens the sense of mystery, and also intensifies certain ambiguities which creates further disquiet. In the strands of the story that deal with metaphysical mystery, I like that certain things remain unresolved which the characters grapple with, which further highlights their struggles, navigating in a world where certain forces seem incomprehensible and strange. I think that the absence of both of the child’s mother and grandmother, creates a maternal vacuum, which then Martina is spurred to fulfill, while already navigating the precarious situation of her own identity and gender. I think we find a similar maternal vacuum in 'A Haunting in Miniature', just as the notions of parenthood are absent, missing or distorted. As regards the location of the ancient temples, there is a kind of transformation, or dare I say a transubstantiation from one physical form or realm and to another, bodily or an architectural one, that is not fully resolved. In the story "A Haunting in Miniature", there is the tension of a political commentary crossing, literally, hidden between the lines of the story; for example, when we are introduced to the group of "totalitarians" within the universe of enthusiasts in Napoleonic wars, when we discover the anarchist origin of the protagonist or when we see the strange name of this invisible antagonist (a kind of character that Tennessee Williams would love), “Kasper Von Hauser", so similar to Kaspar Hauser, the “Son of Europe”. How did this underlying comment arise, which seems so appropriate to the present days. The origins of Izabel Jelinek’s Moravian faith in the story reach back to the protests of Jan Hus, a Czech Protestant uprising that predates Martin Luther, both of which are actually predated by the protest of John Wycliff in England. So along one strand she has this anarchist impulse. There is a certain inversion going on, in that while she is a member of the clergy, a rather progressive one in this instance, certainly in the idea of women priests, gender equality, the role of women leaders in society etc, but there is a certain preservation of the status quo inherent in her position too, but she is certainly an anarchistic one. And she seems to equally navigate by empirical facts, as she navigates by indistinct. This is a characteristic that both women share in each novella. To my knowledge, there is no such term as the ‘Totalitarian’ miniature enthusiast in that particular hobby and art form, though its various subdivisions and separations are genuine. I just couldn’t help myself, in context of the other commentary going on in the story. And I like Werner Herzog’s Kasper Hauser film very much, though it’s a very long time since I’ve seen it. And I am a fan of all of Werner Herzog’s work incidentally. The Kasper Hauser connection is an interesting one I had not considered. I don’t recall how I came to the name, except for it to eventually be replaced by a different name. As regards any political commentary, I suppose I find it very difficult to grapple with those forces which attempt to separate us from each other, who wish to put one group of human beings above another, and who will go to great lengths to manufacture reasons for doing so. I think, perhaps naively, that we should certainly devote all resources to solving humanity’s problems all together. I find the idea of a toy, a miniature soldier painted in showy colors transubstantiated into a rather disturbing spectral appearance extraordinary. Has this finding come from any personal experience? Or maybe some specific reference? I think that miniatures have the same sort of disquieting qualities we associate with puppets, mannequins and dolls. They are inanimate objects that have the surface appearance of something living and human. In the case of miniatures, there is this additional intimate relationship to painting. I find that extremely interesting to explore. When I was about twelve I walked in on a group of English miniature enthusiasts, incidentally in Malta, who were playing a Napoleonic miniature wargame, as a demo to a small gathering in a gaming store. They struck me somehow as being ‘additionally’ dedicated gamers, as the prerequisites for playing their version of the wargame was much more time-consuming and financially demanding. All their miniatures were three times the size of regular miniatures, some were custom-cast in iron and lead, and the miniatures were painted in beautiful oils, as opposed to acrylics. There seemed to be a strict adherence to historical accuracy in the particular color and heraldry of the uniforms whenever a member of the public raised the issue. Everything about this group of dedicated men struck me at the time, as ‘next-level,’ and particularly fervent ‘enthusiasts,’ entirely enclosed in their own world. As regards to the second part of the question, about personal experience, that remains unresolved. It stems from a ten year period in Catholic boy’s school, which I have at present not dealt with yet in my writing, but I imagine I will explore further at some point in the future, if I am given the opportunity. Detail from Miracle of Saint Ignatius of Layola, by Peter Paul Reubens, 1620.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed