|

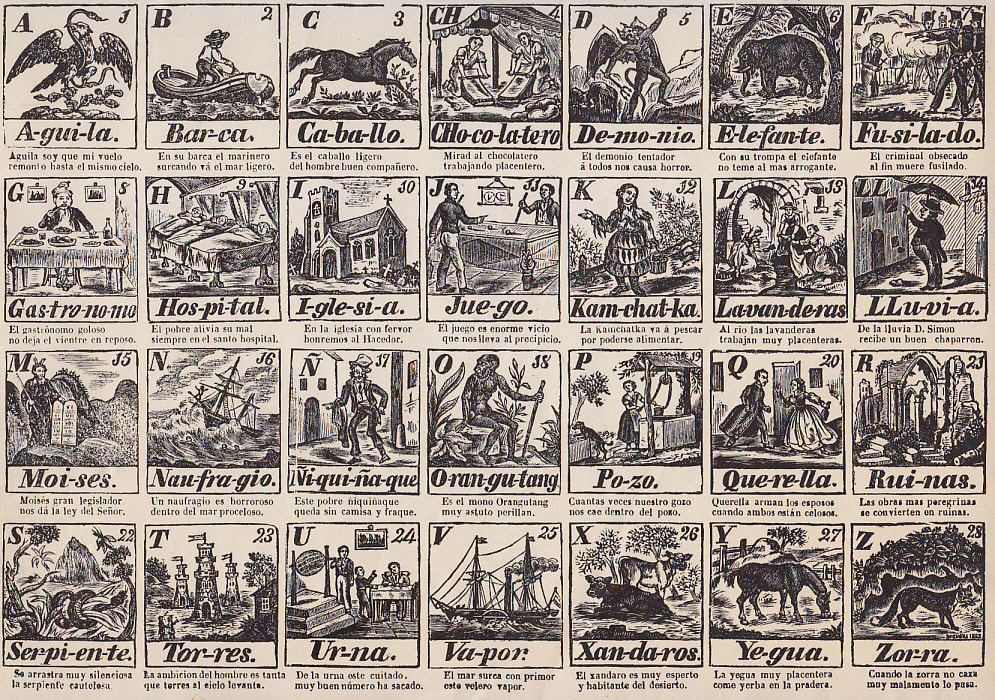

Perhaps one of the most perennial characteristics of Humanity is its tendency to avoid the incongruous, the unknowable. We opted for a easy and crystalline recognition of the objects that surround us – if we are to avoid disturbing experience of the freudian Unheimlich –, with no surprises or shocks. The multiplicity of human ingenuity and art follows the same pattern, and this, of course, includes publishers. The monstrous book is avoided, that is, the volume marked by heterogeneity and hybridity, and this behavior was established in Antiquity, since the privileged target is the harmonic whole, the expected result, the element easily recognizable and catalogable. In his Ars Poetica, Horace reproaches the monstrous book, consisting of unequal and disharmonious parts, stating that such senseless totalities are aegri somnia, these products of unbridled imagination, inaccessible to a conventional, healthy order. Perhaps Horace imagined that these aegri somnia were someday extinct, that the imagination would find a uniform path, that the human mind would conform to the aesthetic projection of the beauty that followed high standards of decorum. But he was wrong: despite all our organization, perhaps even instinctive, of all this pursuit of a purified imaginary, the aegri somnia persist, finding places unusual for its outbreak. Perhaps a worthy heir to this kind of construct that displeased the dignified Horace is, precisely, The Haunting at Tankerton Park, an illustrated book by Reggie Oliver, published with elegant and discreet splendor by the Zagava Press. At first sight, nothing would be unusual in Hauntings: it is an illustrated alphabet, in which each letter is illustrated by a verse and an image simultaneously. Below we have an example of this didactic literary creation (in Spanish) usually intended for kids, taken from the blog El desván del abuelito: In the case of Reggie Oliver's work, the illustrated letters compose a brief narrative, constituted by the act of assembling / disassembling the images and the verses. This is undoubtedly an innovation, although it has even been preceded by some other experiences, such as The Dangerous Alphabet, Neil Gaiman’s creation illustrated by Gris Grimly. However the Hauntings simplicity, austerity, and even conventionality is only apparent: it is a legitimate nightmare, an intricate manifestation in which images, verses and a narrative context become heteroclitical elements of a wholeness that resonates in the mind of the reader and which distances itself from the reassuring references of form or content. In this sense, it is the images that leap into the eyes of the reader immediately; extremely suggestive, they create a veritable grammar of Victorian interiors and atmosphere, including even the orientalist ornaments present in such style, as we see in the letter X of Xerxes. Oliver's drawing style, which he uses in the illustration of his tales, finds here a more subtle and direct expression, in which both the roughness of the woodcut and the softness of the chiaroscuro are emphasized, the transitions between light and shadows, which makes this work close to Goya's etchings. If the book were only these detailed images, these dizzying and suffocating environments in which the impossible, the absurd, occurs, Hauntings would already be a memorable book. But it goes beyond this thanks to two other intricated elements: the verses and the narrative. In the case of the verses, the author sought a certain singleness of the children’s poetry: “F was the Frog they acquired from a farm To eat up the finger that caused such alarm” The simple rhyme evokes the non-sense of childlike rhymes, yet retains the literalness of the element described in the grievous image of the giant toad devouring an equally disproportionate and inhuman finger. This tension between the form (the simple verses), the literalness of meaning and the image that illustrates the verse and that surpasses this seemingly limited functionality creates a remarkable effect. On the other hand, these verses escape the didactic functionality of the syllabary or the illustrated alphabet – Reggie Oliver is not meant to illustrate his reader by memorizing the letters of the alphabet. What he wants is to tell the story of a family moving into a Victorian mansion, finding in this new home the most unusual apparitions. This narrative eagerness disturbs the reader's perception, rendering the experience of this journey through a story with images and verses rather unusual and unique. In fact, the Zagava edition contributes to this, for being exquisite: I have, in my hands, the cheaper version, paperback. Even in its simplest incarnation it strikes from the cover – entirely in black, a negative of one of the many images in the book of Victorian mansions – by size, quality of print and format, makes the revisit of brief narrative a renewed pleasure. And, in fact, this repetition, the act of revisiting, becomes a fundamental pleasure in this brief volume. Walter Benjamin, the German philosopher who worked on such scholarly themes as the German Baroque drama, the narrator (from Nikolai Leskov), the concept of history and the Parisian Arcades, was equally fascinated by the inevitable materiality of the book for children, full of curious and strange idiosyncrasies. For Benjamin the children would materialize a verse from Goethe: “Es ließe sich alles trefflich schlichten, könnte man die Sachen zweimal verrichten.” (Everything would be perfect if one could do things twice). Repetition provides astonishing pleasure for the child; and Hauntings shifts its reader (adult or child) to this dimension of immense pleasure in repetition, to see again those amazing images, to repeat the verses, to remake the course of the narrative. Once again. And again. Note: Goethe's quotation was kindly corrected by Jonas Plöger.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed