|

There are usual, everyday, fortuitous, and familiar narratives, like the family portraits that line the walls of our homes (which we often do not even notice). And there are risky, visionary stories that do not fear crossing borders or following absolutely dangerous paths, which are unviable from the point of view of what is accepted by rationality. In this second case, we undoubtedly find Karim Ghahwagi and his strange travel books Amerika and Europa, systematic descriptions of the new continents of madness. In the continental amplitude of the fantastic narratives, 'Weird', Karim's fictions occupy an original place, between political satire and surrealistic fantasy, between decaying perception and the dynamic record of travels and displacements, between myth and carnival. The author kindly collaborated with the interview we proposed – a first, broader and more systematic part, in writing, accompanied by the second part, intuitive, on video. The two interviews follows below, and I hope both are useful to illuminate the intricate visions of Karim within his multi-layered perspective. Interview with Karim Ghahwagi (Video Version) Interview with Karim Ghahwagi (Written Version)

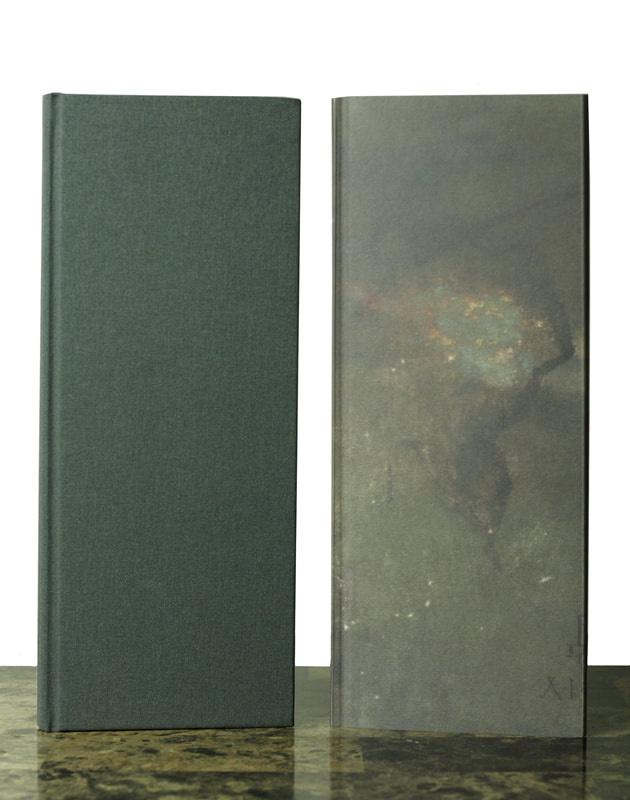

1) The universe of Amerika and Europa novels have a clear resonance of certain works of authors such as Mikhail Bulgakov, William Blake, Emanuel Swedenborg or John Milton (authors, incidentally, cited in these two novels). But there is an evident, very personal development in an absurd, surrealistic and satirical direction which, in addition to revealing a very peculiar verve, also indicates other influences. How did the process of creating these two works take place? What are your main references besides the authors mentioned above? I first encountered Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita while working on my undergraduate literature degree at Bard College in Upstate New York. I was completely derailed by that astonishing book, and ended up writing my literature dissertation on it. I had the great fortune of attending a wonderful class studying Kafka and Bruno Schulz with author Norman Manea, and I was always very interested in the works of the fantastic, the role of the exiled writer, the processes of estrangement, the idea of the writer living far away from his home country. Something that I also encountered in an amazing class reading African short stories with Chinua Achebe. It was however in a class on the literary fantastic, that my professor Lindsay Watton, to whom I dedicated my first published work Amerika, introduced me to Mikhail Bulgakov and Nikolai Gogol. The Master and Margarita completely changed everything for me, but it also encompassed a number of my own preoccupations, and it is certainly a magnificent example of the great polyphonic novel, and the manner in which, as Mikhail Bakhtin writes, it also exemplifies the effects and processes of the carnivalization of literature. These ideas where very important to me, particularly for both Amerika and later, Europa. The carnival could be understood as a celebratory, subversive form of resistance against the absurdity of authoritarian regimes, the idea that laughter and chaos, instigate transformation, remove the tired, malevolent divisions in society, a source of freedom against oppression. William Blake too was against all forms of both social and spiritual repression, and we know that he had an altercation with a drunken soldier in the back garden of his own home and was deeply affected by being falsely accused of sedition; and Mikhail Bulgakov lived through the dark period of Moscow in the 1930’s and forever it seemed, was in Stalin’s shadow (and had personally received a phone call in his home from the man Himself, who can forget). He too never lived to see his great novel published in his lifetime. Both artists in a way were exiled or outsiders, who would only gain increasing recognition after their deaths- though Bulgakov had some success in the theater. In response to your question concerning John Milton, Bulgakov would often refer to his novel in progress as ‘a book about the Devil.’ Certainly Goethe’s Faust was a huge influence, and John Milton’s Satan is very much an anti- hero who never-the-less spurs revolutionary action, an instigator and instrument for change. Woland and his infernal retinue in The Master and Margarita represent those chaotic, whimsical destabilizing forces, demons and clowns, with infernal fractured gazes, causing great de-hierarchizing effects, often confronting and ridiculing and exposing oppressive, unimaginative forces. It is not without reason there is an early central decapitation scene in Bulgakov’s novel, and Blake too was very much affected by the forces of the French Revolution, and how those fires of change swept through Europe and America. In a sense, going back to William Blake, some would identify the beginning of the Romantic period in England all the way back to Blake, a transition, a movement spurred from Goethe to Blake. Literally Katerina Goethe in the beginning of Europa is bringing this revolutionary idea from continental Europe to Albion, as there is a relationship between the sweeping revolutions in America and Europe that Blake was moved by. The idea of confronting the rational, the mathematical, the militaristic, and delving into that deep, internal, mystical well, to put poetry and mysticism, and the whole world in relation to the human. Blake is a true profound mystical humanist. Finally to answer the question of how both Amerika and Europa came to be and their influences. Initially Amerika was submitted as a novelette because Dan Ghetu of Ex Occidente Press had an open call for submissions for an anthology in homage to Mikhail Bulgakov. That ended up becoming its own book, and it was incredibly and lovingly designed by Dan Ghetu. I felt very fortunate to have that work so lavishly presented. In a sort of meta-fictional book about books, where the nature of books themselves are disappearing, or stubbornly reluctant to disappear, it was not without a great amount of joy to seeAmerika published that way. While I had entertained the thought over the years to write a sequel to Amerika, it would be just as comically ludicrous I reckoned, as Mr. Sweden’s supposed sequel to The Master and Margarita as depicted in Amerika. Then when Damian Murphy and Dan Ghetu invited me to submit a short story intended as a panegyric for William Blake, I couldn’t resist drawing parallels both between Mr. Sweden, the Travel Writer in Amerika, and Swedenborg’s effect on William Blake, particularly on The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and his two canonical works, America and Europa. So all this devilry is really Damian Murphy and Dan Ghetu’s fault, for which I am eternally grateful! The thought entertained me to no end however, and what I had intended to be a similar novelette (or novelarette- a term coined by D.F.Lewis), just continued to grow into the short novel that became Europa. I always knew that György Ligeti's opera Le Grand Macabre would inevitably have to figure in the story and was certainly an influence on Europa. All kinds of music and sounds are important to the worlds of both books. The Master and Margarita is an incredibly sonorous and cacophonous novel. I think that the extraordinary work of Brian Evenson had an influence on Amerika, too. I had spent two years adapting The Brotherhood of Mutilation, originally published by Paul Miller’s wonderful Press, Earthling Publications- which is the first half of the astonishing novel Last Days- into a screenplay. Working quite a bit with the dialogue and the world of Last Days had an effect in certain ways in which the Jensens for example, spoke inAmerika, and the manifestation of pitch black comedy in a detective noir setting. Brian Evenson creates an unsettling feeling in his stories that is all but impossible to pin down, and it is completely unique and powerful. His extreme care and awareness of certain rhythms in language, coupled with the profound existential preoccupations and often blackly comic subject matter in these highly compressed, terrifying narratives is really like nothing else I have ever encountered, and utterly astonishing. Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil, and Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comic books, and the work of Clive Barker are certainly all influences too. And I think I have always been amazed by Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy of novellas- particularly the manner in which the detective-writer is confronted with subversive existential and inter-textual conundrums. The extraordinary bodies of work of Ramsey Campbell, Peter Straub, China Mieville, J.G.Ballard and Michael Marshall Smith are certainly all influences. What motivated me to write Amerika was particularly the political realities in Scandinavia and the US after 9-11. The vilification of foreigners and immigrants by right wing elements, the shrill tone of some newspapers in the following years, the constant attacks on the Scandinavian welfare system by greedy and nihilistic corporatist forces. In Europa, I think the absurd rise of Donald Trump, the malevolent, racist rhetoric against the poor, the environment, the huge masses of refugees displaced around the world, the detention centers, the ugly rise of elements of authoritarianism in Europe and America in our present time. 2) There is an extraordinary emphasis in Amerika: the manuscript from an unsolicited (or perhaps impossible) novel that does not burn. It reminded me of certain images of the Renaissance/Baroque era, with the same theme – the book that resists the fire because of the heretical content in its pages. At the same time, this emphasis is associated with the theme of the clandestine manuscript tradition in the Eastern Europe, the concept/ strategy of the samizdat. To compose this moment in your book, what references do you use? How did you imagine this impossible object? The Master and Margarita remained unpublished during Mikhail Bulgkov’s lifetime. He burned an early version of the manuscript fearing persecution for his work. ‘Manuscripts don’t burn’ is much quoted from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel. After the book was burned the first time, he would then go on and work on the novel for the rest of his life until his death in 1940. This quote is a testament to the immortality of ideas, that they will overcome censorship, that ultimately suppression will fail. It is also a statement filled with some irony, for the function of infernal fire in the novel also has particular significance, as does a certain subversive Manichaean world view. The Master does not seek ‘light’ in the novel, he seeks ‘peace’. So there are certain layered complexities and ironies in this much quoted statement. I also found Alcediades, a wonderful and complex relationship to light, and fire and illumination in your excellent collection Lanterns of the Old Night. This collection is filled with illuminating glows, from the moon and magic lanterns, and midnight fires on darkened beaches, and in dreams with vast architectures. Even the process of illumination itself, to reveal, and to literally illustrate a text, has a complicated relationship with that ancient light and fire, reaching all the way back to the Platonic cave of ideas, of light and shadow and reflection... So I think both light and fire, and the meanings of ‘infernal fire’ is a complex one, in both its destructive and Promethian dimensions. After Bulgakov burned an earlier version of the manuscript of the Master and Margarita, he ended up rewriting everything from memory, and it was not uncommon for authors at the time to memorize their work in case they were completely destroyed, or for fear of persecution. The Master and Margarita remained unpublished for decades after Bulgakov’s death and finally appeared in censored form in 1966. I don’t believe that a complete uncensored version appeared in English translation until the late eighties. In totalitarian regimes, ideas that deviate from the political program are obviously deemed taboo, and those images of Nazi book burnings are impossible to forget. In Amerika I like the idea of the book as a fantastical object, that it has a power to not only to shift perspectives, perceptions and thinking, but to also literally, to shift architectures, to transform the very fabric of reality, to open doorways to new experiences and vistas. To have characters literally jump off the page, or to interact with each other from different periods and different universes, is something that gives me much enjoyment, and becomes an exercise to test and see those said works when they are given new vistas and new perspectives in the way they are rearranged. Ultimately they are celebrated. 3) Still about the manuscript impossible to burn: the subject of indestructibility appears in his two books through rather complex approaches. Both the manuscript in Amerika and the bullet-proof mannequin in Europa embody strange drives that are impossible to control or liquidate. What would be the origin of this theme obsessively reimagined in your narratives? Working in the shadow of Nazism, Hans Bellmer created these highly unsettling mannequins, pre-pubescent girls with contorted, disfigured anatomies as a way of addressing the grotesqueries and the destruction of innocence by Nazism. These highly unsettling images were impossible to forget when I first encountered them. I am also fond of the Brothers Quay’s vast, incredible body of stop motion work, and their interpretation particularly, of Bruno Schulz’sThe Street of Crocodiles, which is one of the masterpieces of stop motion cinema, or any cinema, for that matter. There is a tradition that the Brothers Quay- in being successors to the work of Jan Svankmajer- that also in my mind, reaches back to a cinematic and literary tradition of the fantastic in Eastern Europe. The idea of the cinema imbuing inanimate objects with life and animation. There is this interesting transition from the literary fantastic to the cinematic one in this particular, vacuum-like, but highly charged and mystically electrical, stop motion space. In fact in later work, where the Brother’s Quay work with ‘real actors’, the human characters in many instances almost appear to be like mannequins of flesh, directed in these strange austere, fetishized spaces- obsessed with structure and discipline, while seemingly struggling to contain vast inner emotional landscapes. I kind of wanted to play with that, and also have the mannequin take on some of the facsimilied characteristics, or lack thereof, that we encounter in the repetitive, militaristic machine-like, banal consistency of military dictatorships. I also think that individual human beings are reduced to mere numbers in malevolent bureaucracies, and are obviously made to be large, unidentifiable masses, and not treated as individual human beings. I also wanted the mythic fires of Blake’s Golgonooza to spread as kind of infernal, destabilizing carnival-march, an oxymoron perhaps, of mannequins. However these mannequins have momentary notable differences in gender, and they are not always completely indestructible, and do suffer from the wounds of both war and time. It was also important I guess, to have the Supreme Chancellor very much surrounded by a puppet cabinet, quickly exchanged, quickly discarded wax mannequins. I had a whole scene of a puppet show trial in the novel that I removed before publication. These so-called indestructible texts, imbued perhaps with a kind of supernatural resilience, are often then, created by extremely vulnerable individuals, writers surrounded by violence, war, oppression etc. I think there is a relationship there, the idea of a very vulnerable vessel being able to access some power or ability, through the fire of invention, to create something ethereal and powerful, divorced, but intimately still, a profound part of themselves. The text being a document, literally of an indestructible mythic voice of fire. 4) The disappearance of America is one of the central leitmotifs of both Amerika and Europa. It is evident that the allegorical burden of this conception goes beyond the more obvious dimensions. In that sense, you could comment on the origin, development and political and aesthetic sense of this idea of the disappearance of an entire country, and the importance of such a conception in your plots. I think the fantastic often operates in that twilight space, in a moment of transition between light and darkness, where our perception of things become uncertain. Having then, something missing altogether from a reality we are usually familiar with, also operates and creates interesting spaces to explore. Sometimes a mere inversion of things can profoundly shift our understanding of things and form fresh perspectives. Sometimes creating those absurd inversions, from situations that are already absurd, well, both farce and satire inevitably arises, sometimes in a necessarily rather shrill and unpleasant dimension. I think travel is its own country. There is a particular space that you occupy when you are in transition, or know that your time in a particular new space might be finite. I think the manner in which your mind operates might in part, be quite particular to that experience as well. I feel very fortunate to have benefited from the marriage of cultures that have made up my immediate family life and from having lived on three different continents. I think my life has been enriched by the immersion into other cultures in my private, social and professional life. I am grateful for gaining a wider perspective into other cultures and trying to understand better what makes us all human beings, while respecting the deep, historical roots that make cultures unique and wonderfully idiosyncratic. One side to this however, is also identifying which is really your home, where you feel that you are least a stranger- or why you feel particularly, that a particular place is your home. Writing and thinking in different languages I think also affects your thought processes. While I don’t do any translation myself, you do hear from writers that also translate books from other languages, and how the process of translation helps them with their own writing, with how they construct sentences and meaning in their own native tongue. Perhaps then, to attempt to answer your question, a marriage of some of these preoccupations I think form part of the background I guess. I am also suspect of those forces then, that try and separate us from each other, or that absurdly suggest that one group of people from a particular culture is inferior to another, and the great, just as absurd lengths they go to, to forward that agenda. 5) It seems to me that in Europa there is a strong influence of William Blake, of the visions and perplexities and even of the influences of that author, adapted to your style. Has the Blakean universe, in this context, come as a reasonable option because William Blake himself created very complex mythology involving continents, territories, countries? What is the relation of the Blakean visions and of this perception of totalitarian politics in his book? Blake has created a complex mythology, one that develops throughout his life, and was continuing to do so until his death. While Blake loved his homeland, and even envisioned a new sort of central spiritual nexus in England, his Albion, his new city Golgonooza, he was very much au courant with the political and social situations in his country and in the wider world. He was fascinated with the swell and power of ideas traveling across vast distances, literally revolutionary ideas moving on the great currents of history. He may have been disillusioned by some of those outcomes, but he was certainly acutely aware of them, and was moved to address them in his work. Blake is constantly working also with a kind of psychogeography, juxtaposing continents atop of one another, sometimes encompassing the totality of the exterior cosmos inside the body of every human being. It’s a remarkable, sophisticated and humane and mystical gesture. That this is in opposition to banal, totalitarian, jingoistic ideas is without question, and a form of resistance to that sort of thinking. But there is this fascination with juxtaposing the spiritual world, a mythic world, very much onto the physical architecture of the ‘real world’. A spiritual geography, and therefore some of the concerns in Amerika, and certain satires concerning that ‘bewilderment of cartography’, I felt was more than a little interesting when exploring Blake with Bulgakov. 6) It is fascinating the usage, in your two novels, of concepts or even names that, taken from their original context, gain new, unusual possibilities. These new possibilities endow such concepts with a flavorful mystery tone; this is the case of the fifth dimension in Amerika and the idea of Wollstonecraft in Europa. How, during your creative process, does the construction / displacement of meaning happens? I can sometimes get a little obsessed with semiotics, the way in which signs and words operate in relation to each other. I think essays by Roland Barthes, and some of the work of Umberto Eco are operating underneath the surface, in ways, in retrospect that I am still trying to understand myself. I think the idea in Eco’s The Name of the Rose, a book obsessed with texts, both real and imagined, (As in the notion that Aristotle had a Poetics of comedy, and not solely an investigation into classic Greek Tragedy) the idea of the censored forbidden text, etc, all I suppose have fed into this. I am, and am not, always completely aware exactly how this operates. I do not particularly reverse engineer concepts to put them into fiction. While I have an idea where certain things are going, I not plot these stories. I start them and they take me where they lead, and as I make that journey things begin to settle into a kind of structure. I think there is this kind of satire concerning that existential psychogeography in giving characters names of countries and concepts and similarly identifying them as individuals that both identify, and disassociate themselves with their moniker, often with varying results. Entirely displacing meaning from concepts and then re-contextualizing them, particularly to give them a kind of supernatural or occult context is something that is interesting to me in selective instances, I guess. I think it comes from the power of collage, of placing certain concepts and ideas in relation to each other to create new modes of meaning, that perhaps would not otherwise have arisen from them individually. 7) The dystopia in Europa is one of the most accomplished of recent times – humorous in its nonsense, preserving in this sense the satirical sources that are in the foundations of both utopias and dystopias. On the other hand, such dystopia is strongly connected to historical and recent events in an elaborated mixture – such as the image of Sherlock Holmes wearing uniform and armband. In this sense, what are the references and the method used to construct this particular kind of world? Thank you very much for saying that. William Gibson and John Scalzi for example, are always reminding us that science fiction that projects into the future, is really addressing issues in the present. Both incidentally are prolific on Twitter, and how I wish that we could have these two gentlemen, just for a week say, take over the current POTUS Twitter feed- that could just change the world and skew it towards a slightly (substantially) more pleasant and informed direction. In any case, I like the idea of re-contextualizing ideas and notions, and to resurrect and test them in a new context. It is also interesting to note, that in both Blake and Bulgakov, in different ways, are very much addressing the notion of time itself. Blake operates in this vast mythic time, and Bulgakov in a sense skews geographies and time as well. We have scenes of Pontius Pilate and Yeshua in The Master and Margarita happening concurrently with the events in Bulgakov’s present day Moscow. Those are incredible juxtapositions, and they provide all kinds of dynamic and powerful readings. The juxtaposition itself on the surface appears to also be a political act, but it runs deeper into a rather more mystical well, and if we read those sections rather more carefully, there is this cross pollination of subtle images that bleed into each other. It is remarkable and I think this notion of creating overtly political satire is not always that interesting, but on other occasions it certainly feels like it is necessary, particularly in these troubled times.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed