|

If a narrative does not close, if the end is not resolved, reasons, consequences, perpetrators and victims, all these elements remains unclear. Because the narrative needs to be the strict exposure of events within a dynamic structure of cause and effect, a machine of projections similar to a magic lantern – the lack of a solution, obscure or crystal clear, this kind of structural error, this defect perhaps unforgivable before the insoluble. Before the mystery, however, there is still one last breath: the ambiguity. In fact, there are differences between the ambiguity and mystery; in the first case (easily exemplified by the elegant and subtle Henry James's fiction), there is a calculated interpretative sequence before the events resulting in the explanatory polysemy effect about what was said/narrated. The ambiguity allows the reader the pleasure of controlled game, the excitement on the given reality of understanding possibilities whose central elements seem to escape the usual rules of probability and logic. The mystery can not be reduced to a number of possible results, a probabilistic combinatorial form: the mystery reveals the limits of interpretative rationality, the way our consciousness interlinks the facts that result in a narrative. With the mystery, the realm of contingencies was past with it’s certainties and the borders of this obscure gray area, the sacred, is the new and unpredictable territory for the reader’s explorations.

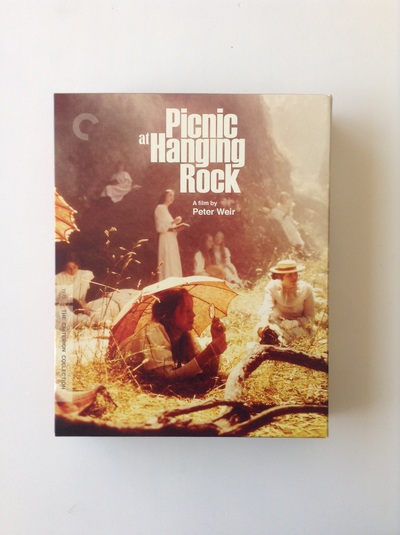

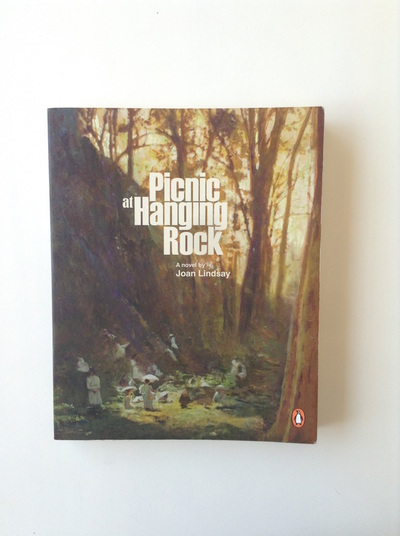

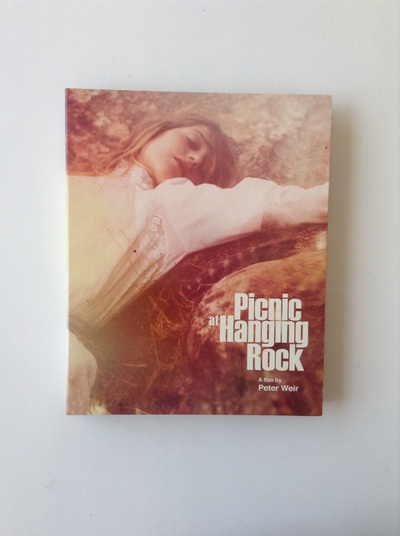

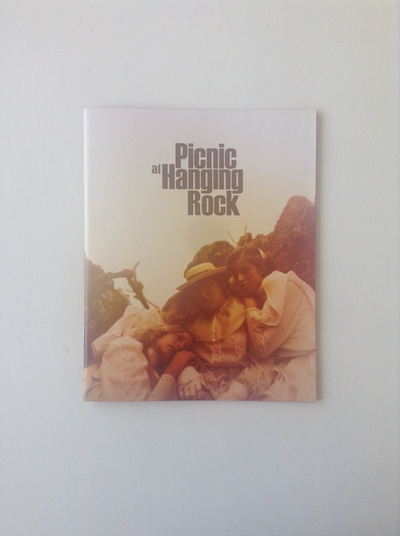

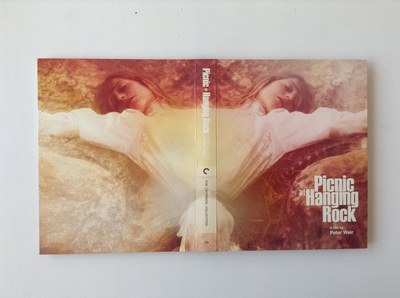

In this sense, it would be possible say that the Joan Lindsay's historical novel Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967) hangs more to the mystery. Written in a particularly rich time of Australian fiction, with powerful developments in the cinema – a few years before, Kenneth Cook launched Wake in Fright, also striking book with an amazing film adaptation – Picnic narrates in its 17 chapters, the events of a unusual day of Saint Valentine in the region of Mount Macedon, where is located the mountain formation known as Hanging Rock, in 1900. In the novel, the students of the a fictional high class boarding school, the Appleyard College, just choose the day of Saint Valentine for a tour – the picnic at the title – in a inhospitable region, close to Hanging Rock. Two teachers head the tour, for better control of the students and to prevent that the open, natural and wild environment does not contaminate in any way the girls. But all this effort was not enough: four brightest students, Miranda, Irma, Marion and Edith, move away from the group toward the Hanging Rock. To this misguided four students joins the math teacher who accompanied the tour, Greta McCraw. All of them disappear without a trace except for Edith, who returns hysterical and amnesic to picnic and Irma later rescued thanks to Michael Fitzhubert efforts, a young man of wealthy family who had an epiphany when contemplating the girls (especially Miranda) in its final upward route. But the other two girls and the math teacher remained missing despite all the searches. As the locals and the police elaborates various explanatory theories, the scandal caused by the mysterious disappearance affects the survivors with the dramatic intensity of the Greek tragedy’s catastrophe unfolding the consequences of the mystery and the inability to understand all it’s branches and clusters. Even after the reader finishes the reading, the mystery seems to linger in its most terrible and irrational sense, so that the very disappearance becomes an opaque event, as the girls and the teacher assumed a role of freewill offerings in a sacrifice. Therefore, a book that appeared in 1987, The Secret of Hanging Rock, with the last chapter and a supposed solution to the mystery, material "discovered" three years after the death of the author for her astute editor, considerably weakens the narrative to offer a solution next to the science fiction. We came to the conclusion that if this "lost chapter" was not pure mystification, some judicious editor acted with considerable efficiency cutting such eighteenth chapter of the final edition. The "alternative" ending published in 1987 makes Lindsay narrative ambiguous, no more mysterious; ambiguity even absorbs the supernatural in its potential possibilities, only providing some central elements of puzzle at it's heart. In the case of the mysterious version of Picnic, we have only specific elements – the date, the weather, the location, the witnesses – irreducible on the possibilities of what actually happened, the disappearance. There are many possible explanatory options: accident, kidnapping, rape, spiritual rising, banal incident; but there isn't any hint to provide advantage to any of these options. The book by Joan Lindsay made considerable success in such a way so that already in 1975 Peter Weir, at the time a promising filmmaker, made the adaptation of the novel to the cinema. The script was done by Cliff Green, a professional writer with several works for television. Weir, meanwhile, made an extraordinary film, the dark comedy The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), a film whose ironic ideas and iconic design influence other motorized dystopias like Mad Max, of his compatriot George Miller. In contrast to the ironic acidity of The Cars, the film translation of Lindsay's novel is subtle: the cinematography seems dominated by faint yellowish tones of sepia, a clear influence of the Australian Impressionism artists as Frederick McCubbin in Russell Boyd’s work as the film cinematographer. Repressed and oblique sexuality appears ubiquitous in this universe of faded colors, which greatly expands its suggestive impact. The school girls emerge as nymphs, appearances of pre-Raphaelite paintings with his long hair and expressions of frozen ecstasy. The ethereal beauty of Anne-Louise Lambeth, in this sense, it is essential for her Miranda personification provides a transcendent and puzzling sense to the perverse games of students and teachers. Thus, the adaptation of Weir has the fidelity to the original story mystery essence, because the film could show more, go further in school details or even make his conundrum explanation, but chose not to do so. The Blu-ray and DVD edition of the film, released by Criterion Films in 2014, seeks to evoke the elusive beauty of Lindsay's prose and the impressionist, ethereal color palette of the Weir film at the same time. For this, first, the movie and book were released in the same case. The brochure and the digipak packaging of each media creates an harmony that works as a complete presentation of the narrative. In this sense, although the edition of the book is simple, there is the beauty of the cover (not a frame of the movie but a Robert Hunt painting) that creates a curious balance for the whole package art (which also includes a booklet with more stills, technical specifications and two essays about the film, written by Megan Abbott and Marek Haltof). Because the typography, visual design and the stills of the film in this edition have dual resonance alluded by the centrality of the Miranda character, which seems to put hypnotically as a kind of events center, even the most inadvertent and incidental facts, an effect that pulses from the narrative of the book to the film. Would Miranda be the focus and the key to the mystery? Wisely, Criterion Picnic at Hanging Rock edition just underlines the question without any formal answer. The mystery is the curse of our logic, the destruction of the basis of our consciousness that is the interpretation of the ordered facts. We tolerate even an interpretation that provides ambiguities or multiple results, but not the unthinkable or the inscrutable. However despite our horror of such uncertainties, the fascination of what we can’t explain is something appealing and effective. Then we started the theories development to fight and reduce the mystery to nothing. But in many cases we have only frustration, so we return to the beginning, to stunned contemplation of the bankruptcy of our explanatory rationality. This cyclical path feeds some extraordinary fictions, and Picnic at Hanging Rock falls into this category.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed