|

Some authors and artists take a curious career risk: instead of the fear created by a eventually insipid production, the problem with this group is the ability to be dredged, summarized and reduced to a single work, generally considered very important in a artistic and/or historical manner. The author destroyed by his masterpiece, which takes revenge on an unknown or unthinkable offense. A exemplary member of this group, we have no doubt, is the author of manga and anime Katsuhiro Otomo, born in 1954 in Miyagi Prefecture. Otomo, still active and productive, seems the author of a single and remarkable work: Akira, the manga/anime (1982 as a print publication; 1988 as a film animation). Although the impact of the original manga, continuously published in the West by influential publishers like Black Horse, was considerable, nothing serves as preparation for the assault on the senses that is the animation of 1988. With the cost of approximately 1.1 billion yen (considered very high at the time and even today, thinking about live action films), Akira broke an old anime tradition: the indiscriminate use of "limited animation" – in which there is overlap and repetition of pieces of scenes and characters – saving time and number of frames and so, money. Every detail of futuristic Tokyo explodes on the screen with excruciating detail, achieved thanks to more than 160,000 animation cells drawn. The epic scope of the multimedia achievements by Akira (a 2000 pages manga with hairline, sharp and hyper-detailed illustrations that turned into an animation that which employed enormous powers and mobilized some majors in Japanese entertainment in its production), there is no doubt, put in the shade Otomo works produced before and after. But this should not be the case for one of the first graphic novels signed by the young Otomo, Domu, published in serial form between 1980 and 1981 and as a graphic novel in 1983.

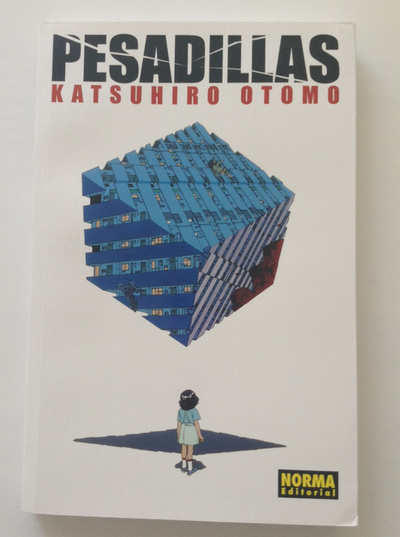

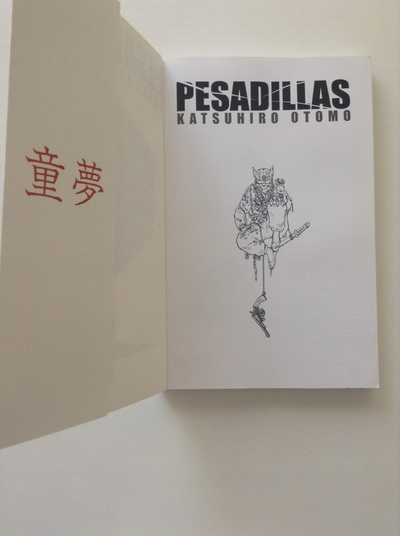

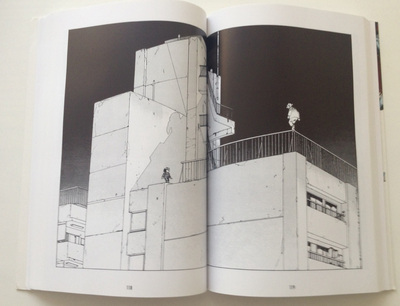

This is only the fifth work by Otomo produced in large scale; still there is a impressive maturity and regularity of the trace in this Baroque and minimalist blending comic, as well as in the plot convoluted and full of quirky characters, placed in the boundary between the surrealist characterization and the brutal caricature of Japanese suburban neighborhood. The plot follows the investigations of a team of police officers who seeks to elucidate suicides and bizarre deaths, all occurring in a titanic housing in the suburbs, the Tsutsumi Housing Complex. Soon the investigators realize that the problem they face is much more complex than imagined: it is a destructive force, perhaps still human not natural anymore. Just like a similar power, in contrast, can solve the problem: the showdown takes mythic proportions, the confrontation between the principle of death/destruction and the life/permanence. The battle between these two impersonal principles obviously results in massive disaster, with terrible consequences for the, police, the building residents and the building itself, this sort of infernal character involving the residents in webs of functional madness. The dizzying plot immerses the reader into the lives of residents, in their cubicles in the a way similar to the destructive power, scanning the most sordid details in a narrative construction not far behind The Invisible Men by H. G. Wells – a considerable achievement for every writer and designer in early career. On the other hand, the plot resembles the first Cronenberg films, especially Shivers (1975), although predate Scanners (1981), at least as a idea. This proximity to the themes and forms of modern fantasy cinema is probably what caught the attention of Guillermo del Toro who tried (unsuccessfully) to bring Domu to the cinema. Domu had good translations in the West: the U.S. (published by Black Horse with the title Domu: A Child's Dream, and currently out of print, with the remained copies negotiated by hundreds of dollars on sites like Amazon or Abebooks) the French (published by Les Associés Humanoïdes titled Dômu: Rêves d'enfants, this edition also out of print) and Spanish (by Norma Editorial, with the title translated to Spanish as Pesadillas, and the only one available for purchase). Of all the issues the Spanish is that I like the most from the first thing: the cover art, though without abandoning certain minimalist and surreal figuration, captures very well the focus of Otomo in the massive public housing as a strange rubik and massive mix between panopticon and gaol. Or hell that unfolds in the very environment that surrounds each character, the most effective of all hells.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Alcebiades DinizArcana Bibliotheca Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed